eBook - ePub

Education and Training for Development in East Asia

The Political Economy of Skill Formation in Newly Industrialised Economies

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Education and Training for Development in East Asia

The Political Economy of Skill Formation in Newly Industrialised Economies

About this book

The East Asian miracle, or its supposed demise, is always news. The Four Tiger economies of Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea have experienced some of the fastest rates of economic growth ever achieved. This book provides the first detailed analysis of the development of education and training systems in Asia, and the relationship with the process of economic growth.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Education and Training for Development in East Asia by David Ashton,Francis Green,Donna James,Johnny Sung in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction and Overview

The remarkable historical episode, in which four impoverished agrarian economies—Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan—were transformed in the space of little more than a generation into industrialised, comparatively affluent enclaves, has provided a spectacle of wonder and evoked enormous intellectual interest. The significance of the East Asian tigers’ performance is not just that they were able to achieve high rates of growth of per capita income, around 6–7 per cent a year, but also that these rates of growth were sustained for something like four decades. Much has been written by way of explanation of this success. Emphasis has been given to the early adoption of an export-oriented strategy for industrialisation, to high savings and investment rates and to a stable macroeconomic environment. Many writers have noted the prominence of state intervention in three of the economies—whether by outright nationalisation of key sectors, or by strongly dirigiste methods of pushing private capital in certain directions.

Reference is frequently also made, however, to the topic of this book, namely the role played by human capital in the growth process. The success in terms of economic growth is paralleled by a substantial growth in skill formation. The Four Tigers already had high levels of school enrolments in 1960, given their relatively low income levels at the time. Participation in first-level schooling, as a proportion of five to fourteen year olds, ranged from 57 per cent to 67 per cent in the Four Tigers (Table 1.1). Other low income countries had much lower participation rates—for example, Pakistan at 22 per cent and Uganda at 32 per cent.

Table 1.1 School enrolment at first level, relative to estimated population aged five to fourteen: selected developing countries, 1960 (unadjusted estimated percentages)

Source: UNESCO, Statistical Yearbook 1963.

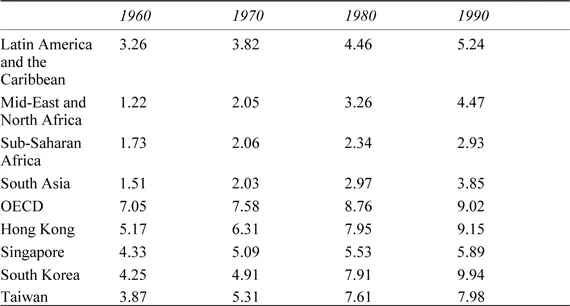

On the basis of the high participation in primary and secondary education the stock of human capital in the tiger economies increased notably in subsequent years. By 1990, the mean years of schooling attained by the adult population exceeded nine years in both Hong Kong and South Korea, putting these two economies on a par with the industrialised countries of the OECD (see Table 1.2). Taiwan was not far behind. In Singapore, human capital measured as schooling attainment also grew, but here less fast. Nevertheless, schooling and higher education in Singapore have rapidly expanded in recent years, to the point where the skills profile of younger workers is similar to that in Northern European countries (Green and Steedman 1997); moreover a very wide expansion of training courses in the 1980s and 1990s was aimed at filling the needs of older workers with less schooling. In other developing countries outside what was the Soviet bloc, while the stock of human capital has increased over the years, it began at a lower level and failed to catch up on the educational lead of the Four Tigers.

Table 1.2 Average years of schooling attained by the population over fifteen years old

Sources: Barro and Lee (1996) and the Barro-Lee human capital dataset at http://www.worldbank.org/html/prdmg/grthweb/growth_t.htm.

This book will assess the question: how are these two growths, that of human capital and that of the economy, articulated? While most commentators have taken the view that the growth of human resources has been instrumental, even vital, for the growth of the economy, there is little understanding of how any causal impact is brought about. The high growth of incomes has itself been an important factor in facilitating increased educational participation. Whether education is viewed as an investment or merely something to be consumed, families with a greater surplus can afford more of it. One can conceive of the two-way chain of causation—education growth to and from economic growth—as constituting a virtuous circle, and see that it was the tigers’ fortune to be placed in that circle, rather than in a stagnant equilibrium of low incomes and little education. A factor commonly recognised as helping to place the tigers in the virtuous circle is their relatively equal societies: this allowed a surplus above basic needs for even the poorest households to devote to education. Yet a danger in viewing the link between economy and skills in terms of virtuous circles is that the processes of growth can appear automatic, and neglect to account for the role of key agents in bringing about change. In the case of the Four Tigers, the central agent for change has been the state.

The importance of the state is partially recognised in those analyses based on conventional neoclassical economics. Because skill formation is subject to substantial externalities, whereby one person’s education benefits others as well, or because the skill formation requires financing in an imperfect capital market to which the poor have restricted access, the state intervenes to rectify such ‘market failures’. The governments of the Four Tigers have been praised for their wise choice of intervention channels, especially their concentration in primary education (World Bank 1993). It is our contention, however, that the state’s part in linking the economy with skill formation extends well beyond the domain of market-failure redemptions, and must be conceived in a new way. That new way is drawn from a combination of the insights of political science, economics and sociology.

The general argument is as follows. A notable body of scholars has attributed the success of the overall developmental catch-up of the tiger economies to the agency of particular forms of developmental state that developed after the Second World War due to specific strategic, political and economic exigencies during the process of state formation.1 These states, through a certain amount of domestic relative autonomy from their respective societies, have to varying extents been able to mediate between the domestic and international economy. They have facilitated movement from the periphery to the semi-periphery of the international economic order by manipulating and creating comparative advantage, using processes such as economic planning and relative control over, or alliances with, industry. While the various mechanisms used to influence the direction and growth of industry and trade have been thoroughly explored, there has been a paucity of investigation of the measures these developmental states have taken to influence skill formation. Our aim is to fill this important gap in knowledge.

In an economy that is being rapidly transformed, a close matching of skills supply to skills demand is hard to conceive in purely market terms. Skills supply is an industry with a very long lead time, with consequent uncertain market signals and sluggish or non-existent responses to market shocks, whether by individuals or firms. A market-led adjustment process is likely to be less efficient than a political adjustment process, if the political leadership has the objective of ensuring skills supply meets the demands of the economy.

We hypothesise that an important characteristic of the developmental states has been their ability to link skill formation policy closely to specific stages of economic development. In brief, developmental states control both the supply of skilled labour to the marketplace, and the demand for skills (to varying degrees) through their industrial and trade policies. They also coordinate the supply and demand at the highest level to fit with the expected trajectory of economic development. Thus, the appropriate mix of skilled labour will be trained for a particular stage of economic growth that has to some extent been predetermined. This model of ‘developmental skill formation’ contrasts with other successful systems of skill formation such as those in Germany and Japan, where the state is not the only dominant agent for change. The result of the state’s coordination in the Four Tigers is that the rapid economic transformation is matched by an equally remarkable transformation in the stock of skills.

These states, however, present different forms of developmental state on a continuum from Hong Kong, which shows minimal intervention in the economy, to Singapore where the state is strongly dirigiste. The institutions, mechanisms, linkages and the actors involved in skill formation policy will therefore differ amongst the four. One might expect to see a less successful match between skills formation and stages of economic growth in Hong Kong than in Singapore. In addition, the developmental state itself is subject to domestic and international economic and political vagaries which will either strengthen or weaken its relative autonomy from society. There are reasons to expect that relative autonomy to be undermined by the very success of economic growth as it brings demands for liberalisation and democratisation of economic and political processes. Therefore, one would expect to see variations in the success of implementation of skill formation policy within one case over time as well as between the cases. In all four cases, however, the pre-eminence of skill formation as an economic tool of the state will result in a better sequencing and linkage between skills supplied to the economy and the skill requirements of industry than that commonly observed in other countries, developed or not.

There is a simple layout to this book. In the next chapter we go through existing theories about the part played by education and training in the growth of the East Asian newly industrialised economies. We argue for a political economy approach and set out the basics of a model of ‘developmental skill formation’, and then describe the methodology we deploy. The four chapters following provide detailed accounts of the development of education and training policy and institutions in the tigers, taking the reader from the period of post-war revival through to the late 1990s. In each case the development of policy is set against the backdrop of the changing economy. Our focus is on the institutional mechanisms that deliver system responsiveness and on the sequencing of policies. These accounts, based on our own new researches, reveal the extent to which it is possible to use the model of developmental skill formation as a way of understanding the agency of the state. In this light we are able to arrive also at an interpretation of current changes and future prospects.

We bring many of the arguments together in Chapter 7 in asking whether indeed there is a ‘Four Tigers’ model of skill formation. We suggest that on the whole the Four Tigers do conform to the framework of a developmental skills formation model. In the cases of Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan, governments have had major influences on the demands for skills at various stages of the economic transformation. We also identify those explicit governmental institutions which were used to construct and sustain the linkages between skill formation policies and economic policies. We examine how these mechanisms were used to assume strong central control over skill supplying institutions, and how that control was utilised to serve the economic objectives. And we show how these mechanisms have resulted in relatively close linkages between the growth stages of economies and the skill formation systems. In the case of Hong Kong, the colonial state had much less influence on the direction of the economy, and the movement into higher value-added industries was market-driven, rather than state-led as in the case of the other three countries. Nonetheless, one can identify important political mechanisms in Hong Kong, starting in the late 1970s, through which the government ensured an increasingly rapid adjustment of skill formation institutions to suit the demands of the changing economy.

The upshot of our detailed argument is that the policy-making and policyeffecting processes central to the model played an important role in sustaining the economic ‘miracles’ of the Four Tigers. This conclusion begs more questions, only some of which can be addressed in this one volume.

First is the question as to whether the developmental skill formation model is still relevant at the end of the 1990s. We identify a number of tensions and contradictions that have arisen in the skill formation system, as these economies have matured. Not least, the economies have become more complex and the state less powerful. Nevertheless, many of the mechanisms and institutions for linking skill formation to the economy remain in place and are likely to retain an important role even though the economies are operating much closer to global technological frontiers. These processes will continue to constitute a comparative advantage in the global economy into the twenty-first century.

Yet it remains true that an adequate skill formation system is no more than a necessary condition for high levels of economic growth. It is not in itself sufficient, and future growth will depend on a successful resolution of other deep-seated problems of maturity, not least the financial crises deriving from the illregulated credit systems. All economies in the region were affected in late 1997 by the loss of market confidence in the financial systems, even though the structural problems underlying the financial crisis differed from country to country. Among the Four Tigers it was primarily in South Korea that major home-grown problems can be identified, in the shape of the increasingly uncontrolled but still protected chaebol. The typical drama of financial crises—secret trips by important officials, personal fortunes wiped out and so on—formed the background to ill-supported proclamations of economic doom or even, absurdly in the case of the Four Tigers, claims that somehow the economic growth of recent decades had been a sham. Nevertheless, if the collective irrationality of financial markets holds up economic growth in the region, this will not be the first time in the world’s economic history.

A second question concerns how far the developmental skill formation model (or part of it) might be applicable in other nation states—whether developed or developing. For most of this book we focus only on the famous Four Tigers. Our arguments directly concern the states in these countries, not East Asia as a whole. However, we conclude in Chapter 8 with a brief coda to the main theme of the book, by examining certain developments relevant to the specific question: can the model of developmental skill formation, evident in varying degrees in the Four Tigers, be applied elsewhere to other developing countries? Two ways of tackling this question are explored. First, we look at some explicit mechanisms through which Singapore’s education and training policy-making framework has been diffused to other countries. Second, we take a brief look at the case of Malaysia, a country of interest because, at least prior to the financial crisis, it had secured high rates of economic growth based on low cost industrialisation, but had yet to make a switch to primarily high value-added industries and services.

2

The Developmental State and the Education and Training System

Introduction: Education, Training and Economic Growth

In this chapter we are concerned with identifying the current state of knowledge on the nature of the relationship between education, training and economic growth, with special reference to the economic development and transformation over recent decades of the Asian newly industrialised economies. There are a number of different theoretical approaches to economic development. While we are not concerned to rehearse the debates about the fundamental correctness of any one theoretical position, we do aim to review how some schools conceptualise the role of education and training. We then set out the basics of a model of the systemic relationship between skill formation and economic development in the context of ‘developmental states’. This model forms the framework for the political-economic analyses elaborated in subsequent chapters.

Education and work-related training are the two principal, though not the only, means whereby an economy’s workforce acquires human capital. For most of this chapter we focus on the question: how do and should states intervene in education and training to produce more human capital? However, in order to set that discussion in context, consider first the question: how does human capital affect economic growth? While most commentators appear to assume that there is a positive relationship between human capital and economic development, what is the evidence?

In recent years there has been real progress in the understanding of how human capital affects economic growth. Traditionally, human capital has been seen mainly as a factor input into the production process, alongside physical capital and land. This framework naturally led economists to attempt to estimate the separate contribution of human capital to national output and, equivalently, the contribution of the growth of human capital to the growth of output—the so-called ‘growth accounting’ approach.1 Using this approach, however, it has been found that human capital’s role in economic growth is not large, and in some cases insignificantly different from zero (Benhabib and Spiegel 1994). In some growth accounting studies, education is assumed to contribute to growth by augmenting the effective size of the labour force. When applied to Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Korea, this method comes up with the estimate that growth in education contributed around one perce...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction and overview

- 2. The developmental state and the education and training system

- 3. Singapore

- 4. South Korea

- 5. Taiwan

- 6. Hong Kong

- 7. Is there a ‘Four Tigers’ model of skill formation?

- 8. On the diffusion of the model

- Appendix: List of authorities consulted

- Glossary of acronyms and abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Name index

- Subject index