![]()

1

Korea

The Divided Peninsula and the Tokdo/Takeshima Dispute

| |

| | | From Yalta Blueprint to San Francisco System 17 | | |

| | | Wartime International Agreements on Territorial Disposition of Japan 17 | | |

| | | The Yalta Blueprint 17 | | |

| | | Potsdam 19 | | |

| | | General Order No. 1 20 | | |

| | | The Moscow Foreign Ministers’ Conference 21 | | |

| | | Establishment of Two Korean Governments 21 | | |

| | | The Korean War 22 | | |

| | | Toward the “Unresolved Problems”: Korea and Takeshima/ Tokdo Disposition in the Japanese Peace Treaty 23 | | |

| | | Early US Studies of Japanese Territorial Disposition 23 | | |

| | | T-Documents, | | |

| | | CAC-Documents, | | |

| | | SWNCC and MacArthur Line | | |

| | | Early Drafts of the Peace Treaty 25 | | |

| | | March 1947 Draft, | | |

| | | August 1947 Draft, | | |

| | | January 1948 Draft | | |

| | | Reopening of Peace Treaty Preparation and Sebald’s Commentary 29 | | |

| | | October 1949 Draft, | | |

| | | November 1949 Draft | | |

| | | Sebald’s Commentary 31 | | |

| | | December 1949 Draft | | |

| | | Dulles and Peace Treaty Drafts 34 | | |

| | | August 1950 Draft, | | |

| | | “Seven Principles,” | | |

| | | March 1951 Draft | | |

| | | British Drafts 39 | | |

| | | US-UK Joint Drafts 40 | | |

| | | May 1951 Draft, | | |

| | | June 1951 Draft | | |

| | | Korea’s Status in the Peace Treaty 42 | | |

| | | The ROK Government’s Request for Modification 43 | | |

| | | The San Francisco Peace Conference 46 | | |

| | | Proclamation of the Rhee Line 46 | | |

| | | After San Francisco 47 | | |

| | | Status of Korea 47 | | |

| | | Takeshima – Resource Development, International Law, Complication of the Problem 48 | | |

| | | Summary 48 | | |

The disposition of Korea in Article 2 (a) of the San Francisco Peace Treaty has two important implications for the “unresolved problems” of contemporary regional international relations. The first is the status, or recipient, of the “Korea” that Japan renounced. Although the Treaty stipulates Japan’s recognition of Korea’s independence, it does not specify to which government or state Korea was renounced. There was then, and is still, no state or country called “Korea,” but two states, the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the south and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the north. Furthermore, neither Korean government was invited to the Peace Conference, and normalization of diplomatic relations between Japan and the two Koreas was left as another “unresolved problem.” Japan and the ROK normalized their diplomatic relations in 1965, but there has still been no such normalization with the DPRK.

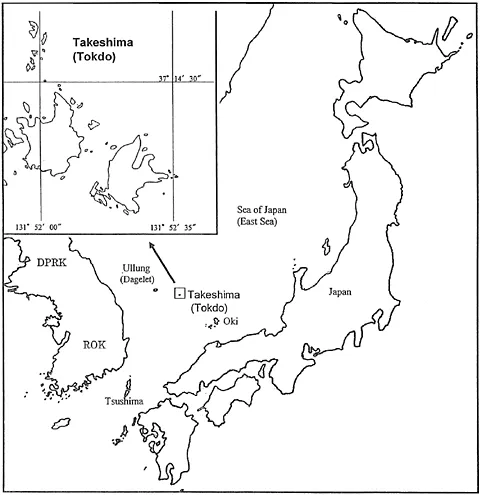

The second respect is the definition of the “Korea” that Japan renounced. This concerns the territorial dispute between Japan and the ROK, the so-called Takeshima (in Japanese) or Tokdo (in Korean) islands sovereignty dispute. (They are also called the Liancourt Rocks in English. The term “Takeshima” is used hereafter solely for convenience.) Even though the Treaty specifies that “Korea” includes Quelpart, Port Hamilton, and Dagelet, it is not clear whether it includes Takeshima.

A great eastern gateway to the Eurasian continent, the Korean Peninsula is 600 miles (966 km) long, with an area of 84,870 sq. miles (221,621 sq. km.), including adjacent islands. The ROK comprises about 45 percent and the DPRK 55 percent of the Peninsula. Its northern land boundaries with China and Russia are marked by the great Yalu and Tumen rivers. Takeshima is off the eastern Korean coast, about 86 miles (140 km) north-west of Okinoshima Island of the Japanese Shimane prefecture, in 37° 14’18”N. latitude, 131° 52’22” E. longitude. It comprises two islets, East and West Takeshima, and some surrounding reefs. Their total land area is 186,121 sq. meters (about one-fourteenth of a sq. mile), and they are currently occupied by the ROK (see Figure 1.1).2

Many studies have been written on post-war Korea and the Korean War, in the context of the global and regional Cold War.3 There are also many Takeshima studies, but under headings such as international law, economic interests, or history going back to ancient times.4 The problems tend to be treated as unrelated, and little attention has been paid to the relationship between them, or with other Asia-Pacific regional conflicts.

Probably because the ROK remains in the Western bloc, most studies of Takeshima limited themselves to the bilateral framework of Japan-ROK relations, and paid little attention to the Cold War context. However, the divided Korea is a problem with an ultimate long-term goal of reunification. The disposition of

Korea was prepared for inclusion in the Japanese Peace Treaty, when North Korea was considered likely to seek reunification by force, as it indeed did in June 1950. Therefore, it can be viewed as a problem between Japan and a “Korea” whose northern half is communist.

This chapter first provides a historical background for the disposition of “Korea” in the Japanese Peace Treaty, particularly the international environment from wartime until the 1951 Peace Conference, paying special attention to US policy. Then, with the disposition of Korea in the Treaty at the center of analysis, issues of (1) the status of Korea, and (2) the Takeshima problem, are examined. Taking the Cold War context of both issues into account, an analysis follows of how these problems emerged, developed in the process of constructing the postwar international political order, and came to be integrated into the regional Cold War structure, or developed into the current status quo.

Much of the background information and material evidence provided in this chapter will also be referred to in later chapters.

From Yalta Blueprint to San Francisco System

Wartime International Agreements on Territorial Disposition of Japan

Japan proclaimed Korea its protectorate in 1905, formally annexed it in 1910, and ruled it until the end of the Second World War. The Japanese Cabinet declared, or “reconfirmed,” Takeshima as part of Japan by the resolution of February 1905.5

Several wartime international agreements covered post-war disposition of the territories formerly under Japanese control. On December 1, 1943 a statement was released following the Cairo Conference of the USA, UK, and China. In accordance with the Atlantic Charter principle of “no territorial expansion,” proclaimed in August 1941 by the Anglo-American leaders, it stipulated that Japan would be expelled from all territories it had taken “by violence and greed.”6 The Cairo Declaration also specifically stated that “in due course Korea shall become free and independent.”7 In defining the terms for Japan’s surrender, the Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945, issued by the USA, UK, and China, later joined by the USSR, provided, “Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine.”8 In the Instrument of Surrender of September 2, 1945 Japan accepted the Cairo and Potsdam terms. There were also important and controversial agreements among the Allied Powers, contained in the Yalta Protocol.

The Yalta Blueprint

In February 1945 the British, US, and Soviet leaders, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin, met at Yalta in Crimea, and the agreements they reached led to the Cold War structure in Europe often being called the “Yalta System.” Germany’s surrender was clearly imminent, so these powers’ major concern was with sustaining their cooperative wartime relations into the post-war era, and clarifying their postwar spheres of influence. The Yalta Conference was marked by their cooperation in constructing the post-war international order. While recognizing the emerging new power balance, and the differences of interests among them, the three leaders nevertheless sought ways to achieve stability of the post-war world and sustain their cooperation.

Their major agenda items were the post-war treatment of Germany and Japan, and formation of the United Nations. Roosevelt made some concessions to the USSR, as he attached importance to Soviet participation in the war against Japan and cooperation in establishing the United Nations. The Soviet Army had already occupied nearly all of Eastern Europe, so it appeared inevitable that the USSR would have predominant influence in Eastern Europe, and therefore pointless to contest it.

During the period of the Nazi-Soviet (“Molotov-Ribbentrop”) Pact (1939–41), the USSR ...