eBook - ePub

Supply Chains, Markets and Power

Managing Buyer and Supplier Power Regimes

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Supply Chains, Markets and Power

Managing Buyer and Supplier Power Regimes

About this book

Supply Chains, Markets and Power takes resource-based thinking forward by stressing the need for a dynamic and entrepreneurial conception of resource acquisition and management. This book will be essential reading for all those with a professional or academic interest in supply chain management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Supply Chains, Markets and Power by Andrew Cox,Paul Ireland,Chris Lonsdale,Joe Sanderson,Glyn Watson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Power in supply chains

and markets

1 Power, rents and critical assets

This book presents a way of thinking about business strategy and operational alignment. It also focuses on what causes firms to be sustainably successful. We will be concerned with three key concepts in our discussion of business success. The first two concepts, power and how rents are earned in markets, should at least be familiar. The concept of critical assets is, however, likely to be completely new to a great many readers. The aim of this chapter is to explore each of these concepts and to demonstrate how they can be drawn together into a coherent and robust theory of business success. This will involve the development of a rigorously defined and empirically testable concept of power in relationships between firms.

We start from the premise that the ideal position for a firm to be in to achieve sustainable business success is one in which it has power over others. By power we mean the ability of a firm (or an entrepreneur) to own and control critical assets in markets and supply chains that allow it to sustain its ability to appropriate and accumulate value for itself by constantly leveraging its customers, competitors and suppliers. We contend that the successful exploitation and protection of these sources of power will enable a firm to be sustainably successful. Success is represented by the firm's ability to earn rents.

The concept of critical assets was first elaborated and discussed in Business Success (Cox 1997). The core argument of that book was that the primary aim of business strategy should be supply innovation leading to the creation of one or more power advantages in order to earn rents. This proposition is based on the idea that, within any supply chain, some of the resources that are used to deliver an end product or service are highly valued in utility terms by a large number of buyers or suppliers and are relatively scarce or unique in ownership, by virtue of being difficult, or sometimes impossible, to copy. It is this combination of high utility and relative scarcity that enables particular supply chain resources to become critical assets both in a buyer—supplier exchange and in a market context. The possession of such critical assets provides the basis by which markets can be closed to competitors and value can be leveraged from customers and suppliers in supply and value chains. The principal aim of this book is to build upon and to empirically test these ideas. Our concern is to understand the major attributes of market closure, and of buyer and supplier power, and to explain the particular supply and value chain circumstances in which we might expect a critical asset to be created.

One of the most original elements of Cox's earlier work (1997) was the contention that business strategy should focus on both supply chains and markets, rather than purely on markets as in more orthodox approaches. See, in particular, the influential works by Michael Porter (1980, 1985). The basic reasoning behind this view is that supply always precedes ‘effective’ demand and that a market cannot logically exist until a firm or an individual has taken an entrepreneurial risk with uncertainty.

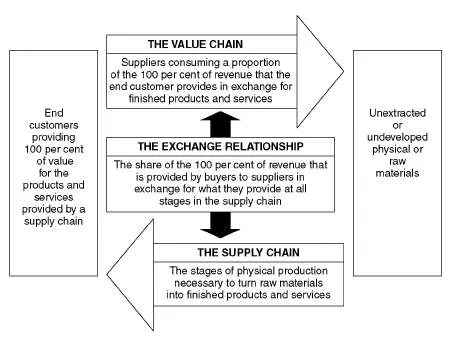

Following this logic forces us to think first and foremost in supply and value chain terms. Supply innovation implies that an entrepreneurial decision to try to fulfil a consumer's unarticulated demand leads to the creation of a supply chain before a value chain or a series of markets, energised by effective demand, has emerged. In short, the activities of a supply innovator bring into being the series of vertical exchange relationships that we call a supply chain. A supply chain is defined here as ‘the series of functional stages that use various resources to transform a raw material into a finished product or service and to deliver this product or service to the ultimate consumer’ (Cox 1997: 211).

This conception of a supply chain is very similar to that employed by the mainstream literatures on logistics, operations management and supply chain management (Houlihan 1984; Farmer and Ploos van Amstel 1991; Christopher 1992; Harland 1996; Saunders 1998). It also corresponds to the concept used by writers concerned with what is known as lean supply (Lamming 1993, 1996). This is where the similarity between this book and these literatures ends, however. All of these writers are interested in the way in which goods and services are physically created and how they flow between firms through a series of interrelated functional stages before delivery to the end customer. Their shared concern is with how these twin processes of product creation and product flow can be managed to achieve greater operational efficiency. The aim is to deliver a better and less costly product to the end customer by integrating and coordinating the physical relationships in the supply chain.

The aim of this book, however, is not simply to examine the supply chain as a physical flow of goods and services. Rather, as we noted above, we are interested in the supply chain as a series of exchange relationships between buyers and suppliers. More specifically, we are interested in how variations in the power balance of these relationships affect the flow of value through the chain.

Where supply innovation stimulates an effective demand, this creates a corresponding value chain in which the exchange of goods and services is mirrored by the exchange of money. This exchange relationship is shown in Figure 1.1. The value chain is thus defined as ‘a series of financial relationships that starts with the ultimate consumer buying the finished product or service and, ultimately, results in all of those who participate in the chain of supply relationships being allocated a share of the revenues flowing from the ultimate consumer’ (Cox 1997: 211).

It should be emphasised that this is a very different way of thinking about the concept of the value chain to that used by Porter (1985). Porter's value chain does not focus on the process of financial exchange between firms, but instead looks at the flow of value between the various functional activities within the firm. He uses the concept in this way because he wants to describe and understand which of these functions add value to the firm's output and which consume value. Porter's concern in doing this is to identify those functions within the firm that are undermining its overall efficiency and should therefore be managed more effectively.

Our conception of the value chain is different, however, because our principal concern is with the distribution of revenues from the ultimate consumer at each of the functional stages in the supply chain. In addition, we are interested in the nature of competition for the revenues at each stage in the chain. This brings us to a consideration of markets. According to the theory of perfect competition, a contested market will emerge where there are opportunities for firms to make profits. Profits are

Figure 1.1 Supply chains and value chains.Source: adapted from Cox (1997: 211).

defined as earnings in excess of a firm's costs of production and they are available when the price commanded by a unit of output is higher than its marginal cost.

This theory also argues that the entry of more and more firms into a profitable market will normally, in the long run, drive the market price down until it reaches an equilibrium with the average cost of production. At this point, supply and demand are in balance and the opportunity to make profits has been dissipated by market competition. Only those firms that are able to break even at this long-run equilibrium price will remain in the market. The fundamental insight of this theory for the present discussion is that, over the long run, profits will tend towards zero, because their existence stimulates increasing levels of competition from new market entrants.

This is an important insight, because it helps us to understand that long-term business success, which is essentially about making money, should not be based primarily upon a strategy that emphasises efficiency and the making of profits. These, as the theory of perfect competition contends, will inevitably lead to the creation of a contested market, which will, in turn, lead to the dissipation of the available profits. This hardly seems like a recipe for long-term business success, but on what alternative basis might strategy be made? The answer put forward in this current volume is that strategy should focus on the acquisition and exploitation of supply chain and market power, and the pursuit of rents.

It is vital, therefore, for us to provide a clear definition of the concept of rents and to clarify how rents differ from profits. Perhaps the easiest way to define rents is to say that they are earnings in excess of the firm's costs of production that are not eroded in the long run by new market entrants. To use the technical economics jargon, rents persist in long-run equilibrium while profits tend towards zero.

The reasons for the existence of rents in a particular market are determined primarily by whether those rents are Ricardian or entrepreneurial. We will discuss the specific features of each of these types of rent later in the chapter. For now it is sufficient to note that both types are a function of the existence of highly valued and relatively scarce resources in a market. Rents will be appropriated by the owners or controllers of these resources as long as their relative scarcity can be maintained. This, in turn, relies on an absence of competition from imitative or substitute resources (Peteraf 1993: 182).

Following this logic, we argue that the basis on which rents are earned is through the possession of what we call critical supply chain assets. Critical assets are based on supply chain resources that can be made relatively scarce, and that allow their owners both to close the market for this particular supply chain resource to other potential competitors, and to effectively leverage value from their downstream customers and upstream suppliers. The relative scarcity of the resources on which such assets are based implies, of course, that only a very small number of firms is likely to have them within any particular supply chain or market at any given time. Thus the appropriation of rents is likely to be a relatively unusual phenomenon. Our conception of business strategy as an entrepreneurial process by which the firm attempts to acquire and control unique and highly valued resources as a means of earning rents places our work broadly within the so-called ‘resource-based’ school of strategy. This school has its foundations in the work of Penrose (1959). More recent contributions include Lippman and Rumelt (1982), Nelson and Winter (1982), Rumelt (1984, 1987), Wernerfelt (1984), Teece (1987), Dierickx and Cool (1989), Barney (1991), Castinias and Helfat (1991), Connor (1991), Mahoney and Pandian (1992), Peteraf (1993), Amit and Schoemaker (1993), Kay (1993), Teece et al. (1997), Galunic and Rodan (1998) and Lieberman and Montgomery (1998).) However, the simple proposition that it is the possession of critical assets in supply chains and markets that enables some firms to earn rents still leaves open the question of precisely how these rents are earned.

The short answer to this question is that the possession of a critical asset gives a firm the potential to achieve relative market closure through a position of dominance over competitors. If this can be achieved, then it is likely that a firm in possession of such a critical asset also has the potential to achieve effective leverage over customers and suppliers in the context of particular supply chain transactions.

We contend that rents are earned through the continuous actualisation of potential supply chain and market power. In other words, a firm earning rents will recognise that it has to focus on both supply chain and market power and will employ that power effectively. The firm will use its market power over weaker and less effective competitors by closing the market to them. It will also use its supply chain power over dependent suppliers to extract cost and quality improvements, while using its power over dependent customers to increase, or at least maintain, its share of the total revenues earned in its market over the business cycle. It is predicted, therefore, that the outcome of an effective use of supply chain and market power will be the appropriation of rents over the longer term.

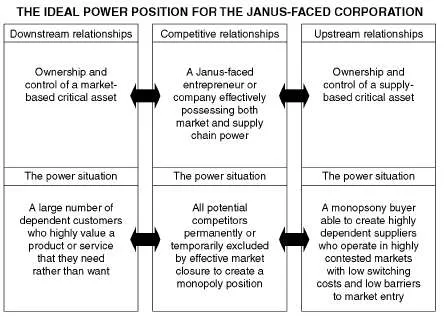

In essence, then, the ideal position for earning rents — or high levels of profit on a sustainable basis — is fairly simple to understand. When an entrepreneur or a company is selling to customers the ideal must always be to have monopoly ownership of inimitable supply chain resources that are needed (not merely wanted) and highly valued by everyone. When an entrepreneur or a company is buying from suppliers, the ideal must always be to be a monopsonist who is able to source from suppliers located in highly contested markets in which there are low switching costs and low barriers to market entry. These ideal business relationships are indicated in Figure 1.2.

We also argue, however, that the majority of critical assets will provide the firm that possesses them with only a temporary opportunity to earn rents.

Figure 1.2 Critical assets and the ideal business situation for the Janus-faced corporation.

This is because other entrepreneurs or entrepreneurial firms will be constantly looking for ways in which the resources underpinning a critical asset can be imitated or substituted. There are essentially three main mechanisms through which firms without critical assets might seek to reconfigure the existing structure of power in any particular market, or supply and value chain. These are product innovation, process innovation and supply chain innovation.

The common focus of all three types of innovation is on the functionality delivered by a supply chain to the ultimate consumer. A supply chain is thus conceived in terms of the need or want that it fulfils, rather than in terms of the concrete products or services that it currently delivers. The aim of a product or process innovator is to satisfy an existing supply functionality by means of a completely new product or process. This is done in an effort to replace the existing critical asset(s) with new assets that are possessed by the innovator. Supply chain innovators take this reconfiguration of power one step further. They do this either by replacing an existing supply chain with a new one that delivers the same functionality, or through the creation of a completely new supply functionality with a new supply chain to deliver those needs or wants. In both cases the ultimate aim is the same, namely to create a new structure of supply chain power, based on new critical assets, that operates in favour of the innovator.

The fundamental point to be made is that those firms that currently have critical assets can never afford to rest on their laurels. Rents are earned not simply from the continuous actualisation of supply chain and market power, but also from an active understanding of how that power might be eroded by other firms through a process of imitation and/or innovation. The potency of most critical assets can be eroded over time, although the extent to which this is possible varies from supply chain to supply chain, depending on the pace of imitation and/or innovation, and from resource type to resource type.

By understanding the threats to its resources, and therefore to its supply chain and market power base, a firm should be able both to defend them and to proactively enhance its dominant position. Conversely, a firm that currently lacks critical assets of its own must constantly look for innovative methods by which it might achieve a more favourable position in an existing or a completely new supply chain. To pursue imitation of those who possess critical assets — which is the dominant strategy of most companies — must be seen as a second-order strategy. The reason for this is that successful imitation normally results only in a highly contested market. Only innovation provides the basis, therefore, for the creation of the critical assets that sustain rents.

This focus on the relationship between innovation, structures of market and supply chain power and the firm's performance (i.e. whether or not it is able to earn rents) forces us to consider where our analysis sits in relation to the insights of industrial economics. In particular, we need to say a few words about the synergy or otherwise between our model and the structure—conduct—performance (SCP) paradigm used by industrial economists.

In simple terms, the SCP model is based on the notion that every firm is embedded within a particular market structure, and that this structure has implications for the firm's behaviour (i.e. conduct) and its performance. As Dobbs (2000: 215) notes, early work done within the SCP paradigm suggested...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Routledge Studies in Business Organizations and Networks

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Notes on authors

- Preface: power and the Janus-faced corporation

- PART I Power in supply chains and markets

- PART II Power regimes in supply and value chains

- PART III A research agenda for analysing business power

- Bibliography

- Index