CHAPTER 1

LEARNING, LEADING AND CHANGE IN HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE

This chapter considers why change has become such an important part of our lives in health and social care and reviews the leadership roles that we all take in initiating and implementing change. Leading is essentially about visualising, understanding and progressing change. Leadership is crucial in contemporary health and social care to inspire people to make changes to improve services.

Staff and service users are acutely aware through their own experience of the speed of change in health and care services. Changing our ways of working usually means that we have to learn to think differently and learn to do things differently. People who understand how to facilitate learning can make an important contribution to change processes. Leaders who understand learning processes can approach change in a way that enables all those involved to learn as they engage in change.

This chapter concludes with a model that sets out the ways in which the book addresses learning, leadership and change in health and social care services.

LIVING WITH CHANGE

We are used to living with change. Change is natural in our universe. It is part of everything in our lives. We are all aware of how our bodies and minds change but, perhaps, less aware of the continuous change in things that change much more slowly, such as rocks, mountains and continents. News media make us all aware of change in the world through reports of natural disasters such as flooding, earthquakes and forest fires. We hear about ecological change including deforestation, climate change causing rising levels of sea water, and threats to our food supplies. We see change around us all the time through the seasons of the year. Even in inner cities we see constant change as communities come and go and buildings and resources are adapted. We also take initiatives to generate change ourselves.

‘Those who believe in the continuity of this industrial age and seek to cling to patterns of work and life as we knew them are not going to license or encourage any exploration of new possibilities. It needs courage to admit that the old must go to give place to the new …’ (Handy, 1985, p. 13) |

Many workers in health and care services are tired of change and feel that they have been worn out by one initiative after another. Sometimes people in public services think that the pressure to change comes from change in government policies. This is true to some extent, but there are pressures that cause politicians to develop these policies. For example, if these services are seen as needing to respond to ever-increasing public demand, the capacity of services must increase and they will cost more to provide, so additional funding must be raised, probably through taxation. An alternative might be to try to reduce demand by educating citizens to take more care of their own health – but then different types of services would be needed to deliver support. As we develop greater technological expertise, different ways of treating illness and improving health become possible. As soon as new treatments and approaches become possible, information travels very fast (often through our improved electronic highways) and members of the public will expect health and care practitioners to know all about the latest methods and to be able to deliver them.

Our health and care services are like ships in a turbulent ocean of ever-changing movements and patterns. The waves on the surface make an immediate impact and we are often forced to change direction or change our speed to reduce the disruption. Storms or a change of climate in a specific location may even cause us to change our minds about where we are going, to choose a different direction. Currents beneath the surface may have a less directly observable impact on our progress but can have a significant impact on speed and direction. Rocks provide obstacles that can endanger us or cause us to change direction or to move carefully through channels that avoid contact. There is risk in most of our progress and, as everyone knows, ocean liners are very slow to stop or turn around. We need to maintain the ship to keep it afloat, to hold on to our sense of direction but also take care to navigate around obstacles and constraints. We also need to take advantage of the flexibility we have in our various situations if we are to adapt quickly enough to respond to changing circumstances. We need leaders to help us to take these initiatives.

WHY ARE LEADERS NEEDED?

Many environmental factors put pressure on organisations to change and we might be tempted to stand back and let whatever will happen just happen. This would be a reactive approach to change, where we formulate a response to each thing that happens, adapting to developments or trying to fix things that have gone wrong. The alternative approach is one of thinking and planning to predict the need to adapt or to try to prevent things from going wrong – a proactive approach. Most of us who care about providing reliable and high-quality services want to do everything possible to make sure that these services are delivered without hitches, so we favour taking a proactive approach. Proactive change in organisations and services has to be initiated and progressed by people. These people are leaders.

Leaders work with others to visualise how change could make an improvement, they create a climate in which the plans for change are developed and widely accepted and they stimulate action to achieve the change. Leaders who can work with others to achieve improvements are needed at all levels of health and care services. Leaders are needed to make the small day-to-day changes that ensure services continue to meet the changing needs of the communities they serve. Leaders are also needed to achieve the more dramatic step changes that have to be accomplished to change the direction or focus of services when new approaches are introduced.

THE EXPERIENCE OF CHANGE

Change is often discussed as though it is something abstract that will affect an organisation or service, but any change in these structures will have a personal impact on the people who work in them or use their services. Health and care services deliver many different types of care to large numbers of people, but in ways that attempt to meet their individual needs. These are personal services and people who use our services often feel frightened and vulnerable. Those who deliver and those who use services engage in them through interpersonal, face-to-face transactions. People learn to do things in particular ways and become accustomed to particular ways of doing things. Change involves doing things in different ways.

Change often requires people to think about things in a different way as well as to do things in a different way. This is one reason why change can be so difficult for individuals, particularly when people are feeling tired or anxious. Instead of going through the motions with familiar roles and activities, change requires an additional effort from us. In order to think and act differently, we have to learn new ways.

Health and care services are experienced in very personal ways both by staff and service users. |

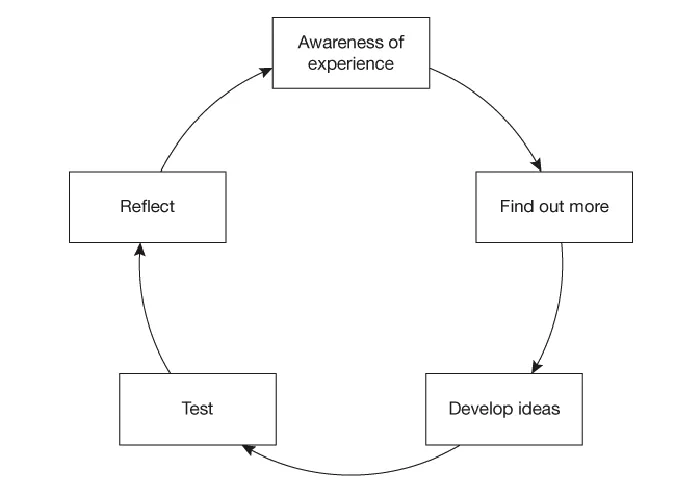

We are often frightened about having to learn and change, which is odd because we all have personal experience of successful dramatic change in our own lives. We all somehow learn to grow from being babies into adults, going through many different stages and somehow accepting that as we grow and change, we develop different views of the world. As adults we all have considerable experience of learning to change, but some of us have learnt to use processes that help us to learn from experience. Many practitioners in health and social care reflect on their experience of practice to help them to learn. Reflective practice is often based on the idea of an experiential learning cycle (see Figure 1.1).

Kolb and Fry (1975) viewed learning as a cyclical process with four key stages: concrete experience, observation and reflection, generalisation and abstract conceptualisation, with a final stage of active

experimentation. In Figure 1.1 these stages have been described more in terms of what a learner does in the process of learning from experience. Kolb and Fry’s final stage has been split into two, ‘taking action’ and ‘reviewing’. The final stage of reviewing includes reflection, which often raises new questions and new ideas that provoke the learner to move once more around the learning cycle, so that it may become a perpetual process.

Stage 1, ‘Awareness of experience’, is the moment at which you realise you are experiencing something you do not fully understand. The learning process progresses to Stage 2, ‘Find out more’, where you look for more information to help you to understand the experience. You might do this by discussing the experience with others, observing others, reading about the issues or reflecting in other ways. When you have gathered enough further information, you are able to form some ideas or an understanding that seems to offer an explanation or a way forward. This is Stage 3, ‘Develop ideas’. At this stage, the ideas are conceptual and so the next stage in the cycle is Stage 4, ‘Test’. This is about trying out your new ideas in practice to see whether they solve the problem or puzzle or offer an explanation that sheds light on the experience. The final stage involves reviewing the extent to which the ideas worked when tried in practice and reflecting on how you might do things differently to achieve better results. This is Stage 5, ‘Reflect’.

This sequence of recognising a concern, exploring and testing ideas and reflecting on what you have learnt can be applied to learning very straightforward things or to projects and investigations that involve much longer learning time-scales. Many practitioners in health and social care use this framework or a similar one in their regular reflection on practice to help them to ensure that they keep learning from their experience and avoid becoming complacent or rigidly repetitive in their practice.

LEADING A LEARNING PROCESS

As learning is so central to being able to change as an individual, an important element of leadership is the ability to facilitate learning. Leaders have their own learning processes and personal experiences of change as well as a potential role in encouraging others to develop understanding of the experiences that change brings.

Sometimes experience of change can be dramatic, even overwhelming, for individuals. Considering experience of this type as a learning process can help individuals to make sense of change for themselves. Although we learn constantly from day-to-day encounters, we are sometimes stunned to discover a completely new way of looking at things. Some call this experience ‘re-framing’, derived from the idea of putting something in a new context or ‘frame of reference’. For example, you might have had the experience of looking through the view-finder of a camera at a landscape but finding that as you move the camera you see elements of the landscape differently each time your focus changes and the boundaries move.

When individuals experience learning that is so significant that it represents a transformation in how they view themselves and their lives, this is ‘transformational learning’. Transformational leadership is about achieving such significant change that situations are transformed and a new (and hopefully better) situation is created. The links between learning and leading change are close when the experience of those involved is considered.

In health and social care services there is wide understanding of reflective practice and experiential learning. This offers fertile ground for considering what type of leadership is appropriate in these interprofessional and interdisciplinary settings where people from disparate backgrounds contribute to service provision. Developing shared understanding and making meaning together are essential activities if learning and knowledge are to be captured and exchanged. There is increasi...