![]()

Part One

Organization and Planning for Marketing

![]()

Chapter 1

One More Time – What is Marketing?

Michael J. Baker

The enigma of marketing is that it is one of man’s oldest activities and yet it is regarded as the most recent of the business disciplines.

Michael J. Baker, Marketing: Theory and Practice, 1st Edn, Macmillan, 1976

Introduction

As a discipline, marketing is in the process of transition from an art which is practised to a profession with strong theoretical foundations. In doing so it is following closely the precedents set by professions such as medicine, architecture and engineering, all of which have also been practised for thousands of years and have built up a wealth of descriptive information concerning the art which has both chronicled and advanced its evolution. At some juncture, however, continued progress demands a transition from description to analysis, such as that initiated by Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of the blood. If marketing is to develop it, too, must make the transition from art to applied science and develop sound theoretical foundations, mastery of which should become an essential qualification for practice.

Adoption of this proposition is as threatening to many of today’s marketers as the establishment of the British Medical Association was to the surgeon-barber. But, today, you would not dream of going to a barber for medical advice.

Of course, first aid will still be practised, books on healthy living will feature on the bestsellers list and harmless potions will be bought over the counter in drug stores and pharmacies. This is an amateur activity akin to much of what passes for marketing in British industry. While there was no threat of the cancer of competition it might have sufficed, but once the Japanese, Germans and others invade your markets you are going to need much stronger medicine if you are to survive. To do so you must have the courage to face up to the reality that aggressive competition can prove fatal, quickly; have the necessary determination to resist rather than succumb, and seek the best possible professional advice and treatment to assist you. Unfortunately, many people are unwilling to face up to reality. Even more unfortunate, many of the best minds and abilities are concentrated on activities which support the essential functions of an economy, by which we all survive, but have come to believe that these can exist by themselves independent of the manufacturing heart. Bankers, financiers, politicians and civil servants all fall into this category. As John Harvey-Jones pointed out so eloquently in the 1986 David Dimbleby lecture, much of our wealth is created by manufacturing industry and much of the output of service industries is dependent upon manufactured products for its continued existence. To assume service industries can replace manufacturing as the heart and engine of economic growth is naive, to say the least.

But merely to increase the size of manufacturing industry will not solve any of our current problems. Indeed, the contraction and decline of our manufacturing industry is not directly attributable to government and the City – it is largely due to the incompetence of industry itself. Those that survive will undoubtedly be the fittest and all will testify to the importance of marketing as an essential requirement for continued success.

However, none of this preamble addresses the central question ‘What is marketing?’ save perhaps to suggest that it is a newly emerging discipline inextricably linked with manufacturing. But this latter link is of extreme importance because in the evangelical excess of its original statement in the early 1960s, marketing and production were caricatured as antithetically opposed to one another. Forty years later most marketers have developed sufficient self-confidence not to feel it necessary to ‘knock’ another function to emphasize the importance and relevance of their own. So, what is marketing?

Marketing is both a managerial orientation – some would claim a business philosophy – and a business function. To understand marketing it is essential to distinguish clearly between the two.

Marketing as a Managerial Orientation

Management … the technique, practice, or science of managing or controlling; the skilful or resourceful use of materials, time, etc.

Collins Concise English Dictionary

Ever since people have lived and worked together in groups there have been managers concerned with solving the central economic problem of maximizing satisfaction through the utilization of scarce resources. If we trace the course of economic development we find that periods of rapid growth have followed changes in the manner in which work is organized, usually accompanied by changes in technology. Thus from simple collecting and nomadic communities we have progressed to hybrid agricultural and collecting communities accompanied by the concept of the division of labour. The division of labour increases output and creates a need for exchange and enhances the standard of living. Improved standards of living result in more people and further increases in output accompanied by simple mechanization which culminates in a breakthrough when the potential of the division of labour is enhanced through task specialization. Task specialization leads to the development of teams of workers and to more sophisticated and efficient mechanical devices and, with the discovery of steam power, results in an industrial revolution. A major feature of our own industrial revolution (and that of most which emulated it in the nineteenth century) is that production becomes increasingly concentrated in areas of natural advantage, that larger production units develop and that specialization increases as the potential for economies of scale and efficiency are exploited.

At least two consequences deserve special mention. First, economic growth fuels itself as improvements in living standards result in population growth which increases demand and lends impetus to increases in output and productivity. Second, concentration and specialization result in producer and consumer becoming increasingly distant from one another (both physically and psychologically) and require the development of new channels of distribution and communication to bridge this gap.

What of the managers responsible for the direction and control of this enormous diversity of human effort? By and large, it seems safe to assume that they were (and are) motivated essentially by (an occasionally enlightened) self-interest. Given the enormity and self-evident nature of unsatisfied demand and the distribution of purchasing power, it is unsurprising that most managers concentrated on making more for less and that to do so they pursued vigorously policies of standardization and mass production. Thus the first half of the twentieth century was characterized in the advanced industrialized economies of the West by mass production and mass consumption – usually described as a production orientation and a consumer society. But changes were occurring in both.

On the supply side the enormous concentration of wealth and power in super-corporations had led to legislation to limit the influence of cartels and monopolies. An obvious consequence of this was to encourage diversification. Second, the accelerating pace of technological and organizational innovation began to catch up with and even overtake the natural growth in demand due to population increases. Faced with stagnant markets and the spectre of price competition, producers sought to stimulate demand through increased selling efforts. To succeed, however, one must be able to offer some tangible benefit which will distinguish one supplier’s product from another’s. If all products are perceived as being the same then price becomes the distinguishing feature and the supplier becomes a price taker, thus having to relinquish the important managerial function of exercising control. Faced with such an impasse the real manager recognizes that salvation (and control) will be achieved through a policy of product differentiation. Preferably this will be achieved through the manufacture of a product which is physically different in some objective way from competitive offerings but, if this is not possible, then subjective benefits must be created through service, advertising and promotional efforts.

With the growth of product differentiation and promotional activity social commentators began to complain about the materialistic nature of society and question its value. Perhaps the earliest manifestation of the consumerist movement of the 1950s and 1960s is to be found in Edwin Chamberlin and Joan Robinson’s articulation of the concept of imperfect competition in the 1930s. Hitherto, economists had argued that economic welfare would be maximized through perfect competition in which supply and demand would be brought into equilibrium through the price mechanism. Clearly, as producers struggled to avoid becoming virtually passive pawns of market forces they declined to accept the ‘rules’ of perfect competition and it was this behaviour which was described by Chamberlin and Robinson under the pejorative title of ‘imperfect’ competition. Shades of the ‘hidden persuaders’ and ‘waste makers’ to come.

The outbreak of war and the reconstruction which followed delayed the first clear statement of the managerial approach which was to displace the production orientation. It was not to be selling and a sales orientation, for these can only be a temporary and transitional strategy in which one buys time in which to disengage from past practices, reform and regroup and then move on to the offensive again. The Americans appreciated this in the 1950s, the West Germans and Japanese in the 1960s, the British, belatedly in the late 1970s (until the mid-1970s nearly all our commercial heroes were sales people, not marketers – hence their problems – Stokes, Bloom, Laker). The real solution is marketing.

Marketing Myopia – A Watershed

If one had to pick a single event which marked the watershed between the production/sales approach to business and the emergence of a marketing orientation then most marketing scholars would probably choose the publication of Theodore Levitt’s article entitled ‘Marketing myopia’ in the July–August 1960 issue of the Harvard Business Review.

Building upon the trenchant statement ‘The history of every dead and dying “growth” industry shows a self-deceiving cycle of bountiful expansion and undetected decay’, Levitt proposed the thesis that declining or defunct industries got into such a state because they were product orientated rather than customer orientated. As a result, the concept of their business was defined too narrowly. Thus the railroads failed to perceive that they were and are in the transportation business, and so allowed new forms of transport to woo their customers away from them. Similarly, the Hollywood movie moguls ignored the threat of television until it was almost too late because they saw themselves as being in the cinema industry rather than the entertainment business.

Levitt proposes four factors which make such a cycle inevitable:

- A belief in growth as a natural consequence of an expanding and increasingly affluent population.

- A belief that there is no competitive substitute for the industry’s major product.

- A pursuit of the economies of scale through mass production in the belief that lower unit cost will automatically lead to higher consumption and bigger overall profits.

- Preoccupation with the potential of research and development (R&D) to the neglect of market needs (i.e. a technology push rather than market pull approach).

Belief number two has never been true but, until very recently, there was good reason to subscribe to the other three propositions. Despite Malthus’s gloomy prognostications in the eighteenth century the world’s population has continued to grow exponentially; most of the world’s most successful corporations see the pursuit of market share as their primary goal, and most radical innovations are the result of basic R&D rather than product engineering to meet consumer needs. Certainly the dead and dying industries which Levitt referred to in his analysis were entitled to consider these three factors as reasonable assumptions on which to develop a strategy.

In this, then, Levitt was anticipating rather than analysing but, in doing so, he was building upon perhaps the most widely known yet most misunderstood theoretical construct in marketing – the concept of the product life cycle (PLC).

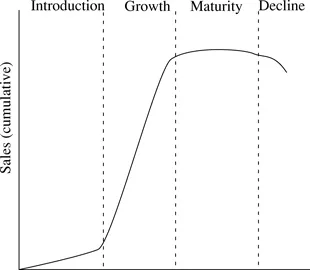

The PLC concept draws an analogy between biological life cycles and the pattern of sales growth exhibited by successful products. In doing so it distinguishes four basic stages in the life of the product: introduction; growth; maturity; and decline (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The product life cycle

Thus at birth or first introduction to the market a new product initially makes slow progress as people have to be made aware of its existence and only the bold and innovative will seek to try it as a substitute for the established product which the new one is seeking to improve on or displace. Clearly, there will be a strong relationship between how much better the new product is, and how easy it is for users to accept this and the speed at which it will be taken up. But, as a generalization, progress is slow.

However, as people take up ...