![]()

1Drones at work and play

1.1Introduction

UAVs, UASs, RPVs—unmanned air vehicles, unmanned aircraft systems, remotely piloted vehicles—are invading the skies. Everyone calls them drones, ignoring the best efforts of political-correctness enforcers to call them something else. Despite the intensity of political debate over them, often focused on trivialities, they are the wave of the future in global aviation. They will not displace manned airplanes and helicopters, because they cannot do the same jobs as well. But they will expand aviation’s capabilities to support human endeavor.

Commercial drone use was already widespread in some parts of the world before the United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) began to relax its ban on commercial flights. In Japan, for example, a medium-size drone, the Yamaha RMAX, is a routine tool for applying chemicals to agricultural crops.1

In the United States, the FAA responded to a statutory mandate to integrate drones into the National Airspace System by releasing a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) in February 2015, allowing commercial activities by microdrones and proposing new rules designed around their capabilities and the risks they present. To relieve pressure for immediate action while the proposed rule was being finalized, the agency granted more than five thousand section 333 exemptions in response to applications by particular operators. Section 333 exemptions—so called because of the statutory section authorizing them—are the regulatory mechanism the FAA uses to permit commercial drone operations pending final adoption of a general rule.

Drones, particularly rotary-wing, multi-copter microdrones, are useful in many applications now. They excel at low-level aerial photography and have demonstrated their ability to collect high-quality aerial news imagery for TV stations and movie production. They operate well in hazardous environments that would present unacceptable risk to aircrews of helicopters and airplanes. Even at the low end of the price range, drones can be programmed to follow search or survey grids precisely. They are regularly used to augment real estate marketing by capturing overhead views of the property and to monitor agricultural crops. Amazon and Google are investing substantial capital in proving drones’ utility for delivering small packages.

The barriers to their wider use are almost entirely political and regulatory, not technological. The FAA cannot quite figure out how to regulate them.

Macrodrones, predominantly fixed wing, with a few helicopter configurations in the early prototype phases, are being introduced into commercial markets more slowly than microdrones, primarily because their size and flight profiles create risks similar to those of airplanes and helicopters, warranting a more rigorous regulatory regime. Their acceptance depends more on their cost competitiveness with helicopters and airplanes than on their ability to perform completely new types of missions.

This chapter explores uses of drones. It distinguishes between microdrones, weighing less than 55 pounds, from macrodrones, those weighing more than 55 pounds. Microdrones have flooded the market already. They are being used for activities where manned helicopters are for the most part infeasible because of cost or risk to aircrews, providing aerial support to economic activities that have not enjoyed it before. In a sense, their missions are being invented, not from past practice with aircraft, but crafted around the capabilities of the new technology—relatively short flights—substantially less than one hour—proximate to the operator—with light payloads, usually a camera. This chapter evaluates the types of missions and the kind of support being provided by hundreds of microdrone flights occurring now.

It also explores possible missions for macrodrones, although this analysis necessarily is more speculative, because few commercial macrodrones are on the market, and the FAA faces much larger challenges in crafting rules for them; their greater weights and more expansive flight envelopes present greater risks.

The chapter begins by reviewing the pattern of section 333 exemptions granted by the FAA. Then it works its way through the types of commercial activities identified by the pattern of the exemptions. After addressing specific sector activities, it explains why the subjects addressed in other chapters of the book enable—and constrain—expanded drone applications. It refers to specific regulatory limitations explained more fully in chapter 8.

1.2Section 333 exemptions: patterns of usage

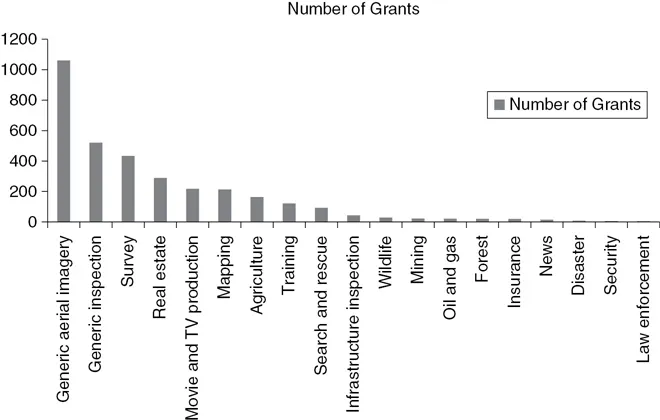

While it was finalizing a general rule for commercial microdrone operation, the FAA granted more than five thousand exemptions from its rules for manned aircraft, allowing commercial microdrone operations proposed by specific individuals and enterprises. Figure 1.1 shows the number of exemptions granted by type of application.

The chart shows that a few types of applications are most common: survey, real-estate marketing, motion picture and television production, mapping, and agricultural support. Many exemption petitioners are keeping their options open by filing for generic aerial imagery or inspection. Others proposed more narrowly defined missions. In many cases, potential users are taking a wait-and-see attitude, hoping to learn from the experiences of the early adopters. Moreover, many of those with exemptions are making only limited use of the new technology, expecting to refine their plans based on experience.

The content of the final rules will remain uncertain for another couple of years, the criteria for granting section 333 exemptions undoubtedly will evolve, and the technology is changing rapidly. The universe of what is feasible now will expand considerably. Still, basic patterns of adoption revealed by the early section 333 exemptions are unlikely to change much for several years because of the relationship between microdrone capabilities and user needs.

Over the longer term, however, designs for airspace management systems allowing intensive use of drones for a broader range of applications—such as delivery of packages—will prove themselves and be deployed, and basic commercial macrodrone configurations will crystallize and be priced. Then, the patterns of activity may shift dramatically.

1.3Aerial surveying

Surveying is a broad term. Agricultural surveying is considered in § 1.6. This section considers surveying of construction sites.

Before construction begins, a surveyor must prepare a contour map, which shows the ground level at various points on the site, and then superimpose a grid. She then calculates the amount of material that must be removed (for a cut) or added (for a fill) to produce the desired surface levels.

Traditionally, surveyors used instruments like theodolites (optical tools for measuring angles), levels, rods, and tapes to prepare the contour map and then calculated the cubic yards of fill or cut from the resulting contour map. Now, airborne sensors, usually employing lasers, precisely measure the distance between an airborne platform and the surface at finely defined GPS points on the ground. Such laser sensing systems are known as LIDAR. Mapping software takes the resulting data and automatically computes what must be done in each of several arbitrarily defined grid squares. The same sensor hardware and mapping software is used, regardless of the type of aerial platform that collects the data—airplane, helicopter, or drone.2 Aerial surveying relies on the ability to fly a precise pattern over the area to be surveyed, so that elevations can be matched with GPS coordinates.

Microdrones provide two advantages over manned aircraft: lower acquisition and operating costs and autonomous navigation systems that fly precise patterns to collect the data.

More sophisticated microdrones can be equipped with the necessary sensors and precise navigation subsystems. Their principal limitation is their short endurance. Fifteen to twenty minutes can be adequate to survey a small field or construction site, with reasonable resolution. Larger scale surveying, however, is inefficient if the drone must land every fifteen minutes to get a battery swap.

Macrodrones powered by internal combustion engines have much longer endurance and thus greater utility. Their ability to fly at higher altitudes may also be advantageous to survey extensive areas. Macrodrones’ greater payloads, however, are of no particular benefit.

It is no surprise that aerial surveying uses have taken a prominent position in the inventory of section 333 exemption applications and grants, because these operations typically occur over specific construction sites, which are under control by customers.

As operators fly their drones under these exemptions, the resulting experiential data will help them refine their strategies for the most cost-effective drone deployment.

1.4Real estate marketing

As soon as microdrones with high-quality cameras were on the market, real estate agents began to use them to capture new photographic perspectives to help sell properties—never mind whether it was legal. As the section 333 process developed, the FAA had little difficulty in approving these operations, because they occur over property controlled by the customer. Of course some realtors also want bird’s-eye views of the neighborhood.

High-quality photographs have long been part of marketing packages for real estate, in print flyers and on webpages. Only the largest and highest priced sites, however, have warranted the cost of aerial photography by helicopter. The aesthetic values of any promotional photography must be high: crisp images, good color, and compelling points of view that emphasize the most attractive features of the property and show off its neighborhood environment.

The necessary flight profiles fit comfortably within the performance capabilities of microdrones like the Phantom, and the Inspire. A skilled DROP and photographer can get all the imagery needed in a 15- or 20-minute flight, and cameras at the GoPro level have adequate resolution and sensitivity. No particular technological development is necessary to make this a cost-effective marketing tool.

There is no particular need for automated flight plan capability, because the best results are obtained when the DROP and the photographer watch the downlinked image as it is being captured and make adjustments in drone position and camera angle to get exactly the shots they want.

Nor are the regulatory challenges particularly great. As with agricultural uses, the drones fly over property controlled by the operator or the person contracting for the service. There is also no reason to fly over people on the ground while the imagery is being captured, although some promotional strategies might want to feature residents or models around an outdoor pool or volleyball net. In those cases, it is relatively easy to obtain advance approval by whoever is going to be in the frame.

The relatively short duration of the necessary flights, and modest size and weight of camera payloads suggest that microdrones can do whatever is necessary. There is no particular need for macrodrones, unless the business model of the photographer requires taking multiple shots at widely separated locations on the same day. Then the short transit times of macrodrones might be an advantage over drones that must be transported on the ground from one location to another. When this is the case, vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) configurations, such as tilt-wing or tilt-rotor designs, would be advantageous, because they can fly like an airplane to transit from one location to another, while retaining the capability of slow flight, low-level operations, and hovering when they are on scene.

1.5Movie and television production

Motion picture and television production on closed sets was the first activity to receive FAA approval via section 333 exemptions. Risk management and regulation were straightforward because the activity takes place on closed sets where the customer exercises detailed control. Risk reduction benefits were obvious because of the dangers of typical helicopter operations involving low level flight and aggressive maneuvers.

Moviemaking, including television program production, involves some of the most demanding types of aerial photography. Compelling story telling is at the center of an acceptable product, and good video storytelling requires a variety of camera angles and a mixture of close shots and long shots. Creative lens manipulation is also necessary to enable objects or people in the foreground to be in sharp focus while the background is blurred, or vice versa. Lighting intensity and direction are important; they must be consistent from shot to shot.

Ultimately, the movie is assembled in an editing process separate from, and later in time than, principal photography. The editor needs shots with multiple camera angles and framing to afford creative choices in the subsequent editing process. When a director discovers during the editing process that he doesn’t have what he needs, one or more scenes must be reshot, and costs soar.

Locations for movie or television shoots involve property controlled by the producer (as on a studio set) or it may involve a public setting for which local government permits have been obtained and security established. Long established practices for principal photography assure the safety of everyone on the location. The incremental risk associated with drone photography is minimal. That is why the FAA was comfortable granting the first set of section 333 exemptions for closed-set movie production.

Cinematographers already use multiple tools so cameras can capture the imagery the director wants. Some cameras are operated from fixed tripods for shots not involving much subject movement. Others are installed on dollies or tracks to permit the camera to move along with the acti...