- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Decision-making Processes in Airline Operations Control

About this book

Previous studies conducted within the aviation industry have examined a multitude of crucial aspects such as policy, airline service quality, and revenue management. An extensive body of literature has also recognised the importance of decision-making in aviation, with the focus predominantly on pilots and air traffic controllers. Understanding Decision-Making Processes in Airline Operations Control focuses instead on an area largely overlooked: an airline's Operations Control Centre (OCC). This serves as the nerve centre of the airline and is responsible for decision-making with respect to operational control of an airline's daily schedules. The environment within an OCC is extremely intense and a key role of controllers is to make decisions that facilitate the airline's recovery from frequent, highly complex, and often multiple disruptions. As such, decision-making in this domain is critical to minimise the operational, commercial and financial impact resulting from disruptions. The book examines many aspects of individual decision-making in airline operations, and addresses the deficiencies found by presenting to the reader an examination of the relationships among situation awareness, information completeness, experience, expertise, decision considerations and decision alternatives in OCCs. The text utilises a multiple case study approach and proposes a number of relevant and important implications for OCC management. Practical outcomes highlight the need for enhancing training programs enabling existing controllers to readily identify and classify elements of situation awareness and decision considerations as a means of improving the decision-making process. They also draw attention to the need for airline OCCs to understand the extent to which industry experience and expertise of controllers is important in the selection of future staff.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Background and Underlying Theory

Chapter 1

Introduction

The Aviation Industry

Aviation is an exciting, challenging industry that is constantly evolving and responding to innumerable pressures. In this industry, safety is paramount and is controlled rigidly by a comprehensive, regulatory framework of standards, practices and guidelines. Notwithstanding the implications and consequences of a safety mindset, airlines also operate within critical economic margins, necessitating the optimum efficiency of resources and minimisation of costs. A significant characteristic of the aviation industry is the nature of its unpredictability, which results frequently in disruption to schedules, the occurrence of additional costs and unhappy passengers. To respond to these operational disruptions, decisions must be made that help to mitigate the effects of disruptions and decisions yielding optimal results may well be the difference between survival and bankruptcy. Certainly, the consequences of poor operational decisions can be severe.

The Operations Control Centre

No two airlines in the world operate with identical schedules: rather, each airline designs and operates its own network of schedules and it is the management of this network that is central to an airline’s operations. At the heart is the Operations Control Centre (OCC) which serves as the airline’s nerve centre. The main function of the OCC involves the planning and coordination of the disruption management process to achieve network punctuality and customer service while utilising assets effectively and minimising costs. The OCC domain is a highly complex, dynamic, and fast paced environment in which decisions made by the OCC controllers facilitate disruption recovery. Clearly then, decision-making in this environment is critical, so any improvements to the decision-making process are likely to result in more effective ways in which OCCs can manage disruptions.

The OCC is provided with a planned schedule of flights, reflecting the expectations of booked passengers and setting the parameters within which airline operations are based. The schedule indicates the origin and destination of each flight the airline operates and the days and times at which the flights are planned. The primary scope of responsibility of an OCC lies with the control of flights within a particular period of operation. In international operations, this control may be over several days. However, in domestic operations, control is usually within a calendar day. The chief function of an OCC is to ensure that as far as possible, the operation mirrors the planned schedule. This is performed by monitoring the progress of flights, identifying potential or actual operating problems, and taking corrective actions in response to disruptions.

An Operations Control Centre may vary in terms of location, physical structure, and composition. Depending upon the size of the airline, the centre may be physically located within an airline’s head office at a city or airport location. The OCC may consist solely of a group of decision-makers with responsibility for coordinating and controlling aircraft movements. Generally though, the OCC is large enough to include representatives from Pilot and Cabin Attendant Crewing, Engineering, Flight Despatch, airport functions, various commercial and customer service functions, and liaison with Air Traffic Control and Meteorology. A centre incorporating these areas may be known as an Airline Operations Control Centre (AOCC), Integrated Operations Control Centre (IOCC) or a Network Operations Control Centre (NOCC). For the purpose of clarity and consistency throughout this book, the centre will be referred to as an OCC.

Disruption Management in OCCs

There is greater than ever emphasis on maintaining schedule regularity in airline operations, because one of the key measures of an airline’s worth and credibility in terms of passenger satisfaction and therefore loyalty is its level of on-time performance. However, airlines constantly face operational disruptions for a variety of reasons such as adverse weather conditions, aircraft maintenance problems, limitations and requirements, air traffic flow and congestion and crewing issues as well as many others. As far as the travelling public is concerned, these disruptions are experienced as flight delays, cancellations or diversions, but part of the disruption recovery may also involve strategies that upgrade or downgrade aircraft sizes, necessitate additional flying to position aircraft for flights or involve moving and rebooking passengers.

Controllers in OCCs need to instigate a series of actions so that the airline recovers from these disruptions promptly. However, the disruptions are often highly complex, in terms of the challenges encountered within individual disruptions, or in terms of the complexities of managing simultaneous disruptions. The necessity to recover from disruptions, often under severe time constraints, calls for rapid and accurate decision-making by controllers in OCCs. Given these challenges, the study described in the second part of this book examines ways in which OCC controllers go about the decision-making process.

Decision-making Process

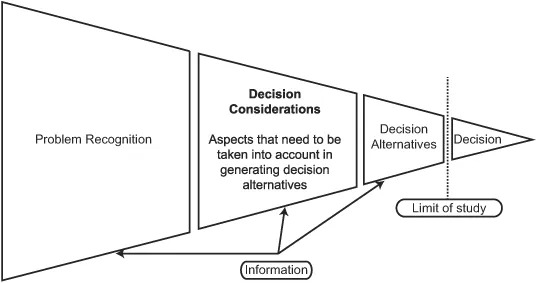

Figure 1.1 presents the focus of the study described in Part Two in terms of the overall decision-making process. The model indicates that the decision stage is predicated on a number of steps including problem recognition, identification and weighting of decision considerations, and generation of alternatives. The model also indicates that the decision-making process is examined only to the point at which a decision may be made and does not include analyses of actual decisions made. This is because problems in OCCs typically have several solutions, all of which may be feasible and acceptable for resolving a problem. Thus, the focus of the study is predominantly on the individual decision-making processes that enable decisions to be reached, taking into account the extensive range of decision alternatives from which a choice may be made and the limited worth of comparing decision choices.

Previous studies on decision-making have focused on ways in which people make decisions in various situations and the extent to which the effectiveness of decisions can be improved. The need to understand, develop, and enhance decision-making processes has been driven by the growing sophistication and complexity of environments in which decisions often need to be made rapidly with incomplete or inaccurate information. Decision-making in these environments needs to be precise as the consequences of poor decision-making are often very costly.

In the aviation industry the importance of decision-making has been recognised with the focus predominantly on decision-making processes by pilots and air traffic controllers. Not until fairly recently has attention been given to OCCs. Yet, this decision-making environment is extremely intense and the outcomes of decisions critical.

Figure 1.1 Focus of the study in terms of the overall decision-making process

Research that has been undertaken in relation to OCCs has focused on disruption recovery strategies and much of it has involved computer modelling and analysis. Computer-based systems assist controllers by providing information and limited decision-making support. The issue is that the complexity of the problems and need for very rapid decision-making in limited time and with ambiguous or incomplete information limits the usefulness of these systems. In other words, these systems are unable to cope with the intricacies of significant isolated disruptions never-lone the additional complications created by concurrent multiple problems that inevitably occur. Further, the models do not take into account the decision-making processes of individual controllers. However, human intervention in the decision-making process in OCCs is critical as a means of coping with the novelty and complexity of situations. This may help to explain why current practice of OCC controllers is to handle disruption recovery manually rather than rely on computer-based systems. There appear to be very few studies investigating controllers’ decision-making processes; yet determining these processes may enable airlines to improve decision-making in OCCs. Part Two of this book considers these processes by examining the relationships among situation awareness, information completeness, experience, expertise, decision considerations, and decision alternatives in OCCs.

Summary

This chapter has provided a brief introduction to the Operations Control Centre of an airline and the key functions performed therein. The main message is the importance placed on efficient disruption management in such a highly complex and constantly changing environment, where human decision-making processes are critical to schedule integrity.

Chapter 2

Decision-making

Introduction

Decision-making underpins many critical activities in the aviation industry. Whereas much research has examined decision-making of pilots and air traffic controllers, very little has considered decision-making processes of controllers in OCCs. Yet, efficient, timely and accurate decision-making in the OCC is vital for its contribution to the operational and commercial success of an airline. This chapter explains decision-making in terms of its importance and relevance to OCCs and investigates variables that may influence the generation of decision alternatives or options, namely situation awareness, information completeness, decision-making styles, experience, expertise, and time.

Definition of Decision-making

A decision has been defined as ‘... a commitment to a course of action that is intended to produce a satisfying course of action’ (Yates, Veinott and Patalano 2003: 15) and decision-making as ‘... intentional and reflective choice in response to perceived needs’ (Kleindorfer, Kunreuther and Schoemaker 1993: 3). In an airline OCC, decision-making involves a process of monitoring the progress of flights and reacting to operational disruptions in order to improve on-time performance, reduce operational costs, and increase customer satisfaction. Clearly, decision-making in an OCC environment is critical to all aspects of airline operations.

Importance of Decision-making

The decision-making process has long been regarded as one of the most important and pervasive of activities as it affects many day to day endeavours. As a result, extensive studies about decision-making have been conducted stemming from a desire to understand how people make decisions in various situations and how the effectiveness of decision-making may be improved. The growing sophistication and complexity of decision environments has created a greater need for understanding, developing, and supporting effective decision-making. Of course, part of this push for greater understanding is the need to gain a greater awareness of the consequences of poor decisions.

In response to these needs, considerable research has examined decision-making and its relationships with uncertainty, ambiguity and risk, choice, judgment, experience, and expertise. A common goal evident in much of this work has been a focus on improving decision-making processes and identifying factors and dimensions that are related to those processes in order to improve decision outcomes. The research has also led to a greater understanding of decision processes employed by experts. In many disciplines or domains, decision-making is recognised as being highly complex and sensitive to task and domain factors such as expertise, time, and information. These aspects also characterise decision-making in aviation.

Decision-making in Aviation

In aviation, considerable research has examined decision-making processes with regard to aspects such as tourism and aviation policy, airline profitability, airline service quality performance, revenue management, and aviation business services marketing. However, studies that have examined decision-making in aviation have focused predominantly on decision-making by commercial and military pilots and air traffic controllers and much of it has emphasised decision-making in relation to safety aspects. This is because pilots and air traffic controllers need to make precise, informed decisions often with ambiguous information and often with limited time in an environment in which the consequences of poor decision-making may be catastrophic. Despite the amount of research in aviation decision-making, limited studies appear to have been conducted in airline OCCs and the research that has been conducted has yet to consider decision-making processes of controllers in these OCCs.

Decision-making for Disruption Management in OCCs

Decision-making in OCCs is made difficult by the numerous operational disruptions faced by airlines. These disruptions result from factors such as inclement weather, maintenance breakdowns, pilot and cabin crew limitations, passenger handling problems, air traffic control clearances, and airport congestion and are most visibly evident in delays, cancellations, and diversions. Although poor decisions of controllers in OCCs may not culminate in safety incidents, sound decision-making is critical to achieve desired operational outcomes such as on-time performance, customer satisfaction, economic operations, and rapid recovery from operational disruptions.

Past research in airline operations has investigated planning activities such as schedule optimisation and fleet assignment (e.g., Ball 2003). Some of this research has resulted in the development of models that assist airlines to plan schedules for profit maximisation and optimum carriage of passengers (e.g., Soumis, Ferland and Rousseau 1980). Other models have augmented these by incorporating fleet assignment (e.g., Lohatepanont and Barnhart 2004), maintenance, and/or crew assignment (e.g., Lettovsky, Johnson and Nemhauser 2000).

Managing the operations on a current day basis though is quite different from designing optimal schedules. The controllers in an airline’s OCC are charged with this task and when operational problems occur, they need to make decisions quickly and effectively in order to resolve the disruption and minimise passenger inconvenience and cost to the airline. So, a growing body of research is beginning to focus more extensively on decision-making in relation to disruption management, often employing mathematical modelling techniques. For example, researchers such as Clarke (1997) used linear programming and network flow theory to assist airline schedule recovery following disruption and Cao and Kanafani (2000) developed an algorithmic model to analyse the value to the airline of runway availability and the effect on the airline’s schedules. The problem is that to date, none of the models has been able to cope with the complexities of multiple, simultaneous disruptions commonly experienced by airlines.

Literature examining disruption recovery strategies is quite extensive. Much of the disruption research has focused on aircraft routing, aircraft maintenance, and crew scheduling (e.g., Cohn and Barnhart 2003, Lederer and Nambimadom 1998). Some of the disruption recovery strategies have included optimisation models (e.g., Abdelghany, Shah, Raina and Abdelghany 2004, Rosenberger, Johnson and Nemhauser 2003), or have examined the economic effects of disruptions (e.g., Janic 2005). In order to reduce the complexities of these models and enable them to work, assumptions have often been made in order to limit the parameters included in the models. For example, models developed by Talluri (1996) and Rosenberger, Johnson and Nemhauser (2003) did not take into account and therefore were greatly limited by the inability to substitute different aircraft types to solve disruptions, despite typical airline fleets consisting of a variety of aircraft types. The work of Yan and Yang (1996, 2002) and Yan and Tu (1997) resulted in the development of several models but again none of these took into account the ability to change aircraft types to help solve problems; nor did these models consider crew and maintenance parameters. Sriram and Haghani (2003) restricted their study to domestic airline operations and considered only limited maintenance parameters and Rosenberger et. al. (2002) worked with single disruptions.

Despite this extensive research in disruption management, no single optimisation model has yet been developed to address the task required to solve complex operational problems. According to Barnhart, Belobaba and Odoni (2003: 369), ‘... the problem’s unmanageable size and complexity has resulted in the decomposition of the overall problem into a set of sub-problems ...’ These sub-problems typically include network and schedule design, fleet resource assignment, maintenance requirements, and crew scheduling. Further, it is apparent that computer-based tools cannot cope with the limited decision-making times required in disruption management.

These are key points and suggest that regardless of computer-based intervention, the decision-making processes of controllers in OCCs appear to rely largely on the human’s ability to identify, assess and carry out actions to solve disruptions, most likely using a combination of intuition and experience. Indeed, one researcher (Lettovsky 1997) asserts that airline OCCs mostly recover from disruptions manually.

The trouble is that identifying how people use intuition makes airline disruption recovery difficult to comprehend, which may help to explain the deficiencies in the models developed so far. In other words, the research based on developing models to solve operational problems in the industry has had limited success because it has not taken into account the underlying human decision-making processes required to solve problems in such a complex environment.

The complexity is emphasised by the endless variety, uniqueness and combinations of problems. By limiting criteria to single disruptions or simple aircraft pattern changes, or by including little or no crewing or maintenance parameters, the models will never replicate true disruption management. Yet, incorporating all of these parameters, if it could be done, would require so much computer power and extensive calculation time that the optimum decision point would quickly pass. And this is if circumstances remained steady during this whole process: in domestic operations especially, not a reality! It is the work of these and other researchers that has led, in part, to this book as very little research appears to have examined individual decision-making processes leaving a gap between what Clausen, Larsen and Larsen (2005: 1) describe as ‘... the reality faced in operatio...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Operational Definitions of Key Terms

- Preface

- I Background and Underlying Theory

- II Examining Decision-making Processes of OCC Controllers

- References

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Decision-making Processes in Airline Operations Control by Peter J. Bruce in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.