![]()

Chapter 1

Technological Constraints

Pilot: They’ve just gave us [a heading of] 160. We’d like to turn back to the left, to the north, and somehow find our way on to the final for 26.

Controller: AS 630 I’m going to have to take you southbound through the weather.

Pilot: OK. We’ll there’s some weather there that we can’t go through.

Controller: I understand that sir. I’m going to try to vector you through the significant weather

…

Pilot: We’ve got about 10 to 15 minutes of fuel left before we have to depart [the pattern].

Controller: AS 630 can you accept a 210 heading?

Pilot: Negative.

Controller: What can you accept?

Pilot: Why do we keep going right? We’d like to go left to the airport. That’s what we can accept.

Controller: AS 630—standby.

Pilot: [unintelligible …] I have 10 to 15 minutes left but I can’t turn to the right.

Controller: AS 630 you’re going to need to turn at least 20 degrees to the right. There’s a restricted area there. If you can’t take that heading there’s no way you’re going to get into Phoenix. You need to deviate somewhere and you need to turn at least 20 degrees right. There’s a restricted area there.

Pilot: OK. Well I’m not going to fly into a thunderstorm just to avoid a restricted area. If I go through it, I go through it as far to the right as we can, Alaska 630.

Controller: That restricted area has bullets flying in the air. You cannot go in that area. You might get shot down. Turn right at least 30 degrees.

Pilot: It looks good to our left. Why can’t we go north?

Controller: That’s a restricted area if you turn into that sir. You have to turn right to 115 and climb to 11,000.

Pilot: OK. We’re turning right and we’re climbing to 11. Alaska 630.

Recorded transcript, Alaska Airlines Flight 630, Phoenix Approach Control (Retrieved from http://www.LiveATC.net)

Airplane Developments

Even if all the societal influences—legal, regulatory, political, economic, and so on—that limit the operation of non-stop flights to any two points on the globe were eliminated, there would remain engineering parameters associated with any airplane that affect how far it can fly and how many passengers or how much cargo it can carry. Until recently, commercial aircraft were constrained by engine technology and aircraft design from operating very long-distance non-stop flights with enough passengers and cargo to turn a profit.

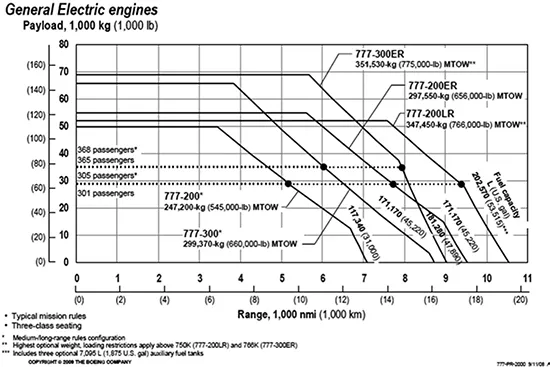

In aeronautical terms, distance travelled is referred to as range. Payload is anything the airplane hauls—passengers, bags, or cargo. The longer the flight, the more fuel needed. For any aircraft, there is a calculated distance that it can fly with a full payload. To fly farther would require additional fuel. The additional weight of the fuel must be balanced by an equal reduction in payload. There is a calculated value, for each airplane, of its maximum range. That maximum range is achieved only with a payload lower than the maximum payload capability, which in turn, is traded for a lower range. Beyond this figure, additional fuel must be loaded, requiring yet additional reduction to the aircraft’s payload. Payload and range are always traded off—you cannot have the best of both at the same time. The concept is illustrated in a payload-range chart (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Payload-range chart

Source: The Boeing Company

“In one fell swoop we have shrunken the Earth” (Juan Trippe)

For all practical purposes, the era of long-range commercial flights began with the jet age. Indeed, some airlines did pioneer trans-Atlantic routes with piston airplanes such as the DC-6B, Lockheed Constellation, or the Bristol Britannia, but not until the introduction of turbojet—and later the turbofan—powered aircraft did non-stop transoceanic flights become routine and expected. It was not until 1957, just before the dawn of the jet age, that more travelers crossed the Atlantic by air than by sea. Air travel growth over the next decade would be staggering. From 1958 to 1969, TWA’s revenue passenger miles flown on long-distance flights grew from 4.6 billion to 19.1 billion. And for Pan Am, the figure grew from 3.8 billion to 17.1 billion. The comfort, economics, and range of the new jet airliners brought air travel within reach of the middle class. Now, a Hawaiian vacation or a tour of Europe was accessible. As Juan Trippe, the visionary founder and CEO of Pan Am put it: “In one fell swoop we have shrunken the Earth.”

No commercial aircraft has revolutionized popular air travel in modern times like the Boeing 707. The four-engine, swept wing airliner, first introduced into commercial service in 1958, could accommodate an all-tourist configuration of 189 passengers. With full fuel and tanks, and a payload of 334,000 lb, the 707-320B had a range of 5,750 nautical miles (nm) and could achieve an economical cruising speed of 550 mph at 35,000 ft.

Within a year of Boeing’s introduction of the 707, Douglas rolled out its competitive response—the DC-8, a four-engine jet transport almost identical to the 707. Pan American World Airways ordered 20 707s and DC-8s, and flew both types until standardizing its fleet with the Boeing model, and disposing of the DC-8s. By 1960, Pan Am had employed its fleet of 707s on routes to five continents, spanning the globe from New York to Sydney and from Buenos Aires to Tokyo, setting the standard to which the industry was trying fast to catch up. Ultimately, Pan Am would acquire 120 707-300 intercontinental series aircraft. With a capacity of 135 passengers and a maximum cruise speed of 600 mph, the 707-321 (Boeing’s model nomenclature for the Pan Am aircraft), would dominate the Pan Am fleet until being phased out with the introduction of the 747 beginning in 1969.

Douglas competed head to head with its DC-8. Although the 707 would outsell its rival by nearly 50 percent, the Douglas aircraft had an advantage in that its design allowed for several stretched versions of the airplane. The DC-8-61, which first flew in 1961, had capacity for 252 passengers in an all-economy configuration. In 1967, the company introduced the DC-8-62. First flown by Braniff International, this model, which was six feet longer than the original DC-8, was given a new, wider wing, with additional fuel capacity, to extend its range to 5,500 statute miles (sm), sufficient for SAS to operate non-stop from Copenhagen to Bangkok.

Widebodies: New Economics, New Possibilities

The next revolution in air travel would come barely a decade after the dawn of the jet age with the introduction of the new widebody airplanes. These giants demonstrated two breakthroughs. One, of course, was their sheer size and capacity. The other was the introduction of high-bypass-ratio turbofan engines. The Pratt & Whitney JT9D, the General Electric CF6 and the Rolls-Royce RB.211 were quieter and more fuel efficient than their predecessors, and in combination with greater fuel carrying capacity and structure innovations of the new widebodies, provided greater range capability.

First to market, and in every way the icon of this new generation of massively large airliners, was the Boeing 747. In 1966 Pan Am, as the launch customer, ordered 25 airplanes for $550 million and first flew the type on a revenue flight from New York to London in January 1970.

The 747-200B’s gross weight was 836,000 lb with a payload capacity of 144,520 lb and a range of 6,854 nm Cruising speed was 564 mph (mach .85 at a cruising level of 35,000 ft). With a maximum fuel load and a reduced payload of 87,800 lb, range increased to 8,706 nm (Grant, 2002).

The McDonald Douglas’s DC-10 and Lockheed’s L-1011 TriStar were designed to fill the gap between conventional narrowbody aircraft and the 747, which was nearly double the size. Both aircraft were three-engine “tri-jets,” with one engine mounted under each wing and one at the rear of the fuselage under the vertical stabilizer (the L-1011) and the other (the DC-10) with the engine itself mounted on the lower portion of the vertical stabilizer. Unlike the 747, which was designed primarily for intercontinental travel, the DC-10 and L-1011 were initially developed for high-capacity US transcontinental domestic routes. The DC-10 first entered service in 1971, and the L-1011 was introduced a year later. Several versions of both aircraft were developed, and later versions of each type would add true intercontinental range capability.

By the early 1980s, the DC-10-30 had become the most popular variant. The airplane allowed airlines to compete on intercontinental routes that were uneconomical for the 747. The DC-10 provided about 75 percent of the capacity of the 747, using 75 percent of the power and thus, only 75 percent of the cost. With a gross weight of 468,000 lb, it provided seating capacity for 345, a maximum payload of 74,200 lb and a range of 4,500 nm and up to 6,000 nm with a reduced payload. The Extended Range version greatly extended the reach of the airplane, allowing flights up to 7,000 nm. The DC-10 was widely used by airlines all over the world, and was ideally sized for carriers such as SAS or KLM operating long-haul routes with relatively thin demand.

The L-1011 shared very similar characteristics with the DC-10, but lost the race to market when it was introduced in May 1972, eight months after its rival from McDonnell Douglas, a delay that would cost it dearly in sales. With full fuel, the L-1011-200 had a range of 4,884 nm. Reducing the payload to 42,827 lb extended the range to 6,204 nm. Total capacity was 400 economy-class passengers in a 10-abreast seating configuration. The L-1011 did have a major disadvantage compared to the DC-10, as range on the TriStar could only be increased through a decrease in weight. The result was a design compromise in the form of the long-range L-1011-500. The -500 could accommodate 305 passengers and fly 6,000 nm. Once again, Pan Am was the launch customer, using the aircraft primarily on its routes from New York and Miami to Latin American destinations.

The main benefit to industry and consumers of the widebodies was in comfort and price. For airlines, the larger airplane reduced the price per seat (“seat mile” cost), facilitating discount fares to fill those cavernous cabins. For the most part, the widebodies flew the same routes as the 707s or DC-8s but could accommodate more passengers in greater comfort.

There remained, however, an unfilled gap in the market for an airliner that could carry a reasonable payload on very long-distance flights. Pan Am wanted an airplane that could profitably fly from New York to Tokyo non-stop. It also sought non-stop capability for San Francisco–Hong Kong and Sydney–Los Angeles. These routes were beyond the range of existing airliners carrying any reasonable loads. Having no airplane to compete with the smaller DC-10 and L-1011, and seeing a niche market in long-haul, reduced capacity routes, Boeing decided to fill that gap by taking the 747 and shrinking it. With some structural modifications, the airplane would be capable of fulfilling Pan Am’s requirements. Additional carriers, including South African Airways, Iran Air, China Airlines, Korean Air, and the Civil Aviaiton Administration of China (CAAC), also sought such an aircraft that could service their long, thin routes.

Boeing launched the 747-SP (Special Performance) program in 1973. The 747 fuselage was shortened by 48 ft, allowing for 331 single-class passengers or 268 in a mixed-class configuration. Various structural changes to the 747 were made, including a larger vertical stabilizer, a double-hinged rudder, and lighter components in the wings and fuselage. Powered by Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7A turbofan engines, the 747-SP offered shorter takeoff lengths, faster cruising speed (594 mph) and higher altitudes (up to 45,000 ft). Range with full payload was nearly 7,000 nm (Green, 1978; Davies, 1987).

Pan Am ordered five SPs. The first airplane, delivered in 1976, was placed on the 6,754 sm New York – Tokyo route. The carrier would eventually receive 12 of the type, deploying them all on trans-Pacific routes. With a reduced payload (276 seats in single-class configuration) the airplane had a range of 7,650 sm. With the new long-range airplane, Pan Am inaugurated non-stop Los Angeles–Tokyo service, and launched the longest routes ever flown at the time: San Francisco–Hong Kong (6,914 sm and 14 hours 40 minutes block time, gate to gate); and Los Angeles–Sydney, at 7,487 sm the longest route as measured by distance, but also scheduled at 14 hours 40 minutes block time, the same travel time as the shorter San Francisco–Hong Kong flight, due to more favorable wind conditions on the South Pacific route (Davies 1987; Pan American World Airways, 1984).

South African Airways (SAA) was the second 747-SP customer. Its original intention was to deploy a smaller aircraft on its existing 747-200-operated routes to Europe. But the aircraft would prove a strategic asset to SAA, as African airspace bans went into effect and the airline had to fly around the bulge of Africa to reach Western Europe. Iran Air also introduced the 747-SP in 1976, flying from New York to Tehran, a distance of 6,131 sm.

Twin-Engine Airplanes Rewrite the Rules

The next breakthrough in range capability occurred when Boeing introduced its 767-200 twin-engine widebody jet in 1982. Ultimately, Boeing would develop three variants of the airplane. The first one introduced, the -200, carried 290 passengers in a 2-3-2 economy seating configuration, very popular with passengers as it meant that 86 percent of seats were either window or aisle. Boeing offered the airplane with either Pratt & Whitney JT9D or General Electric CF6 turbofan engines, each with 48,000–50,000 lb of thrust. The basic version has a maximum takeoff weight of 300,000 lb and a range of 4,100 miles. The Extended Range (ER) version increased maximum takeoff weight to 345,000 lb and a range of 5,000 nm.

The 767 was the first twin-engine airplane designed for oceanic flight, and several airlines quickly employed it on such routes. First to operate revenue flights on the North Atlantic was El Al which, in 1984, flew the 767 non-stop from Montreal to Tel Aviv. TWA, which had ordered 10 units, envisioned the airplane on trans-Atlantic routes that could not support the larger widebodies. After initial modifications to comply with ETOPS regulations, TWA inaugurated a 767 non-stop service from its hub in St. Louis to Paris in 1985. The fuel efficiency of the smaller twin-engine airplane would make the route financially viable. While the seat mile cost (cost of carrying one seat per mile) on the 767 was about the same as that of a much larger 747-200, the overall trip cost was far lower due to the fuel savings, with the smaller 767 burning only half the fuel of the 747. Air Canada also used the 767 on flights from Halifax to the UK, and Qantas operated the 767 on ETOPS flights over the South Pacific and the Tasman Sea (Birtles, 1987).

Following the success of its A300 widebody twin jet, Airbus launched its A330/A340 program in 1987. The two airplanes were designed with a common fuselage, wings, and flight systems. The primary distinction between the two is that the A330 is a twin-engine airplane while the A340 is a quad engine. Each was designed for a different mission. The A340 was developed for more efficient long-haul flying. The advantage of four engines is that the airplane requires less thrust for takeoff (retaining more thrust and fuel for climb and cruise) and avoids the constraints of ETOPS routing restrictions that, at the time, applied exclusively to twin-engine aircraft. (Technological developments, economics, and market conditions would eventually trump these advantages, but the reasoning was sound at the time.) The baseline model, the A340-300, was first flown in 1991. With a maximum takeoff weight of 606,000 lb and a typical three-class seating arrangement for 295 passengers, it offered a range of 7,200 nm. First deliveries were to Lufthansa and Air France in 1993.

Airbus would go on to develop three variants of the A340: the -200, -500 and -600. The first of the types was the A340-200, which traded size for range. The fuselage of the -300 model was shortened by 14 ft. With a typical mixed-class seating capacity of 263, the aircraft has a range of 7,450 nm.

The -500 and -600 programs were launched in 1997, with the first flight, a -600, occurring four years later. These two models offered a brand new capability from Airbus in terms of capacity and range. When introduced into service in 2002, they provided greater range than any other airliner—an unprecedented 8,500 nm. The A340-500 introduced a new era of ultra-long-haul flying. Slightly longer than the -300 (a 10-foot stretch), the -500 was powered by four 53,000 lb thrust Rolls-Royce Trent 556 turbofan engines. Singapore Airli...