![]()

Chapter 1

Setting the stage

The origins of modern day advertising

The functions of advertising

The effects of advertising: a psychological perspective

Consumer responses

Source and message variables in advertising

Advertising in context: integrated marketing communications and the promotional mix

Classic and contemporary approaches of conceptualizing advertising effectiveness

Plan of the book

Summary and conclusions

As I woke up this morning and stumbled to the bathroom to refresh, I barely noticed the brand of toothbrush and toothpaste I used. I couldn’t escape the brand of breakfast cereal though, because it screamed at me in huge typeface to enjoy my “coco-pops”. I wanted to check the morning news, so switched on the television, only to find a seemingly endless sequence of commercials on every channel I selected, urging me to buy more cereal, get a consumer loan, choose shampoo X instead of Y, collect a great offer at the nearest car dealership, and phone lawyer Z when I had a conflict at work. I had no interest in any of these products or services. Before setting off for work, I saw a glimpse of yester day’s football match, but the billboards surrounding the playing field were more visible than the ball, so the sponsoring only distracted me from what I wanted to see. On my way to the train station I passed numerous signs, billboards and shop windows, each with their own message and several repeating the same message I had seen a mile back. Of course, I did not want to attend to them, and wasn’t even able to do so, since I was using my cell-phone to email a friend. It was only 8.00 am, but by now I had been exposed to over 250 commercial messages ranging from brand names and packaging to billboards, television ads and sponsored events. And of course, none of these messages had in any way affected me, my mood, my thinking or my actions, because I had other things on my mind, and a busy schedule to follow. Or had they?

After reading this book, the answer to this question will be yes, and in more ways than the actor of this anecdote or the reader might have imagined. Although people’s lives differ, there is at least one constant, particularly among those living in Western and Asian-Pacific hyper-industrialized societies and that is the ubi quitous presence of advertising. Indeed, the average US consumer is thought to be exposed to more than a 1,000 commercial messages each day. Did you ever wonder whether and how this advertising works? How consumers make sense of advertising messages? What types of messages ‘get across’, when and why? What impact advertising has on consumer emotions, thoughts and behaviour? That is what this book is about.

Advertising is defined as any form of paid communication by an identified sponsor aimed to inform and/or persuade target audiences about an organization, product, service or idea (Belch and Belch, 2004; Tellis, 2004; Yeshin, 2006). In the present chapter, we set the stage for what is to come in the following chapters by providing the reader with a grasp of the business context, societal context and academic context in which the material in the other chapters must be situated. As such, the present chapter will touch briefly on several issues that are dealt with in more detail in the coming chapters and will highlight the origins and settings of contemporary thinking and research on the psychology of advertising and its translations in advertising practice. More in particular, we will discuss how adver tising practice has evolved through history, how it manifests itself presently, what functions it has in society and how thinking about its effects has developed to where we are now. We conclude this chapter with an outline of the contents of the other chapters.

The origins of modern day advertising

Advertising was not invented yesterday or the day before, but has a considerable history. As McDonald and Scott (2007) claim, the first type of advertising was what we now term ‘outdoor advertising’. Archaeologists have unearthed tradesmen’s and tavern signs from ancient civilizations such as Egypt and Mesopotamia, Greece and Rome, indicating that traders and merchants were keen to tell their community what they had to sell and at what price. Similarly, ads for slaves and household products have been found in early written records of the period. Later, town criers and travelling merchants advertised goods and services and in so doing became the forerunners of today’s voice-overs in television and radio ads (McDonald and Scott, 2007). The Industrial Revolution between 1730 and 1830 especially boosted advertising practice. This increase can be partly explained by the large-scale diffusion of the division of labour that increasingly necessitated informing consumers of the availability of goods and services, the creation of which they were no longer directly involved in, and partly because the Industrial Revolution greatly accelerated the scale of production, creating an obvious impetus for manufacturers to advertise in order to sell their stock. As a result, markets transformed from being mainly local to regional and finally even global. The Industrial Revolution also illustrates the pivotal role of advertising as a necessary lubricant for economic traffic. Without advertising, we would not be aware that certain products or services exist, and consumption would wane. This in turn would directly slow down production. Thus, whereas advertising cannot be said to create consumer needs, it is capable of channelling those needs by reshaping them into wants for specific products and services that manufacturers can supply and that promise to satisfy those needs (cf. Kotler, 1997).

A ‘side effect’ of these trends was the creation and growing importance of the consumer brand: the label with which to designate an individual product and differentiate it from competitors. Since production and consumption became distinct in time and space, consumers needed such an unequivocal label with which they could identify the product of their choice amidst alternatives. Hence, advertising practitioners (who by the mid to end of the Industrial Revolution started to exclusively work as such and thereby created an entirely new profession) were quick to assign unique labels to products and associate them with unique advantages not shared by competitors. The Unique Selling Proposition or USP was born, a summary statement used to meaningfully differentiate the brand from the competition. The creation of a compelling USP was to grow to be the key challenge for professional advertisers in ‘building’ new consumer brands.

The American Civil War and, 50 years later, World War I temporarily slowed down production, only to see an ‘afterburner effect’ after hostilities ceased and societies had to be rebuilt. After the Depression years and World War II, advertising volumes skyrocketed again, to keep up with the production and consumption pace of the period. The post-war economic boom enabled ever more consumers on an ever widening scale to enjoy new products and services, and the concomitant mass introduction of television increased advertising’s reach at an unprecedented rate. This trend is mirrored by the present-day proliferation of the Internet as an advertising medium (Chapter 8). More generally, a brief history of advertising should include a brief discussion of the evolution of the chief carriers of these ad messages throughout history: the advertising media.

The earliest forms of advertising, as noted, used ‘outdoor media’: clay tablets, placards, and, from 1400 onward, handbills and poster bills. Martin Luther used this latter medium when advertising his objections to Roman Catholicism by nailing a poster bill on the Wittenberg church door. Outdoor advertising subsequently evolved from poster bills to billboards, which especially in North America grew out to be one of the most eye-catching icons of increased consumerism with brands such as Kellogg’s, Heinz, Coca-Cola and Palmolive covering large parts of US public space.

Newspapers and magazines are among the main advertising media, especially since their development in the eighteenth and nineteenth century accelerated. An estimated billion people per day read newspapers, and advertisers have been keen on reaching them, especially with display (regular) ads and classified ads (McDonald and Scott, 2007). Interestingly, despite the introduction of television and, more recently, the Internet, newspapers continues to be a popular advertising medium. Although market shares of classified ads are decreasing mainly due to the Internet, newspaper advertising is still second in volume after television, with 30 per cent of all main media expenditures (McDonald and Scott, 2007). Similarly, the advent of the Internet has not led to the demise of magazine advertising, as audiences are ever more specifically targeted with special interest magazines, which continue to be attractive for advertising aimed at reaching consumer segments that share common interests, values or lifestyles.

Television, radio and the Internet complement the array of contemporary mass media. Whereas radio advertising started in the early 1920s in the US, television advertising took off two decades later with a Bulova Watch commercial being shown before a baseball game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and Philadelphia Phillies (McDonald and Scott, 2007). Despite the World Wide Web, television continues to claim the largest share in ad expenditures, accounting for more than $147 billion worldwide in 2005 (McDonald and Scott, 2007). Finally, Internet advertising started in 1994 and has ever since seen yearly growth rates of over 25 per cent. At present, the Internet appears a complementary rather than a substitute medium. Although it has taken away some of the market share from other media (most notably classified ads in newspapers), the Internet will probably coexist next to more traditional mass media, rather than eliminate them as some media gurus have prophesied. In all, despite its humble origins, advertising has grown to be a flourishing business with spending on advertising reaching $574 billion worldwide by 2015 and expected to grow to around $668 billion by 2018 (statista.com, 2015).

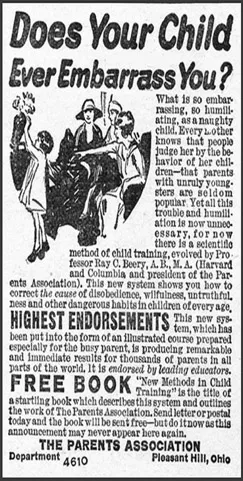

We might look at classic ads with feelings of warm nostalgia or wonder about the sometimes peculiar language use and propositions made, but are the appeals made in those historic ads really fundamentally different from those we find in contemporary advertising? The answer appears to be both yes and no. McDonald and Scott (2007) argue that from the 1800s to the early twentieth century, virtually all print ads used what we would nowadays term an informational or argument-based appeal. They straightforwardly informed consumers what was for sale, at what price and where one could buy it. The approach became known as the ‘tell’ approach, a more subtle variant of the more pressing ‘hard-sell’ approach of ‘salesmanship in print’ that aligned a set of persuasive arguments to convince prospective buyers and thus became known as the ‘reason-why approach’ (Rowsome, 1970; see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Vintage advertisement using an informational appeal

Partly as a reaction to this aggressive approach, a more subtle ‘soft-sell’ approach was developed in the early 1900s that sometimes used an emotional or affect-based appeal, aiming to influence the consumer’s feelings and emotions rather than his thoughts. The development of the soft-sell approach was in line with the societal and academic trend of the time, increasingly to view human nature as governed by instinct, emotions and non-rational processes (Beard, 2005). Despite the impression that the discussion may have given thus far, Fox (1984) has stated that argument-based and affect-based appeals have coexisted through the ages, rather than one approach evolving out of the other. Hence, even the beginning of the twentieth century saw illustrations of emotional appeals next to informational ads much like we see today. Indeed, in today’s advertising practice, hard-sell and soft-sell appeals still coexist, and sometimes reflect distinct philosophies of the ad agencies about what works in advertising (i.e. use of arguments versus use of emotional appeals to sell products; Kardes, 2002).

The functions of advertising

Imagine a world without advertising. What would it be like? Certainly, there would be no unsolicited harassment by sales representatives, no distraction by neon signs and billboards, no interruptions to movies on TV by commercial breaks. But before sighing with relief, also think of the following. Perhaps, there would also be no newspapers and magazines, no television, no radio, no Internet. All these media depend on advertising revenues for their existence. There would be fewer great sports competitions such as tennis, football and Formula One, because all depend largely on commercial sponsorship. And, on a personal level, your knowledge of ‘what is out there’, what products are available, with what attributes, at what price and at which outlet, would be seriously impaired. In short, advertising does have its place in society, both at an aggregate and an individual level. In contemporary industrialized societies, advertising serves several functions: facilitating competition, communicating with consumers about products and services, funding public mass media and other public resources, creating jobs and informing and persuading the individual consumer.

First, advertising facilitates competition among firms. Advertising enables firms to communicate with consumers fast and efficiently, and thereby plays an important role in the competition between firms for consumer attention, competition for consumer preferences, choice and, of course, consumer financial resources. Second, advertising is the prime, and perhaps only, means companies have to inform consumers about new and existing products. If a firm offers a product that is cheaper than that of competitors, but equally good, they need consumers to learn about this. And the key way to achieve this is by advertising. Relating this to the previous function, as a result, the competitor may go down in price, thus stirring competition between the two. Third, as alluded to before, advertising is a key source of funding for major mass media in the US and many other countries. Newspapers, TV, radio and certainly many free services on the Internet (e.g. search engines such as Google or Bing) would not exist if it were not for advertising expenditures. On the other hand, to prevent full dependence on advertising revenues, countries such as Great Britain, Germany and the Netherlands still maintain a public service broadcasting system that is publicly rather than commercially financed (e.g. the BBC in Great Britain, or ARD and ZDF in Germany). Fourth, the advertising industry is an important employer. Earlier we referred to the huge volume of expenditures in the industry. Add to this the number of employees in advertising related industries – a total of over 300,000 worldwide in the year 2000, and estimated to grow at a yearly rate of 32 per cent compared to 15 per cent for other industries – and it becomes evident that a world without advertising would produce fewer jobs, less competition and thus less economic activity.

Related to these societal functions are two important functions of advertising at the individual level: to inform and persuade the individual consumer. When advertising’s function is to inform, the emphasis is on creating or influencing non-evaluative consumer responses, such as knowledge or beliefs. When trying to persuade, in contrast, the focus is on generating or changing an evaluative (valenced) response, in which the advertised brand is viewed as more favourable than before or vis-à-vis competitors.

As mentioned earlier, advertising’s key objective is often to provide information on what is available, where and at what price. There is one basic motive for an advertiser to use an informational appeal: to communicate something new and potentially relevant about a product, service or idea. At first glance, this would imply that the information function is primarily used for new product or service introductions, but reality appears more complex than that. Use of advertising to inform is made widely and for varying purposes. For instance, Abernethy and Franke (1996) have shown that the information function varies with product category: informational appeals are used more frequently for durable goods (e.g. products that can be used repeatedly such as refrigerators, cars or furniture) than nondurable goods (e.g. food items, cosmetics or holidays). Moreover, ads in developed, industrialized cultures (e.g. the US, Canada) use informational appeals more often than ads in less developed countries (e.g. India, Saudi Arabia, Latin America). What information do informational appeals convey? The study by Abernethy and Franke (1996) revealed that the most frequently communicated types of information are about performance, availability, components and attributes, price, quality and special offers.

There are also moments in the life of a product when specific informational appeals are called for. Typically, p...