- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Principles of Valuation

About this book

An entry level introduction to valuation methodology, this book gives a straightforward narrative treatment to the subject matter with a multitude of examples and illustrations, contained in an easy to read format.There is a strong emphasis on the practical aspects of valuation, as well as on the principles and application of the full range of valuation methods. This book will serve as an important text for students new to the topic and experienced practitioners alike. Topics covered include:

- property ownership

- concepts of value

- the role of the valuer

- property inspection

- property markets and economics

- residential property prices and the economy

- commercial and industrial property

- methods of valuation

- conventional freehold investment valuations

- conventional leasehold investment valuations

- discounted cash flow

- contemporary growth explicit methods of valuation

- principles of property investment.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Principles of Valuation by John Armatys in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Construction & Architectural Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

11 Property Ownership

Value is defined in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary as: “The material or monetary worth of a thing: the amount of money, goods etc. for which a thing can be exchanged or traded”. It is important to be clear about what is being valued and this chapter focuses on the ownership of rights in landed property, or real estate, as these define the thing to be valued. This chapter explores what is meant by real property and examines the different legal interests in property that can exist.

The meaning of real property or land

Property means anything which belongs to a person — that is anything which is proper to that person. Real property (or real estate or realty) refers to one of the two main classes of property, land and buildings. The other main class of property is personal property (or chattels) such as furniture, money and clothing. Property can also be an intangible asset, for example brands, copyrights and patents. These are collectively referred to as intellectual property. This book is only concerned with real property.

Real property or land includes not only the surface of the earth, but everything above and below it, from as high up in the sky as is necessary for the ordinary use and enjoyment of the land down to the centre of the earth. Land includes buildings and other structures built on it.

There are different ways of owning, or holding, rights in real property (referred to as tenure, from the Latin tenere, meaning to hold) and it is vital to be clear what form of ownership is being valued. It is not possible to own or value property as such because what a land owner has is an interest in property, and this interest is what the surveyor is valuing.

This chapter outlines the nature of different forms of property ownership. These provide a framework for the anticipated future benefits associated with the particular form of ownership being valued, for example the right to occupy the property or the possible future rent and capital sums which may be received. Understanding the nature of legal interests is a vital factor in assessing the value of the property concerned.

The nature of legal interests in property

There are two main types of legal interest (which lawyers call “estates”) in land, freehold and leasehold.

Freehold interests

All the land in England, Wales and Northern Ireland is owned on a freehold basis. The freeholder (the owner of a freehold interest) is effectively the absolute owner of the land, although, strictly speaking, the land is held under the crown. Some rights to extract minerals are excluded and various authorities have powers to acquire rights over the land, for example to lay pipes or erect electricity pylons, or to compulsorily acquire the interest.

Freehold is the highest form of ownership. The owners of freehold interests have no time-limit imposed on the ownership of their property, so their rights exist in perpetuity, that is forever. Freehold owners are able to do what they like with their land, subject to compliance with the law and with any contracts they have entered into with other people.

Freeholders are in a privileged position. They can sell their land if they wish, or, if they retain their property until their death, the freehold interest forms part of their estate and can be passed down to their heirs. Their land ownership may extend to thousands of acres, or they may own a small house, but regardless of the size of their land holding the freeholders will be the kings of their castle. They cannot normally be dispossessed against their will. Probably the only exception to this is where a legal interest is subject to compulsory purchase by local or central government or another body with compulsory purchase powers, in which case they are protected by law from unjustified use of such powers and compensated for their losses.

Companies and other organisations can own interests in land in exactly the same way as individuals. Indeed, most of the central areas of the major towns and cities in the UK are owned by pension funds, local authorities and major property companies.

Freeholders are in a position to exercise a high degree of control over their land. They can choose to develop, improve, maintain or even neglect their property, with no fear that a superior owner will penalise them for their actions. However, freeholders are not entirely free to do what they wish. They are subject to the rights of others and to many statutory restrictions, including the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, which imposes a requirement to obtain planning permission for “development”, that is building and similar operations or making a material change of use of the property. This means, for example, the owner of a freehold interest in a property currently used for residential purposes would not be able to start using it as offices without planning permission.

Leasehold interests

Although freeholders are able to sell their freehold interests, normally without hindrance, they may wish to retain ownership and derive a rental income by allowing another to benefit from occupation of the property. In these circumstances the freeholder may create a leasehold interest by granting a lease, which is a legal interest in property which is held either for a fixed time or for a period capable of being fixed by notice.

When a lease is granted the freeholder becomes the landlord (or lessor). The leaseholder is the tenant (or lessee).

The commencement date and duration of a fixed term lease must be certain before the agreement takes effect. While the leasehold interest must be shorter in duration than the freehold interest, it can be created for a short time, for example one year, or a very long time, for example 999 years. Leases do not need to be “in possession”, it is possible to grant a lease that starts any time up to 21 years in the future. At common law a lease for a fixed term automatically expires by effluxion (flowing out) of time.

A periodic tenancy (for example a tenancy from year to year, or a quarterly, monthly or weekly tenancy) carries on automatically from period to period until it is terminated by a notice to quit served by one of the parties. The notice required is one full period, or six months, whichever is less.

If a tenant no longer wishes to retain the interest in the property the leasehold may be transferred (or assigned) to a new tenant or surrendered to the landlord.

Ground leases

There are many examples where freehold owners of large sites capable of development choose not to sell their freehold interests to developers, but instead prefer to grant a long leasehold interest of 99 years, or 125 years or more, with leaseholds of 999 years in length not being uncommon. This was common practice in the 19th century when the release of land on a long leasehold basis facilitated the expansion of residential areas in larger towns and cities in the UK. In the modern era this has also happened with freehold land held by local authorities which has been leased to developers on long leases for residential, commercial, industrial and other uses. In these circumstances, the freeholder will receive an annual income from a property developer and their successors (anyone who later buys or inherits the leasehold interest) over the term of the lease. Such an income is normally referred to as a ground rent, and the long leasehold interest is commonly referred to as a ground lease.

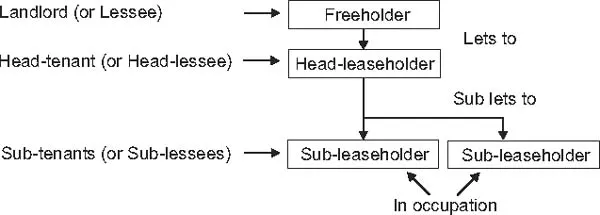

The developer who acquires a ground lease may build on the site. On completion of a residential development the developer may wish to sell the newly constructed houses to owner-occupiers. Since the developer does not possess a freehold interest freehold interests cannot be sold to the owner-occupiers. In such circumstances several new leasehold interests may be granted to each owner-occupier for a term of years which must be less than the term of years the developer holds. The developer would then be referred to as the head-leaseholder and would hold the head-leasehold interest. The individual owner-occupiers would be referred to as the sub-leaseholders and they would each own a sub-leasehold interest. In this way it is possible for several legal interests to exist in the same property, with a freeholder, a head-leaseholder, and potentially an unlimited number of sub-leaseholders.

Sub-lessees may themselves sublet and thereby create further leasehold interests.

Figure 1.1 The creation of legal interests

Occupational leases

Leasehold interests are regularly created when the owners of freehold commercial property grant leasehold interests to tenants who wish to occupy property in order to carry on their businesses. These are often referred to as occupational leases and may typically be granted for five, 10 or 15 years at the market rent, subject to the leaseholder paying rent quarterly or monthly, in advance. The rent will normally be reviewed at regular intervals, often every five years. Each review is normally an opportunity to increase the rent to the market rent at the time of the review. This of course presupposes that rental values have increased during the period between reviews. Lower quality commercial buildings may be let for much briefer periods, often on yearly, six-monthly or quarterly periodic tenancies.

A major difference between a freehold and a leasehold interest is the degree of control to which a leaseholder is subject. It is clear that the freeholder will only agree to create a leasehold interest if they feel that their own rights will not be harmed by the rights of the leaseholder.

Reversionary interests

A reversionary interest is an interest where land is owned by a person but it does not entitle them to present possession. When the term of a leasehold interest expires, the property will revert to the grantor of the interest, who at common law will normally be entitled to occupy it themselves, or to receive its market rent, or to redevelop it.

Statutory regulation, however, may provide exceptions to this rule. Although a detailed examination of these exceptions is beyond the scope of this book they may have a significant impact on the value of the rights of an owner and need to be reflected in the valuation. Examples include the Leasehold Reform Act 1967 and subsequent acts affecting residential property held on long leases and the Landlord and Tenant Acts which give protection to business tenants. For further information on these and other aspects of statutory valuation readers are referred to texts such as Valuation: Principles into Practice and Statutory Valuation (see further reading below).

Other legal interests

It is worth mentioning commonhold as an alternative to leasehold interest. This is a relatively new form of tenure which allows freehold ownership of individual flats, houses and non-residential units within a building or an estate. Unlike a leasehold, a commonhold provides a perpetual interest in the individual unit with the rest of the building or estate forming the commonhold being owned and managed jointly by all the individual unit-holders through a commonhold association. The take up of this form of legal interest has not been widespread and it remains fairly unusual.

Other legal interests include easements, such as rights of way and rights to light, wayleaves, allowing access to land or the right to lay and maintain pipes and wires in or over land, restrictive covenants and mortgages.

A restrictive covenant is in effect a promise not to do something. This is specified in the deeds of the property and is binding on successors. It could for example restrict the type and density of development that can be carried out on land, or it could be a promise not to use land to keep chickens or not to build boundary walls around the open-plan front gardens of a housing estate.

A mortgage usually arises in the case of a loan taken out to help finance the purchase of a house or finance the expansion of a business. As secu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Property Ownership

- Chapter 2: Concepts of Value and Glossary

- Chapter 3: The Role of the Valuer

- Chapter 4: Property Inspection

- Chapter 5: Property Markets and Economics

- Chapter 6: Residential Property Markets

- Chapter 7: Commercia Property Markets

- Chapter 8: Introduction to Methods of Valuation

- Chapter 9: The Comparison Method

- Chapter 10: The Profits Method

- Chapter 11: The Residual Method

- Chapter 12: Cost Based Valuation Methods

- Chapter 13: The Time Val of Money and Valuation Tables

- Chapter 14: Freehold Investment Valuations

- Chapter 15: Conventional Leasehold Investment Valuations

- Chapter 16: Discounted Cash Flow

- Chapter 17: Contemporary Growth Explicit Methods of Valuation

- Chapter 18: Principles of Property Investment

- Index