![]()

2. Cross-Border Partnership in Tourism Resource Management: International Parks along the US-Canada Border

Dallen J. Timothy

School of Human Movement, Sport and Leisure Studies, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH 43403, USA

This paper examines cross-border partnerships in three international parks along the US-Canada border based on principles of sustainable tourism. A model of intensity of cross-border partnerships is developed, and areas of coordination examined include management frameworks, infrastructure development, human resources, conservation, promotion, and international- and local-level level border concessions and treaty waivers, all of which play a part in the sustainable management of trans-frontier resources. The findings suggest that the more integrated the two sides of an international park are in relation to the border, the higher the level of cooperation will be. Furthermore, the paper demonstrates the importance of bilateral treaties, official treaty waivers, and less formal local cooperation for laying the groundwork for sustainable management of cross-border tourism resources.

Introduction

International boundaries have traditionally been viewed as barriers to human interaction. Indeed many borders have been defined and demarcated precisely for the purpose of limiting contact between neighbouring societies or filtering the flow of people, goods, services, and ideas between countries. As a result, tourist destinations, especially those on national peripheries, have tended to develop in a manner clearly constrained by limits of national sovereignty. The world is full of examples where adjacent regions in different countries share excellent natural and cultural resources, and therefore potential for joint tourism development and conservation. Unfortunately, political boundaries have a history of hindering collaborative planning, which has resulted in imbalances in the use, physical development, promotion, and sustainable management of shared resources.

In many regions the function of international boundaries as barriers is decreasing rapidly, however, and the position of borderlands as areas of contact and cooperation between different systems is gaining in strength (Hansen, 1983; Timothy, in press). Consequently, there are increasingly more opportunities for cross-border cooperation in tourism through national and regional policies that stimulate contact and openness between neighbouring countries (Timothy, 1995a).

One global manifestation of this change is the growth in numbers of international parks that lie across, or adjacent to, political boundaries. Thorsell and Harrison (1990) and Denisiuk et al. (1997) identified more than 70 borderland nature reserves and parks throughout the world; some work together with their cross-border neighbours and some do not. Many other natural and cultural areas that straddle international boundaries have been identified and are currently in the process of being created or are still in the initial discussion phases (see Brown, 1988; Parent, 1990; Young & Rabb, 1992; MacKinnon, 1993; Blake, 1994; Gradus, 1994; Lippman, 1994; Timothy, forthcoming). With improvements in international relations and the growth of the conservation movement, it is likely that trans-frontier parks will continue to be designated in the future.

Conservation efforts and good relations during the twentieth century have resulted in the creation of several international parks and monuments along the US-Canada border. All of these parks have become significant tourist attractions (Timothy, 1995b). Nevertheless, they and their cross-border management have been virtually ignored by tourism scholars. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to examine cooperative tourism management within three of these borderland parks, based on principles of sustainable tourism development.

Sustainability and Cross-border Partnerships

During the 1990s, the concept of sustainable tourism has received a great deal of attention in the academic literature. In their discourses on sustainability, commentators have emphasised a forward-looking form of tourism development and planning that promotes the long-term health of natural and cultural resources, so that they will be maintained as durable, permanent landscapes for generations to come. The concept also accepts that tourism development needs to be economically viable in the long term and must not contribute to the degradation of the sociocultural and natural environments (Butler, 1991; Mowforth & Munt, 1998; Murphy, 1998). According to Bramwell and Lane (1993: 2), four basic practices should form the essence of sustainable tourism development: (1) holistic planning and strategy formulation; (2) preservation of ecological processes; (3) protection of human and natural heritage; and (4) development in which productivity can be sustained over the long term for future generations. These practices can best be supported when the following principles are used to guide development: ecological integrity, efficiency, equity, and integration-balance-harmony (Wall, 1993).

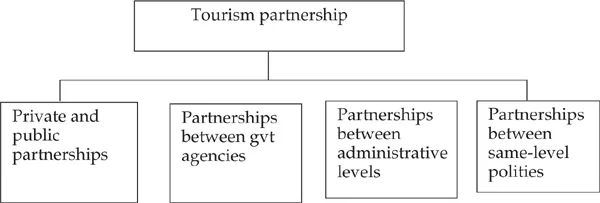

In areas where natural and cultural tourism resources lie across, or adjacent to, international boundaries, these principles of sustainability can be upheld better through cross-border partnerships. While the general cooperation and collaboration literature is vast, focusing on many forms of partnerships, Timothy (1998) identified four types that are most essential in the context of tourism planning (Figure 1). Private–public sector initiatives (including NGOs) are vital as the public sector depends on private investors to provide services and to finance the construction of tourist facilities. By the same token, private tourism projects require government approval, support, and infrastructure development. Cooperation between government agencies is essential if tourism is to develop and operate smoothly. Coordinated efforts between agencies decrease misunderstandings and conflicts related to overlapping goals and missions, and they help eliminate some degree of redundancy that exists when parallel, or duplicate, research and development projects by different agencies occur. Furthermore, to be successful, tourism development in a region usually requires coordinated efforts between two or more levels of administration (e.g. nation, state, province, district, county, municipality), particularly when each level is responsible for different elements of the tourism system. Finally, as mentioned above, partnerships between same-level polities are particularly important when natural and cultural resources lie across political boundaries. This can help prevent the over-utilisation or under-utilisation of resources and eliminate some of the economic, social, and environmental imbalances that commonly occur on opposite sides of a border (Timothy, 1998). In a global sense, international cross-border partnerships are perhaps the ultimate form of partnership because they require more careful planning and formalisation than linkages between authorities and private institutions within one country.

Figure 1 Types of partnerships in tourism (Source: After Timothy, 1998)

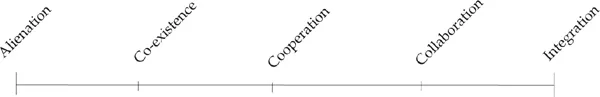

Martinez (1994: 3–4) introduced a four-part typology of cross-border interaction to assess human movement between adjacent countries. First, alienated borderlands are those where day-to-day communication and interaction are almost entirely absent. Second, coexistent borderlands are found where the frontier is slightly open to minimal levels of interaction. Third, interdependent borderlands are characterised by a willingness between adjacent countries to establish cross-frontier networks and partnerships. Fourth, integrated borderlands exist where all significant political and economic barriers have been abolished, resulting in the free flow of goods and people.

Borrowing from Martinez’s (1994) model, Figure 2 combines his alienation, coexistence, and integration elements with cooperation and collaboration to illustrate a five-part typology of levels of cross-border partnerships in tourism. Alienation means that no partnerships exist between contiguous nations. Political relations are so strained or cultural differences so vast that networking is not feasible or possible. Coexistence involves minimal levels of partnership. As the word denotes, neighbouring nations tolerate each other, or they coexist, without a great deal of harmony. They do not stand in the way of each other’s development, but do not actively work together to solve common problems. Cooperative partnerships are characterised by initial efforts between adjacent jurisdictions to solve common problems, particularly in terms of illegal migration and resource utilisation. Collaboration occurs in regions where binational relations are stable and joint efforts are well established. Partners actively seek to work together on development issues and agree to some degree of equity in their relationship. Finally, integrated partnerships are those that exist without boundary-related hindrances, and both regions are functionally merged. Each entity willingly waives a degree of its sovereignty in the name of mutual progress.

Figure 2 Levels of cross-border partnerships in tourism

While cooperation and collaboration are clearly important, not all outcomes are positive. Cross-border partnership is time-consuming and costly and often results in effects not commensurate with the efforts involved. In the case of fully integrated networks, some of the attractiveness of border resources may be dulled as they become too similar on both sides. Several scholars claim that contrasts in politics, economics, cultures, and landscapes are part of the tourist appeal in borderland attractions (Arreola & Curtis, 1993; Eriksson, 1979; Leimgruber, 1989). Furthermore, in some cases, cross-border coordination may lead to political opportunism and the reinforcement of existing power among a privileged few on one or both sides of the boundary (Church & Reid, 1996: 1299), which may result in more pronounced disparities between regional development outcomes (Scott, 1998).

Trans-frontier networks may also promote competition that is harmful to peripheral regions in that it creates rivalries between local authorities. This can ultimately result in destabilised cross-border relations (Church & Reid, 1996). Moreover, Scott (1998: 620) suggests that the formalisation of cross-border partnerships may encumber and lead to the bureaucratisation of certain processes instead of allowing them greater freedom to develop.

These criticisms notwithstanding, natural ecosystems and, in many cases, cultural areas are not restricted within human-created boundaries. When such resources overlap international frontiers, yet another twist is added to the already complex concept of sustainability. Thus, some degree of interjurisdictional networking is vital because it has the potential to reduce economic, social, and ecological imbalances that occur on opposite sides of a boundary (Kiy & Wirth, 1998) and will lead to more holistic and efficient planning as all parts of the attraction are considered as one, and the duplication of development projects may be eliminated (Timothy, 1998). Nonetheless, obstacles, such as immigration and customs restrictions, different languages, poor international relations, contrasting management regimes, and lack of authority of local administrators to make cross-boundary arrangements, may challenge, or even thwart, cooperative efforts (Blatter, 1997; Dupuy, 1982; Saint-Germain, 1995).

Administrative frameworks, infrastructure development, conservation, human resources, promotional efforts, and border concessions are of special interest to management personnel and planners in international parks because they are directly linked to contrasting political systems and issues of sovereignty. By working in concert with their cross-border affiliates, resource administrators can contribute to meeting the goals of sustainable tourism.

Special management frameworks that allow cross-frontier coordination while still respecting the sovereignty of each nation can be created. In most cases this is done by formal treaty. Funding and land ownership, as well as everyday operations, can be integrated into management systems that are appropriate for borderland locations.

Transportation standards can be upheld better with the internationalisation of infrastructure development and maintenance (Artibise, 1995). Open accessibility is hindered when governments do not collaborate on issues such as road construction, public services, and transportation. When this happens it is usually a result of the fact that national priorities tend to outweigh cross-national considerations (Naidu, 1988). Working together on matters of infrastructure can also eliminate or decrease inequitable access to shared resources (Ingram et al., 1994). Also, a lack of coordinated efforts to develop the infrastructure can result in costly and needless duplication of facilities (Gradus, 1994). By working jointly in areas of physical facilities planning, both parties can create similar conditions that will appeal to visitors and contribute to a sense of harmony and integration, as well as provide opportunities for more efficient production.

Partnerships also work wonders for conservation. A lack of cross-boundary cooperation can result in the over-exploitation of resources on one side of a border, which may create severe conservation problems for neighbouring regions (Timothy, 1998). Some species of animals, for example, may be protected in one jurisdiction but hunted for sport in a neighbouring jurisdiction. Since resources are not bound by political borders, many conservation problems cannot be solved without the involvement of administrators in both regimes. In an effort to promote ecological integrity, integration, balance, and harmony, transnational networking can help facilitate the standardisation of conservation regulations and controls on both sides of a border. This is especially important w...