![]()

1 Introduction

It could be, of course, that there was something more than mere physical appearance behind this. Alexander McCall Smith, Morality for Beautiful Girls (2002: 114)

Real Women, Real Lives, Real Language

‘Will you be my sponsor?’ With the solemnity of a priest, a beauty contestant uttered these words to me as she followed me home after my first visit to watch a pageant rehearsal. She sought money to re-enroll in secondary school, explaining that her small earnings from winning a lower-level pageant went to her family and that she still needed money to pay for delinquent school fees. Though certainly not my first encounter with structural inequality, it was the first time I really considered how these pageants could be about far more than the language ideologies I had initially set out to study. This contestant’s request made clear to me several things: that she was struggling with some hard realities; that she saw pageants as a way to better her life; that education seemed to be an answer to her troubles; and that she believed by looking at me that I had more than she did. Furthermore, her use of English with me was significant. Even though earlier she had only heard me speak Swahili as I introduced myself to the group and chatted with the pageant director, her choice of language clued me into a way of reckoning links between language value and personhood that extended beyond the strictly local setting of my study.

This book is as much about lives as it is about pageants. In particular, it is about average Tanzanians, mostly young women, living in cities, getting by but often just barely. Many reside with their families, some live on their own or with friends, and sustenance is almost always a collective effort. These women, though living in what for many people is an isolated corner of the world, consider themselves part of the world, interacting with products, ideas and ways of being in wide global circulation. In many cases, they live rather local lives, in the sense that they may infrequently leave their own neighborhood or city, let alone their own region or country, and may only rarely interact with people from far away. Yet, in pageants, they expertly mix second-hand clothing from the United States with inexpensive items from China or India into fashion-forward outfits; they are as likely to perform dance numbers to local Bongo Flava hip-hop music, or to South African pop diva Brenda Fassie, as to Beyoncé. They speak on stage about subjects such as HIV/AIDS which bridge local, regional and global concerns. Their language use in the competition is likewise reflective of their locality as well as of their place as citizens of the world.

In Tanzania, beauty pageants are wildly popular, with minute details of the contests and their participants appearing frequently in newspapers and other media. And while the media and individuals frequently condemn contestants, especially claiming their utovu wa nidhamu (‘lack of good behavior’) pageants remain a popular spectator sport, and contestants and winners often become, at least ephemerally, national celebrities. Nonetheless, finding qualified and willing contestants sometimes proves difficult. Newspaper advertisements appear during the weeks leading up to the preliminary pageants encouraging young women to submit applications, luring them with the promise of cash and other prizes; however, often this is not enough. Local pageant directors actively recruit girls, by going to their schools, and especially their homes, where parental resistance can be strong. In one case, a pageant director, herself a former Miss Tanzania and now a wife, mother and career woman, said she used her status and accomplishments to present herself to parents as a role model for their daughters. A confident, successful and articulate woman, yet one who embraces motherhood and her role as a wife, she sells pageants as a stepping stone to a prosperous, modern Tanzanian life.

In this way, the director emphasizes another part of the perceived experience of beauty queens – their ability to escape from life-as-usual in Tanzania. Young women who participate do so in part as a way to engage in an aesthetic cosmopolitanism, as well as in hopes of winning prizes, scholarships and money. In addition, many become involved for the opportunity to get out – of their town, of their lifestyle, of poverty or, even, of Tanzania. Newspapers remind their readers of the glamorous lives of former national beauty queens. Reports laud the successes of Miss Tanzania 1967, living in Germany, Miss Tanzania 1996, residing in Italy, and Miss Tanzania 1999, who pursued a degree in the United States. Others have achieved fame and fortune outside of their title as national beauty queen, such as Miss Tanzania 2000, Jacqueline Ntuyabaliwe, who became an East African pop music star performing under the name K-Lyinn. These stories help contestants imagine possibilities in their own lives that might arise out of competing in pageants. While many young women participate in pageants for fun, they also see them as one of their few means of escape, a route to a dream of securing an education and their independence, often perceived as possible only elsewhere.

So, despite the manifold ways in which young urban Tanzanian women tap into and integrate a wide array of locally sourced and international resources for aesthetic, practical and identity-making purposes, they are nonetheless sensitive to their particular place on the global periphery. Many hold ambitions of leaving where they are, for a bigger regional city, for the capital city, Dar es Salaam, for neighboring Kenya, for South Africa, for Dubai, for London or for the United States – anywhere where opportunity is seen as greater than where they are at the moment (which is almost everywhere). They seek independent, stylish and modern lives, away from paternal or conjugal authority, and English is often understood as a critical tool in fashioning their own, mobile, futures. Beauty pageants offer both an opportunity to engage in the aesthetics of globalization and a glimmer of hope for a new, prosperous and independent life.

When I first began studying language use in beauty pageants, years ago as part of my dissertation research, I was impressed by the fact that everyone at these events seemed to be having a lot of fun. Full of music, dance, fashion and humor, Tanzanian beauty pageants are truly a great time for everyone involved. Yet, as I continued researching them and maintained contact with my consultants and friends from my fieldwork, I started to recognize the ways in which pageants also provide a lens into the structuring and gendering of inequality in Tanzania. Language plays an important role, but so do other symbolic resources that are linked with language in terms of their acquisition and interpretation. At once a source of hope, disappointment and cosmopolitan creativity, pageants engage the imagination of many young women who see beauty queens as the kind of woman they strive to be.

To frame this study as concerning real people and life opportunities, I will begin with two vignettes. The first retells the fairy-tale life of the most successful Miss Tanzania in the institution’s history, a highly anomalous yet also salient story to the young women in this project for whom her life represents the potential that pageants – and very little else – offer them. The second vignette describes the life of Justina, a typical contestant, for whom the promise of pageantry failed to come through. Together, these stories frame what is possible, as well as what is probable, for the contestants in this study.

Happiness becomes Millen

Looking every bit the international beauty icon, Happiness Magese is tall and stunning, with long limbs and smooth, light-brown skin, shiny straight hair falling far down her back, and graceful, self-assured movement.1 In 2001, Happiness won the Miss Tanzania crown and has since become a national celebrity. At the time of her competing in the Miss Tanzania competition, she was an English-language university student specializing in law in Dar es Salaam. After winning the title (but not performing well at Miss World) and spending a few years in Tanzania seeking to turn her experience into a modeling career, Happiness earned her breakout job on the cover of Kenyan Cosmopolitan magazine. Soon thereafter she moved to South Africa, where she signed with a prominent modeling agency, changed her first name to ‘Millen’ and became a near-household name there. After gaining significant success on the African continent and in Europe doing print and runway work, she moved to New York in 2009 and signed with Ford Modeling Agency. She currently walks the runways of Paris, Milan and New York, and is, as is often noted, the only black face of Ralph Lauren.

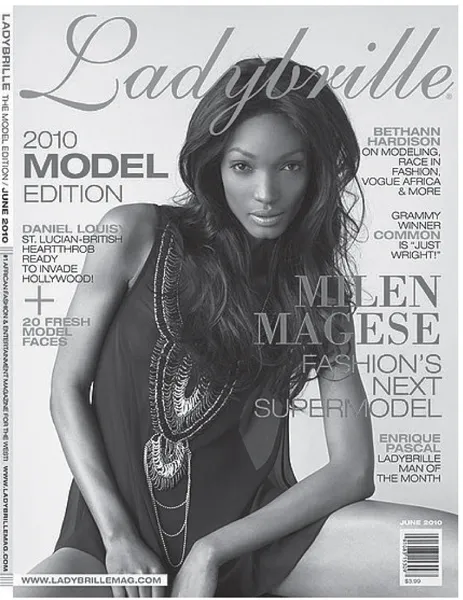

Figure 1.1 Millen (Happiness) Magese, Miss Tanzania 2001, on the cover of a pan-African fashion magazine. Note the variant spelling of ‘Milen’

This career trajectory is extremely unlikely for the young women in this study. Millen is the only Miss Tanzania winner2 to have done well as an international model, despite the fact that most young women see the events as a platform for just that. While several winners have secured other kinds of success within Tanzania, none has achieved the kind of mobile, global, cosmopolitan life that Millen has. As a product of her upbringing, her education and her career, she speaks a pan-African version of the standard English, at once full of exotic charm but also fully fluent. Her language thus serves both as an index of her success and as a tool for having achieved it. Even her name change signals a move from a local identity to a translocal one; while ‘Happiness’ is certainly an English word, it is not, outside of some African contexts, typically an English name. Changing her name to Millen marked, as well as ushered in, her new identity as a truly cosmopolitan, borderless, international beauty icon (Figure 1.1).

Justina

When I first met her, Justina lived with her mother and younger brother in a two-room wattle-and-daub house with a concrete floor in the northern city of Arusha. Adjacent was the one-room house of her older brother Charles, who had a new baby. While neither dwelling had running water, Charles’s had electricity and pirated cable television, on which Justina eagerly watched local and international music videos when time and unpredictable power delivery permitted. The families shared three goats and several chickens, which they kept in a corner of their courtyard, a cheerful space with potted plants dotting the edges of the swept dirt. Justina’s parents – divorced for many years – were ethnically Maasai, but, unlike her parents and older brother, she did not speak the language.

From the beginning, Justina struggled to raise enough money to stay in secondary school. She repeatedly had to drop out, because her mother, who earned a small living through her sewing and mending, did not have enough money for school fees. Sometimes, she could resume her schooling thanks to a windfall from Charles, who worked in the dangerous and largely uncontrolled tanzanite mines of the region. Charles would vanish for weeks at a time to work, then return to Arusha’s black market to sell whatever rough stones he had found, a process which yielded an unpredictable and barely sustaining income for his family. Finally, in the middle of her secondary education, Justina dropped out permanently. Now her younger brother was also secondary-school age, and the family thought it was important for him to have at least some higher education.

Justina worked during this time, helping her sister-in-law buying and reselling second-hand clothing. After several months, she enrolled in a local computer course thanks to another contribution from Charles. Upon completion of the course, Justina tried to obtain a job as a receptionist in several of the local hotels and tourism companies catering to the international safari clientele, a line of work in which she was very interested. However, potential employers repeatedly turned her away due to her poor English skills. It was at this point, at the age of 18, that Justina enrolled in a local beauty pageant. She liked the idea of performing in the contemporary dance routines, as well as wearing a fancy evening gown and high-heeled shoes for the first time. Even more captivating to her, scholarships were available to a local tourism school, and cash was also among the prizes.

While Justina finished in the top three in the city-level pageant, she failed to gain a place in the regional pageant (again, her language and communication skills may have, in part, been at issue here, though so were her brown-stained teeth, a result of fluorosis from high fluoride levels in water, common in the region). Disappointed, she used her small pageant earnings, as well as help from a family friend, to enroll in a travel and tourism school in downtown Arusha. Here, she took half-day classes for four months, on the subjects of airline ticketing, accounting and English. Justina graduated from the program with honors, and her school arranged an internship for her with a mid-range tourist hotel in central Dar es Salaam. When she arrived, however, the hotel manager put her to work as a cleaning woman rather than as a receptionist, again because of her inadequate English. Justina stayed at the hotel for two months, until she contracted malaria and had to return to her family in Arusha for recovery;3 since she was too ill to work, she could not afford her housing in the capital. Pending another big find by her brother, she planned to attend an English school across the border in Nairobi, where she believed language teachers would be more qualified.

Together, the life stories of Millen and Justina serve as an instructive starting point for this book. Millen’s career trajectory is the fantasy for many young Tanzanian women who participate in pageants and who have followed Millen’s movements in newspapers since her name was still ‘Happiness’. Justina’s life, on the other hand, is typical of the struggles of many young urban women in Tanzania to survive, be independent and find some enjoyment and meaning in life. Her participation in pageants was at once a pleasurable engagement with contemporary fashion and beauty as well as an ambitious attempt at escape. Both women participate – through pageants, clothing, media and travel – in a globalized world, yet they do so in extremely different ways, which belie stark inequalities in Tanzania. The pageants that gave Justina hope for escape and Millen a bona fide career as an international fashion model offer a glimpse into the forces that shape urban Tanzanian lives, as both a part of and on the fringes of our interconnected world.

Pageants as Global and Local

While contests of feminine beauty of one kind or another have been around for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, with precursors for example in ancient Greece (Pomeroy, 1975) and medieval England (Banner, 1983), the modern beauty pageant has its most direct lineage in the past century or so in the United States. It was in 1921 that beauty pageants really took off, with the introduction of the Miss America competition in Atlantic City, New Jersey (Ballerino Cohen et al., 1996b). Soon after the original Miss America4 contest, similar beauty pageants started to appear outside of the United States, and in the years following World War II they became a truly global phenomenon. England, where Queens of May contests already had a long history, was the quickest to catch on (Synnott, 1989). However, it did not take long for France, Turkey and other nations, including newly independent African countries such as Tanzania, to begin hosting their own national beauty pageants, where it is likely the spirit of nationalism fostered their spread (Ballerino Cohen et al., 1996b). Indeed, pageants worldwide began to embrace the contests as showcases for patriotism, citizenship and scholarship, and it is these ideals which remain largely the image that national beauty pageant enterprises tend to circulate today (Ballerino Cohen et al., 1996b; Deford, 1971).

Regardless, however, of the meanings promulgated by the pageant industry, citizens, participants and critics make their own sense of these spectacles. Today in the United States, for example, pageants are often loved as kitsch entertainment, disregarded as frivolous pop culture or embraced, typically by those involved, as scholarship opportunities and career stepping-stones (Banet-Weiser, 1999). American feminists have focused for decades on pageants as degrading and alienating, while post-feminists such as Camille Paglia and Naomi Wolf have stressed the agency of women who participate in such events (see overview in Banet-Weiser, 1999).

Yet these understandings do not find much traction in other parts of the globe, where the existence of pageants often signals emergent personae and positionalities vis-à-vis others, perceived as more ‘traditional’. It has been argued that ‘beauty contests are places where cultural meanings are produced, consumed, and rejected, where local, global, ethnic and national, national and international cultures and structures of power are engaged in their most trivial but vital aspects’ (Ballerino Cohen et al., 1996b: 8). While often self-consciously modeling themselves on Western, particularly American beauty pageants, the contests vary greatly: in the ways in which beauty is manifested; in discourses about femininity, authenticity and culture; and how local hierarchies of value and goodness are determined, displayed and disputed on pageant stages. These meanings are made visible not only through language but also through elements of feminine beauty, fashion, grooming and more.

While pageants are always necessarily made local, they are also often, simultaneously, felt as a cultural borrowing from the West. In many cases, pageants serve as an emblem of modernity, progress and cosmopolitanism (Besnier, 2002; Borland, 1996; Dewey, 2008; Johnson, 1996; Schulz, 2000). Through bodily adornment, shaping and carriage, contestants self-consciously mark themselves as knowledgeable of Western norms in fashion and styling. And it is not just the contestants themselves who bear such indexicalities. Pageants frequently take place in a city’s most up-to-date performance facility, and the entire spectacle of lights, dance, music and talk together allows audiences to participate in the performance of a modern, translocal, cosmopolitan sensibility. For others, however, a deep sense that pageants are indeed foreign produces debate, tension and controversy over the extent to which they are a harbinger of irrevocable changes in local norms and values (see Chapter 3).

Language and Globalization

Homogenization, hybridity or multivocality?

The spread of pageants worldwide (Ballerino Cohen et al., 1996a) is a clear example of the complex set of phenomena that is commonly understood as globalization. Coupland (2010: 1) discusses the now widely accepted claim that, ‘whatever globalization is, it isn’t an altogether new phenomenon’. The movements of people, products, money and ideas that help characterize globalizing phenomena...