![]()

1 Introduction

Introducing Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Instructional Pragmatics

Aim and scope of the book

The purpose of this book is to construct a framework for second language (L2)1 instructional pragmatics that is grounded in Vygotskian cultural-historical psychology, most often referred to in applied linguistics and L2 acquisition (SLA) research as sociocultural theory (SCT) of mind (see Lantolf & Thorne, 2006). Vygotskian SCT provides a powerful theoretical account of human development that recognizes the central importance of social relationships and culturally constructed artifacts in transforming biologically endowed psychological capacities into uniquely human forms of mental activity. From the perspective of SCT, the sociocultural domain is not merely a set of factors that trigger innate developmental processes within the mind/brain of the individual. Instead, it is the primary source, and principal driver, of mental development. When extended to formal schooling, including L2 education, such an orientation to human psychology compels us to engage in educational praxis wherein instruction drives development rather than following an assumed progression of innate developmental stages. As Vygotsky (1978: 89) forcefully argued, the only good instruction ‘is that which is ahead of development’.

Although this book is about the teaching of L2 pragmatics, it is not intended to present a set of teaching techniques or tips from which one can pick and choose at will. Instead, it aims to illustrate a coherent, systematic pedagogical program based on the principles of SCT. This not only includes recommendations for materials design and teaching practices, but also – and more importantly – a reconceptualization of the object of instructional pragmatics. Teachers will certainly find the book useful, and the data excerpts analyzed throughout are intended to show how an SCT approach to instructional pragmatics works in practice. Teachers are also encouraged to think about ways of adapting the pedagogical framework to suit their own needs and to work within institutional constraints. However, the reader should bear in mind that the pedagogical recommendations assume a particular perspective on the nature of language, pragmatics, mental development, and so on, that is derived from SCT. It is therefore necessary to understand the theoretical framework in order to appreciate the developmental significance of the specific pedagogical practices illustrated in this book. The chapters – whose contents are described at the end of this introduction – are organized with the aim of leading the reader through the components of the theoretical framework, using empirical data to illustrate the aspects of the theory under discussion as they apply to L2 instructional pragmatics.

The data used in this book were collected as part of a study of US university learners of French who participated in a pedagogical enrichment program that was designed to incorporate Vygotskian principles into L2 instructional pragmatics (more details are provided below). Although the data deal exclusively with French, the study serves to illustrate the principles and components of an SCT framework for instructional pragmatics. The framework can certainly be adapted for use in the teaching of any other language.

Defining pragmatics

The focus of pragmatics is on the way people accomplish actions through language. For example, a common area of inquiry examines the realization of speech acts such as invitations, apologies and requests. Inviting someone to a party, apologizing for being late, and requesting to borrow a book are all actions that can be – and are more often than not – accomplished at least in part through written or spoken language. Other actions accomplished through (or at least fundamentally shaped by) language include problem-solving, teaching, reflecting particular world views, creating and maintaining interpersonal relationships, performing social-relational roles and identities, and so on. How these actions are accomplished – that is, the language choices made by speakers – and their effects on other people are in turn subject to various communicative constraints and affordances. In this respect, Crystal (1997) offers a useful definition of pragmatics as a user-centered perspective on language-in-use.

[Pragmatics is] the study of language from the perspective of users, especially of the choices they make, the constraints they encounter in using language in social interaction and the effects their use of language has on other participants in the act of communication. (Crystal, 1997: 301)

Crystal’s definition is particularly well suited for research into L2 pragmatics because it allows for any instance of language use, learning and development to be studied from the perspective of pragmatics (Kasper & Rose, 2002). It follows that, with regard to L2 instructional pragmatics, any feature of discourse can be taught as pragmatics as long as the focus of pedagogy remains on language users’ choices, constraints and effects of language use during communication.

From the perspective of SCT, the ability to accomplish actions through language is mediated by the sociocultural resources available to a person. Mediation refers to Vygotsky’s (1978) proposal that higher forms of human cognition are accomplished through the integration of cultural tools, including language, cultural scripts and concepts. These resources – or mediational means – include language forms as well as a person’s knowledge of which forms may or may not be appropriate for a given speech event. Also relevant here is Leech’s (1983) and Thomas’s (1983) now-classic bifurcation of pragmatics into pragmalinguistics – the intersection of pragmatics and grammar – and sociopragmatics – the intersection of pragmatics and culture. Both pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic knowledge mediate social action.

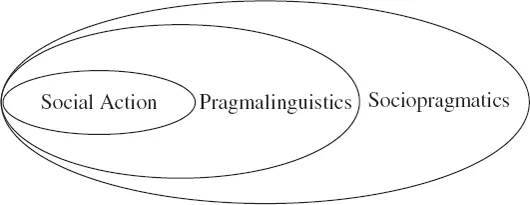

Pragmalinguistics entails knowledge of the conventional linguistic means through which social actions can be accomplished (e.g. the various ways of requesting the loan of something such as Give me that book versus Could I borrow that book? versus I was wondering, if it isn’t too much of a bother, whether you might consider loaning me that book, just for a little while). In this way, pragmalinguistics encompasses the conventional linguistic tools used to mediate social action. However, speakers do not simply use any and all pragmalinguistic resources randomly or inconsequentially. Instead, sociopragmatic knowledge intervenes to mediate the choices speakers make from among these pragmalinguistic resources in light of present goals for the course of action and potentially changing circumstances. Sociopragmatic knowledge involves an understanding of the conventions of ‘proper’ or ‘appropriate’ social behavior, including what to say to whom and when, as well as an understanding of the social consequences of conforming to or breaking those conventions (see Chapter 2). In short, sociopragmatic knowledge mediates the choices speakers make in implementing the available pragmalinguistic resources in the accomplishment of social action. This relationship is depicted in Figure 1.1 as three interlocking ovals. Social actions are goals to be accomplished (e.g. inviting someone to dinner), and these actions are mediated by the means available to speakers (pragmalinguistics), the selection of which is in turn mediated by speakers’ knowledge of sociocultural schemas, concepts and social relations (sociopragmatics).

Figure 1.1 Interwoven nature of social action, pragmalinguistics, and sociopragmatics

In sum, mediation lies at the center of a sociocultural conceptualization of pragmatics. Social actions, pragmalinguistics and sociopragmatics are interwoven facets of goal-directed activity. As language users, we employ linguistic resources with an objective in mind, and we use our knowledge of sociocultural schemas to choose the resources that can be used to achieve our goals the way we want to achieve them. While this view certainly includes conventional patterns of meaning and language use, the emphasis on agentive language use leaves open the possibility that the way in which we want to accomplish a given goal may break social conventions. In other words, we can choose to conform to or reject conventions of appropriate social behavior because we know what the consequences of doing one thing or another may be given present circumstances. It is this information – clear, systematic sociocultural schemas – that is often missing from L2 pragmatics instruction.

Teaching pragmatics

Research inspired by Kasper’s (1997) call for investigations into the teachability and learnability of L2 pragmalinguistics and sociopragmatics has suggested that classroom learners do indeed benefit from some form of instruction. (Thorough reviews are provided in Alcón Soler & MartínezFlor, 2008; Ishihara, 2010; Kasper, 2001; Kasper & Roever, 2005; Kasper & Rose, 2002; Martínez-Flor & Usó-Juan, 2010; Rose, 2005; Rose & Kasper, 2001; Taguchi, 2011; Takahashi, 2010.) Yet this research has yielded mixed findings regarding the efficacy of implicit versus explicit approaches to teaching. In some cases, implicit conditions – which involve the provision of positive evidence of pragmatic forms and corrective feedback on infelicitous learner language – appear to be as beneficial as explicit instruction in developing pragmalinguistic knowledge. However, the literature suggests that explicit instruction in which metapragmatic information is provided is more beneficial than implicit instruction in developing sociopragmatic knowledge (Takahashi, 2010). Sociopragmatic information, it seems, is more difficult for learners to deduce from positive evidence than is pragmalinguistic form. As such, some explicit intervention is helpful in drawing learners’ attention to sociopragmatics.

As noted above, explicit instructional conditions provide metapragmatic information about the various forms being taught, including judgments of politeness and formality. In this way, SCT partially aligns with non-SCT research into instructional pragmatics that privileges explicit instruction because sociopragmatic knowledge is argued to mediate pragmatic action. However, the SCT framework diverges from more traditional approaches in how it conceptualizes the object of explicit instruction. In traditional approaches to instructional pragmatics, metapragmatic information is typically presented as a set of doctrinal, norm-referenced rules of thumb, or what van Compernolle and Williams (2012c: 185) refer to as ‘narrowly empirical representations’ of conventions (see also van Compernolle, 2010a, 2011b), that provide learners with little information about the meaning potential of the linguistic forms they are acquiring and are, in at least some cases, inaccurate. Instead, the SCT framework compels us to design coherent concept-based instructional materials in order to mediate learner development (see the discussion of systemic-theoretical instruction, below). A similar critique has been leveled against mainstream instructed SLA research, where the grammatical rules presented to students are often unsystematic and fraught with exceptions, ambiguities and inaccuracies (Lantolf, 2007).

One representative example of the unsystematicity of traditional approaches to instructional pragmatics is illustrated in Martínez-Flor and Usó-Juan’s (2006) ‘6Rs’ framework. Their recommendations are intended to assist L2 English learners in developing their pragmatic abilities in the speech acts of requesting and suggesting and ‘to gradually make learners pay attention to the importance of the contextual and sociopragmatic factors that affect which of the two speech acts has to be made and how’ (Martínez-Flor & Usó-Juan, 2006: 44). The approach begins by introducing learners to two important issues in pragmatics: first, the difference – and relationship – between pragmalinguistics and sociopragmatics (following Rose, 1999); and, second, the three central social variables presented in politeness theory (Brown & Levinson, 1987) – that is, social distance, power and degree of imposition. Martínez-Flor and Usó-Juan provide explanations and examples of these factors and their effect on politeness in language (see Table 1.1) as a teacher’s guide to discussing sociopragmatic factors with their students. Although this orientation to teaching pragmatics is interesting, and on the surface appears to articulate with the SCT framework presented in this book (i.e. teaching concepts), there are two fundamental problems with the way in which social distance, power and degree of imposition are supposed to be explained to learners.

Table 1.1 Sociopragmatic factors

Explanation of factors for teachers | Effect on level of politeness |

Social distance ‘refers to the degree of familiarity that exists between the speakers (e.g. Travel Agent – Customer, do they know each other?)’ (p. 58) | Politeness increases with degree of social distance |

Power ‘refers to the relative power of a speaker with respect to the hearer (e.g. Hotel Manager – Receptionist, rank within a company)’ (p. 58) | Politeness increases with degree of power difference |

Imposition ‘refers to the type of imposition the speaker is forcing someone to do (e.g. to borrow money versus to borrow a pen)’ (p. 58) | Politeness increases with degree of imposition |

Source: Adapted from Martínez-Flor & Usó-Juan, 2006

First, these three social variables are represented as static and preexisting the communicative context. Consequently, language use (i.e. the selection of pragmatic forms) is represented as reactive with no mention of the ways in which the qualities of social relationships (i.e. social distance and power) are created through language. Likewise, the explanation of imposition suggests that specific request and suggestion types always impose on the hearer in the same way. For instance, it is implied that borrowing money is always a great imposition while borrowing a pen is not, regardless of the context of the request. This certainly cannot be the case, since asking a classmate if one may borrow his or her only pen during an exam would be a much greater imposition than asking a good friend if one might borrow some change to buy a drink from a vending machine. It should also be noted that the explanations are generally vague. For example, the terms power and imposition are actually used to define the concepts of power and imposition. These definitions, therefore, can have very little explanatory value.

Second, the chart misrepresents the relationship between the three social variables and politeness. On the one hand, the concept of politeness as construed by Brown and Levinson (1987) is not explained, and there is no mention of the notion of face or ...