![]()

Part 1

General Considerations for L2 Assessment

![]()

2 Oral Fluency and Spoken Proficiency: Considerations for Research and Testing

Heather Hilton

The titles of this volume and this chapter contain the word proficiency, a somewhat treacherous concept in the contemporary world of second language (L2) teaching methodology (and a notoriously difficult word to translate). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the Latin etymon of the adjective proficient has the meaning of going forward, making progress. The first definition given is ‘Going forward or advancing towards perfection’, and the second is ‘Advanced in the acquirement of some kind of skill; skilled, expert’ (1971: 2317). Yet this idea of expertise is at odds with current European texts defining a ‘plurilingual’ policy for language teaching and assessment:

[T]he aim of language education is […] no longer seen as simply to achieve ‘mastery’ of one or two, or even three languages, […] with the ‘ideal native speaker’ as the ultimate model. Instead, the aim is to develop a linguistic repertory, in which all linguistic abilities have a place. (Council of Europe, 2000: 5)

In a similar generalizing vein, the American Council of Teachers of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) – one of the first organizations to implement wide-scale oral proficiency testing in the wake of the Communicative movement in language teaching back in the 1980s – has recently altered its definition of oral proficiency from ‘the ability to accomplish linguistic tasks’ (ACTFL, 1999: 1) to the broader ‘functional language ability’ (ACTFL, 2012: 3).

A vast amount of experimental and applied research has been devoted to exploring exactly what ‘functional language ability’ actually consists of, and how a teacher, an examiner or a researcher can describe or identify varying levels of this ability. Most of it tends to equate ‘proficiency’ with ability to produce spoken or written language, and unfortunately neglecting the more reliably measured ability to comprehend spoken language as a robust proficiency indicator (Feyten, 1991; see also the chapters by Zoghlami and Prince in this volume for a detailed presentation of the construct of listening comprehension). For reasons linked to the epistemology of language acquisition research (emerging from applied linguistics, Hilton, 2011a), much of this work on productive proficiency has focused on the morphosyntactic and discursive characteristics of foreign-language speech and writing (Hulstijn, 2010: 236; see McManus et al., this volume), with a recent shift of scientific interest towards the lexical, phraseological and phonological components of proficient expression. This chapter will be devoted to an inventory of the characteristics of oral production in a parallel corpus of native and non-native speech in French and English. Following two recent models of L2 production (Kormos, 2006; Segalowitz, 2010), I will be considering ‘functional language ability’ more from a language processing perspective than a linguistic or acquisitional point of view. Online language-processing experiments rarely deal with spoken language at a discursive level, and L2 oral corpora have rarely been examined as illustrations of processing phenomena.1 The point of this chapter is to see what careful analysis of real-time speech by speakers of differing ‘language ability’ can contribute to the on-going proficiency debate, and more specifically to the reliable evaluation of spoken production.

Current L2 Production Models

Two interesting books have recently attempted to augment and update the famous ‘blueprint for speaking’ developed by psycholinguist Willem Levelt during the 1990s (Levelt, 1989, 1999): Judit Kormos’ (2006) Speech Production and Second Language Acquisition and Norman Segalowitz’s (2010) Cognitive Bases of Second Language Fluency. As their titles indicate, both books examine the particularities of second- or foreign-language speech production, using Levelt’s meticulously documented first language (L1) model as their starting point. The book titles also indicate the different focus adopted by each author: Segalowitz considers fluency, a ‘multidimensional construct’ (2010: 7) that is a sub-component (or indicator) of overall speaking proficiency, whereas Kormos explores all aspects of L2 speech production, including fluency. Both Kormos and Segalowitz avoid the pedagogically unfashionable etymological nuances of the word ‘proficiency’ by adopting (respectively) the more generic term ‘production’ or focusing on the more limited ‘fluency’ construct. Oral production can be at any level of expertise; this is one of the four basic language skills, the one we spend about 30% of our L1 processing time engaged in (Feyten, 1991: 174). The adjective fluent is often used in conversational English as a synonym of proficient, but the notion of fluency has taken on a more restricted meaning in the field of language acquisition research, referring to the temporal characteristics of spoken discourse (speech rate, hesitation rates, numbers of words or syllables between pauses, and so on; for overviews, see Griffiths, 1991; Kaponen & Riggenbach, 2000; Lennon, 1990; and especially Segalowitz, 2010: Ch. 2). The prevalence of the term fluency in recent second language acquisition (SLA) research illustrates a scientific interest in objective, quantifiable – and therefore reliable – indicators of oral performance (Segalowitz, 2010: 31); this preoccupation should not be mistaken for a reductionist view of language proficiency. Temporal characteristics – and more precisely various hesitation phenomena (silent and filled pauses, stutters, repetitions and repairs) – are seen as important keys to understanding the complex processes (pragmatic, cognitive and linguistic) that make L2 communication possible. Fluency is ‘a performance phenomenon’ (Kormos, 2006: 155); fluency indicators would be those that reliably reveal ‘how efficiently the speaker is able to mobilize and temporally integrate, in a nearly simultaneous way, the underlying processes of planning and assembling an utterance in order to perform a communicatively acceptable speech act’ (Segalowitz, 2010: 47).

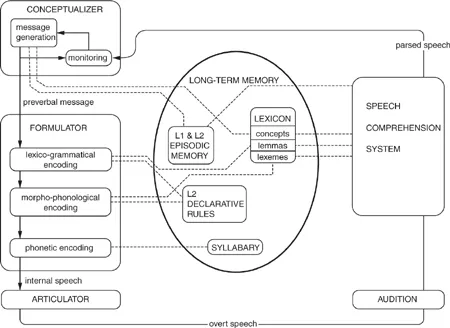

As cognitive and social psychology advance, psycholinguistic models become more and more complex, and Kormos’ ‘model of bilingual speech production’ (2006: 168; reproduced in Figure 2.1) is no exception. Those familiar with Levelt’s ‘blueprint’ will recognize the three experimentally established ‘encoding modules’ (on the left of the diagram) that interact in cascading fashion in L1 production – the conceptualizer (which generates a ‘preverbal message’), the formulator (which ‘encodes’ this message in words and phrases) and the articulator (which prepares the motor processes involved in uttering the message). These are fed by knowledge and procedures stored in a speaker’s long-term memory, at the center of the diagram (De Jong et al., 2012: 10–11; Kormos, 2006: 166–167). The particularities of L2 production are reflected by a set of ‘L2 declarative rules’ that have been added to the long-term store: these are the not-yet automatized ‘syntactic and phonological rules’ that much L2 classroom time is devoted to describing (Kormos, 2006: 167). It is a pity that this model does not illustrate more clearly an important difference between the L1 and L2 lexical store, which Kormos clearly develops in her eighth chapter – that is, the fact that much of the language manipulated in L1 speech is composed of plurilexical ‘formulaic sequences’ (Erman & Warren, 2000; Sinclair, 1991; Wray, 2000, 2002), whereas less-proficient L2 production involves the conscious2 arrangement of individual lexemes into syntactic units, a concerted, serial process that is qualitatively different from highly automatized L1 speech (Kormos, 2006: 166). Segalowitz develops similar themes in his consideration of L2 fluency; his model also situates Levelt’s ‘cognitive-perceptual’ modules within a larger system that includes the social and personal aspects of language processing, such as motivation to communicate, personal experience, and interactive context (Segalowitz, 2010: 21, 131).

Figure 2.1 Kormos’ ‘model of bilingual speech production’ (Kormos, 2006: 168)

Using Kormos’ model as its theoretical framework, the next section of this chapter will look more closely at temporal features of L2 speech, and the characteristics of temporally fluent and less-fluent productions. It is hoped that by considering temporal features of productive fluency, and by examining the linguistic and discursive phenomena observed at different, objectively identifiable fluency levels, we can come to a clearer understanding of just what makes a speaker proficient.

Analysis of the PAROLE Corpus

Corpus design

As more extensively reported elsewhere (Hilton, 2009, 2011b; Osborne, 2011), the Corpus PARallèle Oral en Langue Etrangère (PAROLE Corpus) compiled at the Université de Savoie in Chambéry, France (Hilton et al., 2008), is a relatively classic learner corpus (young adults carrying out quasi-monological descriptive tasks in either L2 English or French). The 45 subjects (33 learners of English and 12 learners of French) were recruited as paid volunteers from groups hypothesized to have different overall proficiency levels: first-year language or business majors, compared with students in a Master’s program preparing for a competitive foreign-language teaching qualification. Spoken proficiency was not measured prior to the project, but each subject completed a series of complementary tests and questionnaires, providing further information on L2 listening level, lexical and grammatical knowledge, as well as motivation for L2 learning, grammatical inferencing ability, phonological memory and linguistic profile (Hilton, 2008c: 8–10). The actual productions in the English L2 sub-corpus were evaluated by two expert raters, who determined each learner’s European reference level for both fluency and overall speaking proficiency (Council of Europe, 2000: 28–29); inter-rater reliability was high for these criterion-referenced judgments of oral performance (Spearman rank correlation coefficients of 0.84 for fluency and 0.73 for overall speaking proficiency).

PAROLE was originally designed for linguistic analysis (morpho-syntactic and lexical characteristics of L2 speech) within the conventions of the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES, MacWhinney, 2007), but the research team rapidly became interested in the temporal characteristics of the L2 speech samples obtained, and during the transcription process all hesitations of over 200 ms were timed and carefully coded (Hilton, 2009). In order to obtain L1 fluency values for comparison, 17 native speakers (NSs) of the project languages (nine English, eight French) performing the same tasks were recorded, and these productions were also transcribed and coded. The findings presented here are compiled from two summary tasks (describing short video sequences immediately after viewing, with minimal intervention from the interviewer). The L2 subset of the corpus totals 9087 words (1 hour and 15 minutes), and the L1 subset 3732 words (22 minutes). According to the transcription conventions developed for CHILDES, an utterance in PAROLE is defined as an independent clause and all its dependent clauses (basically, a T-unit); all errors, stutters, drawls and retracings, as well as silent and filled pauses and other hesitation phenomena, have been coded conventionally, with a few project-specific adaptations. We are fully aware of the limitations of the T-unit as the basis for spoken discourse analysis (Foster et al., 2000), but in order to take advantage of the various programs developed for the CLAN (Computerized Language ANalysis) component of CHILDES, we were obliged to structure our transcriptions in this traditional way. In addition to the reliable tagging programs available in CLAN for the project languages, we were interested in the programs for lexical analysis (the useful ‘D’ statistic of lexical diversity, the automatic generation of regular and lemmatized frequency lists), the automated calculations of mean length of utterance and total speaker talking time, as well as classic search possibilities (for any string or coded element). The timing and coding of hesitations (silent and filled pauses) is relatively easy in the ‘sonic mode’ of CLAN, but further calculations of hesitation time values are relatively laborious, involving importing the results of symbol searches into a spreadsheet, and manipulating them to obtain totals, task by task. Information on hesitation times is, however, the key to quantifying fluency features in the speaker’s productions, and this process enabled us to calculate measures including mean length of hesitation, hesitation rates (per utterance, per 1000 words), the percentage of speaking time spent in hesitation, and mean length of run (MLR, the number of words between two hesitations). Speech rate (measured as words per minute) was also calculated, based on totals easily obtained in CLAN: total speaker talking time, total number of words produced, including (‘unpruned’) or excluding (‘pruned’) retracings and L1 words.

As in any corpus project, we found it necessary to clarify the criteria used to define various speech phenomena, and notably the typology used to code errors, hesitations and retracings (for full detail, see Hilton, 2008c). Five general error categories were coded: phonological, lexical, morphological, syntactic and referential. Four different types of retracing were coded: simple repetitions, reformulations (in which only one element of the repeated material has been changed), restarts (more than one element changed) and false starts (utterance abandoned; these last two categories were collapsed into a single ‘restart’ category for statistical analysis). Raw numbers of retracings and errors were converted to rate of retracing and error (per 1000 words). All silent or filled pauses of 200 milliseconds or more (Butterworth, 1980: 156) were timed and coded in PAROLE, and sequences of silent and filled pauses occurring between two words (or attempted words) were timed as a single ‘hesitation group’ (see Hilton, 2009, for details; Roberts & Kirsner, 2000: 137; see Campione & Véronis, 2004, for a similar treatment of hesitation sequences). The position of every hesitation (isolated pauses or hesitation groups) was manually coded according to three possible locations: at an utterance boundary, a clause boundary or within a clause.

Other non-temporal characteristics of the subjects’ productions were ...