![]()

Part 1

Language Use and Policy in the International Context

![]()

1 | English in Scandinavia: Monster or Mate? Sweden as a Case Study Catrin Norrby |

Introduction

When Swedish Crown Princess Victoria and Prince Daniel recently became parents, the prince explained his feelings at a press conference, hours after their daughter was born, with the following words (cited from Svenska Dagbladet, 23 February 2012):

Mina känslor är lite all over the place. När jag gick från rummet så låg den lilla prinsessan på sin moders bröst och såg ut att ha det väldigt mysigt

[My feelings are a bit all over the place. When I left the room the little princess was lying on her mother’s breast and seemed to be very cosy]

The use of English catchphrases and idioms in an otherwise Swedish language frame is not unusual and it is no exaggeration to say that English plays a significant role in contemporary Scandinavia. The following areas of use at least can be distinguished: (1) English taught as a school subject; (2) English used as a lingua franca; (3) English in certain domains; (4) English as an act of identity; and (5) English in the linguistic landscape.

The term ‘Scandinavia’ is used in this chapter as shorthand for Denmark, Norway and Sweden (where Scandinavian languages are spoken) as well as for Finland (which is part of the Scandinavian peninsula together with Sweden and Norway). English is taught as a mandatory subject in schools throughout Scandinavia, usually from Grade 3 or 4, meaning that school leavers normally have 9–10 years of English teaching. In recent years there has been an increase of CLIL (content and language integrated learning), where content subjects are taught in English (see, for example, Washburn, 1997). The availability of English instruction throughout the education system is a prerequisite for the generally high level of proficiency in English among Scandinavians (see below).

English is used as a lingua franca by Scandinavians for communication not only in international contexts but also nationally, as well as for inter-Scandinavian communication. Danish, Norwegian and Swedish are often taken as examples of mutually intelligible languages, enabling speakers to use their native language in communication with their neighbours, sometimes referred to as semicommunication (Haugen, 1972). Recent studies, however, indicate that mutual intelligibility might be diminishing, as adolescents generally understand English better, and also display poorer understanding of the neighbour languages compared to their parents (Delsing & Lundin Åkesson, 2005). Turning to the national level, English is also used for communication within many domains, in particular in research and higher education, business and large companies, as well as in popular culture and advertising. In this chapter, the focus is on the domains of research and higher education.

In Scandinavia, code-switching between a national language and English is a phenomenon which has been particularly observed in young people’s discourse. For example, Sharp (2001) found on average one code-switch to English per minute among Swedish youths. Most of these code-switches were unintegrated English language material in an otherwise Swedish frame, and were often made up of phrases from films, songs, advertising, and so on. Sharp (2001: 117) refers to these switches as ‘the quoting game’, where the speakers flag the shift to English by a change of voice quality or laughter. In other words, these code-switches can be interpreted as an act of identity where the speaker appeals to shared knowledge of global trends and in-group commonalities (see also Preisler, 2003 for similar results in a Danish context).

English in the linguistic landscape refers to the documentation of visible signs of English language use in a society, e.g. linguistic objects such as signs in the streets, in shops and service institutions. An important underpinning of linguistic landscaping is the understanding that public spaces are symbolically constructed by linguistic means (Ben-Rafael et al., 2010). In this chapter, we explore the extent of English presence in a large shopping mall in downtown Stockholm.

The points above are not discrete but overlapping categories. For example, use of English as a lingua franca clearly overlaps with its use in certain domains, and English as an act of identity encompasses not only spontaneous use in interaction: its use in the linguistic landscape can also often be interpreted as promoting a certain identity. Furthermore, the various points refer to practices at different levels in society. Some can best be described as forces from above (e.g. English in the education system, and in the domains of business or research) whereas others pertain to forces from below, at the grass-roots level (e.g. in private interactions, use in certain subcultures and music scenes). It has been argued that this combination of movements from both above and below accounts for the strong position English enjoys in Scandinavia (Preisler, 2003).

English Language Skills and Attitudes to English Among Scandinavians

In this section, the general level of English skills and attitudes to English among the Scandinavian population are outlined and compared to those of other Europeans.

Skills and attitudes among high-school students

In a study of English skills and attitudes among Grade 9 students in eight European countries – The Assessment of Pupils’ Skills in English in Eight European Countries (Bonnet, 2002) – student results from Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, France and Spain were compared. The results were based on a random sample of 1500 students from each nation (with the exception of Germany where the sample was much smaller and therefore not included in the overview below). The test was the same for all countries, but with instructions in the national languages. It was part of a survey of foreign language skills carried out on behalf of the European network of policy makers for the evaluation of education systems. Four skills areas were tested through multiple-choice and gap-fills: listening and reading comprehension, language correctness and written production. Students were also asked to evaluate the level of difficulty of the test and to assess their own English skills. In addition to the test and self-evaluations, both students and their teachers were asked about their use of and attitudes to English.

The results for each skills area can be divided into three tiers, where the Scandinavian (including Finnish) students tend to appear to the left, with higher skills, whereas the southern Europeans appear to the right, with lower skills. Norway and Sweden appear in the top tier for all four skills, and for reading and correctness we also find Finland among the top performers, as outlined in Table 1.1.

The strong results for the Scandinavian students can no doubt be linked, in part, to their positive attitudes towards English. The highest scores in this regard were recorded for the Swedish students, where 96% claimed to like English in general, followed by Denmark (90.2%), Finland (89.6%) and Norway (88.8%), compared with an overall average of 79.9% for the seven countries. As many as 98% of the Swedish students said it was important to know English, again followed by the other Scandinavians: Denmark (96%), Finland (92.7%) and Norway (91.6%).

Table 1.1 English skills among Grade 9 students in seven European countries

The positive attitudes among the Swedish high-school students support earlier research results, which have shown that Swedes in general are very well disposed towards English (Oakes, 2001; Wingstedt, 1998), and this observation is particularly true of younger generations. For example, in his comparative study on language and national identity in France and Sweden, Oakes (2001) found that young Swedes reported much more positive attitudes towards English than their French counterparts. They even rated English as more adapted to modern society and as more beautiful than Swedish. Such attitudes also work in tandem with perceived skills and Oakes suggests that being good at English is indeed part of a Swedish national identity. Frequent code-switches to English, particularly among the young, can also be linked to positive perceptions of English where the use of English can be a means of constructing an identity as a member of an urban, global community. Similar findings have also been reported for Denmark, with abundant use of English being a characteristic feature of youth language (Preisler, 2003).

A recent study on the use of and attitudes towards American and British English accents among Norwegian adolescent learners (Rindal, 2010) indicates a high level of English proficiency in that the students managed to exploit the two English varieties for their own purposes of self-presentation. It was found that most students preferred British English pronunciation for more formal and school-oriented interactions, whereas American English was favoured in informal contexts and peer-group interactions. Rindal (2010: 255) argues that ‘learners create social meaning through stylistic practice by choosing from the English linguistic resources available’ and that the findings ‘give strong indications that the learners make use of L2 in their construction of identity’.

Skills and attitudes among Scandinavians in general: The Eurobarometer

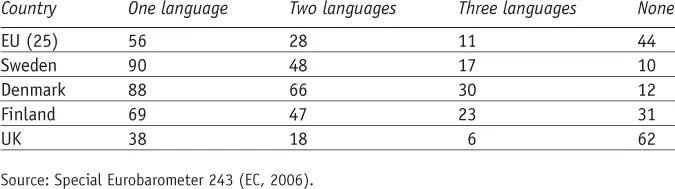

Results from the Eurobarometer survey of language skills of Europeans (EC, 2006) show that the overwhelming majority of Scandinavian respondents speak at least one other language in addition to their first language (see Table 1.2).

The results for the Scandinavian members of the EU are, as can be seen from Table 1.2, significantly above the EU average, based on the 25 member states at the time of polling (results for the UK, which displayed the lowest command of other languages, have also been included for comparison). As many as 90% of Swedish respondents report they know one foreign language well enough to have a conversation in that language.

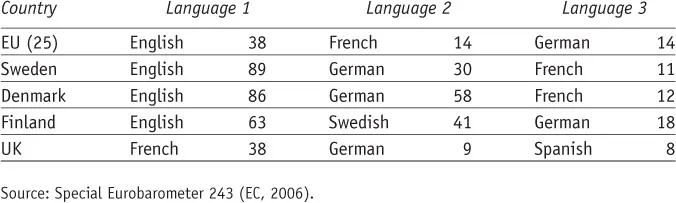

Setting aside first language speakers of English, the language that most respondents say they are able to have a conversation in is, not unexpectedly, English (see Table 1.3). It is also worth noting that the dominance of English is particularly pronounced in Sweden. There, the tendency to invest in one language is stronger than in the other Scandinavian countries, where many more also say they can have a conversation in at least two languages in addition to their first language (see Table 1.2).

Overall, respondents from all 25 EU countries are very positive towards knowledge of foreign languages. Most positive are the Swedes, where 99% agree with the statement ‘Do you think knowing other languages than your mother tongue is, or could be, very useful ... for you personally?’, with 97% of respondents saying English is the most useful language. These results are almost identical to the Swedish Grade 9 students’ positive evaluation of the usefulness of knowing English (98%).

So far the overview points to the widespread knowledge of English in Scandinavia where English language proficiency is regarded as something positive, in particular for international contacts and cross-cultural communication. Being good at English, as noted above, even seems to be a marker of national identity, at least for young Swedes (Oakes, 2001). These are factors that all promote the use and increased spread of English. As outlined in the next section, debate about the role of English in Scandinavian countries has mainly concerned the rapid spread of English in certain domains, where concerns have been raised that the high level of proficiency might prove to be a threat to the long-term survival of the national languages.

Table 1.2 Which languages do you speak well enough to be able to have a conversation excluding your mother tongue? (percentage of respondents)

Table 1.3 The most widely known languages (percentage of respondents)

English in the Domains of Higher Education and Research in Sweden

The following section examines the role of English in the domains of higher education and research, and explores the link between the actual linguistic situation and language policy and planning, using Sweden as an example.

Transnational student movements in an increasingly global education market have led to significant increases in the number of international students enrolled at Swedish universities. In 10 years the number of international students tripled to 36,600 (2008/2009 academic year), which means that one in four newly enrolled students was an international student. No doubt this development is linked to the high number of courses and programmes offered in English: 18% of all courses, 36% of all Masters-level courses, 25% of all programmes and 65% of all Masters-level programmes were offered in English (Cabau, 2011; Salö, 2010). In other words, the higher the level, the more likely that instruction takes place in English. In 2007 Sweden was in fourth position in Europe with regard to the number of programmes offered in English (123), after the Netherlands (774), Germany (415) and Finland (235) (Wächter & Maiworm, 2008). However, by 2008 the number of programmes offered in English in Sweden had increased exponentially to 530 (Cabau, 2011). These figures lend support to the argument that the globalisation of higher education has led to increased linguistic uniformity across Europe, as more and more countries offer courses taught in English to attract international students (Graddol, 2006: 77).

The large number of courses and programmes offered in English, however, does not necessarily mean that English is always used. On the one hand, Swedish is often used, to some extent, in subjects that are advertised in the university handbook as being offered in English. Söderlundh (2010) investigated the use of Swedish in university courses offered in English with a large proportion of international students. She studied language choice both in the classroom and in more socially oriented contexts during breaks. Her results show that Swedish-speaking students often use Swedish among themselves in group work and when addressing the teacher. Also, if no non-Swedish speakers are present in the classroom, interaction usually shifts to Swedish. On the other hand, subjects advertised as being offered in Swedish are not ‘islands of Swedish’, as the required reading is often partly in English.

As the language of research dissertations, English has increased its share significantly and is now completely dominant. For example, in 1920 about 15% of all doctoral theses were written in English, in 1960 its share had increased to 70%, and in 2008 87% were written in English. During the same period, the use of Swedish for doctoral theses steadily decreased from 50% in 1920 to 12% today. However, it is worth noting that the use of English is very unevenly distributed between disciplines, with 94% of theses in natu...