![]()

1 Teaching languages online: the essentials

- This initial chapter discusses the fundamental concepts involved in online language teaching and introduces the approach and format for the proceeding chapters.

- With the focus in this and subsequent chapters being on active teaching in online venues, foundations of task design and their orchestration via instructional conversations are established.

- The chapter supplies definitions for the four online language learning environments and their affordances.

- Fundamentals of designing task toolkits for online language teaching are outlined and illustrated.

What this book is about

Available time

Instructional time

Task design

Management

Content/Sequencing

Assessment

The four environments

Blended learning

Learning community

A sociocultural view of language teaching and learning

Why online?

Traditional forms of f2f classroom discourse

Instructional conversations

Conclusion

End-of-chapter activities

References

Teaching languages online: the essentials

There is no question that teaching and learning languages online is growing in popularity. The reasons for this growth are many. Chief among them is the matter of convenience. Rather than traveling distances short and long to participate in face-to-face (f2f) courses, people wishing to study a new language have only to turn to their computer or mobile screens at any hour of the day or night and access instruction. The forms that this instruction takes are many and varied; some depending on instructors, some depending on stand-alone instructional materials and many a combination of both. Moreover, many language educators who teach in the traditional f2f classroom are making good use of online tools and materials as complements to their courses as places where students can practice and study outside of class time. In short, the amount of instructional activity taking place in cyberspace is enormous and, as we hope you will find in this text, enormously exciting.

Those who are skeptical about online learning tend to point to the loss of the fast-paced, stimulating interaction that takes place in live language classrooms. It is true that the timing, and with it the dynamics of interactions is radically different. However, as we explore throughout this text, there are numerous affordances that can, when exploited by excellent instruction, mitigate the absence of live interaction. Indeed, since we first began teaching online several years ago, students report that where they once enjoyed the lively pacing and adrenaline of live classes, they were finding the timing aspect in online forums more to their liking. This seems especially true for learners who are less outgoing in live contexts; the luxury of time and quasi-anonymity work in their favor. Language learners who otherwise do not react well under the pressure of real-time comprehension and production in live classrooms particularly enjoy online language learning.

What this book is about

This text lays out methods and their rationale for optimal uses of online environments for effective language teaching. It primarily addresses professional language educators, those new to the field, those with experience in traditional classrooms and those who teach partly or fully online. Our three foundational premises are as follows.

- Language learning is made up of primarily social/instructional processes.

- Online environments can be used well socially and instructionally.

- Teaching well in online environments requires skilled instruction.

We therefore focus on the kinds of teacher instructional moves in conversation with students, what we call, along with Tharp and Gallimore (1991), ‘instructional conversations’ that in our work are proving highly effective for teaching language in online environments. Before expanding further on these three foundational premises for our approach to online language teaching, we will address some essential practical matters that concern the mechanics and logistics of online teaching: time, management, learning goals and assessment.

Available time

Online teaching and learning can take place as it does in f2f classroom synchronously, that is in real time, or asynchronously, whenever it is participants choose to interact. Both of these teaching modes require conceptualizations of time that are quite different from traditional meet-four-times-a-week planning and participation structures. At the beginning design stages, the development of online instructional elements is time consuming. In the long term, however, the fact of having all materials and structures in a single place is a time saver. In regard to the actual teaching/contact time with students, online teaching is often viewed as requiring more time than face-to-face as instead of having contact with students three to four times per week, one is having contact every day. And, as mentioned earlier, students who would otherwise shy away from actively participating in f2f contexts are more than likely contributing more and more often for reasons we will discuss shortly. This in turn compels instructors to be more actively and continuously responsive throughout the term. Although instructors are quick to point out these time investments, they are also quick to qualify these by citing other areas where enormous amounts of time are saved. We mentioned having all one’s course materials in once place. In addition, there is the matter of convenience. Many online instructors log onto their courses when it suits their schedules; not at 11:00 am every Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, but rather some days, evenings or mornings as their schedules permit. Traveling to and from a physical classroom, parking, meals away from home, even clothing and childcare can all be factored in to counterbalance the time investment in online education. Most instructors who calculate and consider the shifts in how their time is spent testify to the increase in the quality time they can spend teaching well in exchange for time spent on activity extraneous to actual instruction.

Students also enjoy the time savings of online learning. For many contemporary students, the time and logistics of traveling to a physical classroom according to a set schedule can be challenging. Students who work and who have families can study anytime and anywhere that suits their busy schedules. There are the larger life time issues and then there is the matter of instructional time itself.

Instructional time

In addition to available time (above), this text is particularly interested in instructional time; that is, the time that both instructors and learners have to carefully consider the form and content of their online postings in online venues. For learners, it is within this thinking, comprehending and composing time that active language learning is taking place. For instructors, it is within this thinking, comprehending and composing time that optimal instructional conversation moves can be devised given the current status of the class discussion. Both students and their teachers can, moreover, use this time to access any and all information they need to comprehend, compose and instruct. For students, the most obvious example might be taking advantage of online resources such as dictionaries, thesauruses and even native speaker friends in composing their posts. For instructors, they can access and in turn make use of background cultural information, artifacts, visuals, animated grammar explications and the like to amplify instructional conversation moves.

Task design

Like in the traditional f2f language classroom, a major part of instructional routines involves tasks in which learners engage with the aim of their practicing and thus learning target language forms and functions. A language learning task can be thought of as a structured activity that has clear instructional objectives, content and context that is culturally authentic and appropriate and specified procedures for its undertaking. Tasks are, then, activities in which learners engage for the purpose of mastering aspects of the target language under study. They range in complexity from brief language workouts (e.g. listen and repeat, listen or read and perform a grammatical transformation) to more complex activities such as role play simulations, group decision making, or sustained interactions with native speakers for problem solving. The essential element that defines language learning tasks is the purpose, objective or outcome of the task, an element that we will stress throughout this text. It is through a consistent focus on task objectives that teachers make productive use of instructional conversation moves to guide and enhance the learning.

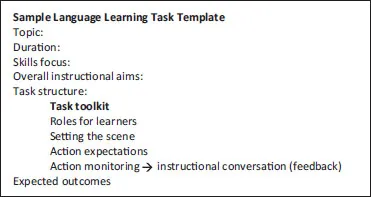

Figure 1 Sample language learning task template

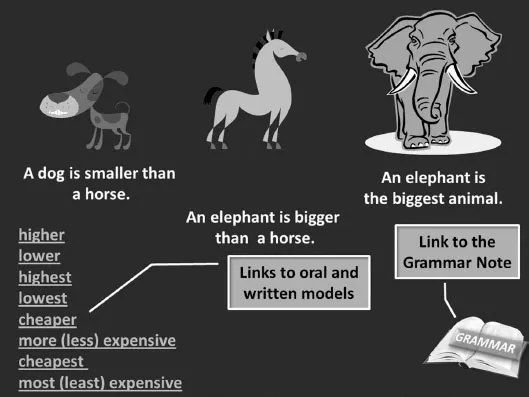

The task toolkit is a convention that we use throughout this text. It is the set of language elements that make up the focus of a given language task. One advantage of online instruction in this regard is that these toolkits can be collected and managed in a course task repository and reused as needed. The information in the task toolkit should be as simple and direct as possible as it is to these language elements that instructors and students refer as they undertake and evaluate the processes and outcomes of the given task. Our convention is to place this boxed text in the upper right-hand corner of all screens as a consistent anchoring and referencing tool (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2 Sample task toolkit

Roles for learners can be specified much as they are in the live classroom. In online environments, however, one can also provide links to background language and cultural information concerning the roles that learners are assigned. If, for example, a student is assigned the role of a bank manager in a bank robbery role play, links to target culture sites and information (video clips are particularly useful in understanding target culture social roles) can be included in the description of the particular assigned role. In this way also learners can have background about one another’s roles so as to better attune their communication patterns with one another.

Similarly, in setting the scene for a language learning task, students and instructors have at their fingertips massive amounts of background information in multimodal forms. Taking the bank robbery role play task as an example, learners can see and explore banks and banking routines, even delve into famous historical robberies in the target culture as part of preparing to undertake the task.

Action expectations and action monitoring constitute the heart of powerful instructional conversations. As you will see throughout the text, this aspect of language learning tasks is where we believe the real teaching and learning occur. Learners are expected to comprehend and produce specified language correctly (action expectations) and instructors monitor accordingly. In monitoring these task-guided conversations, instructors seek out teachable moments – moments where learners need a push, a reminder, reference to the task goals and/or task toolkit, or probes of their understanding of target culture and context. These teachable moments represent rich opportunities in online environments in terms of time and available resources as we discussed above. We will discuss the goals and anatomy of instructional conversations more thoroughly at the end of this chapter and, subsequently, illustrate these throughout the remaining chapters.

Management

Managing ten to thirty students three or four times per week in traditional classroom settings is onerous. How does one manage the learning in online environments? As mentioned earlier, the sheer fact of having all of one’s materials, all student work, all archives of what has taken place in one online location is a great time saver in the long term. Being able to revisit what has already occurred in class over time can be a powerful management tool in assisting with future instructional planning as well. Managing all of this information can be facilitated through the use of a Course Management System (CMS) whereby special tools are provided to track learners, their assignments, their participation structures and their contributions. Thus, the kinds of continually and automatically updated information about online learning activity can greatly ease the overall management of coursework that takes place online.

An element of management that can in large part determine the level of success for an online course or online component of a course is the setting of norms and expectations. Because learners are structuring their own time in these online venues, the amount and quality of their participation for optimal learning, and optimal grades, need to be clearly specified and pointed to throughout the term. Actual models and exemplars of optimal participation structures can be provided so that learners are 100% clear on the mode, purpose and level of quality expected. Reminders of these expectations can be visually present and pointed to throughout the term.

In addition to management, one of the most critical features of successful online instruction as reported in research studies is the online behaviors of the instructor. When students log on to their cours...