![]()

1 Understanding Demotivation

Definition of Demotivation

How can teachers help students to be more motivated to learn a foreign language? This is a question that many foreign language teachers ask themselves, and I have been looking for the answer to this question following the experiences that I described in the Introduction. Researchers in the field of motivation in second language learning have argued that motivation is a crucial factor in language learning and that there are a variety of measures that teachers can take to improve learner motivation.

Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of teachers, many learners lose interest in foreign language learning. As Dörnyei (2001: 141) points out:

Classroom practitioners can easily think of a variety of events that can have demotivating effects on the students, for example public humiliation, devastating test results, or conflicts with peers. If we think about it, ‘demotivation’ is not at all infrequent in language classes and the number of demotivated L2 learners is relatively high. (Dörnyei, 2001: 141)

Dörnyei’s concern is that no matter how hard teachers try to encourage their students, there will always be a certain number of demotivated learners. Demotivation seems to be particularly widespread in Japanese high school English classrooms and, as briefly described in Introduction, it can occur for a variety of reasons (see Kikuchi [2013] for a detailed review of this issue). Before defining demotivation, the central theme of this book, let me briefly provide a definition of ‘motivation’. Demotivation combines the prefix de- and the noun motivation. As an important first step, it is necessary to think about how we should view motivation. While motivation is the process that drives learners to move toward a goal, demotivation is the negative process that pulls learners back. An understanding of demotivation follows more easily from an understanding of motivation.

Working definition of motivation

It is useful to understand how lay people may conceptualize motivation. Table 1.1 describes definitions of motivation found in three different online dictionaries. As can be seen, the definitions vary greatly, ranging from inner feelings, such as desire, drive, interest or willingness, to the act itself, to a condition and to a process. By simply taking a look at the dictionary entries, you may understand the difficulties of defining motivation.

Table 1.1 Definition of motivation in online dictionaries

| Source | Definitions |

| Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary | Willingness to do something, or something that causes such willingness |

| Collins English Dictionary | (1) the act or an instance of motivating; (2) desire to do; interest or drive; (3) incentive or inducement; (4) (psychology) the process that arouses, sustains and regulates human and animal behavior. |

| Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary | (1) the act or process of giving someone a reason for doing something: the act or process of motivating someone; (2) the condition of being eager to act or work: the condition of being motivated; (3) a force or influence that causes someone to do something. |

Among these dictionary entries, Collins English Dictionary includes a definition related to psychology. This definition is closest to the working definition that is used in this section. Based on Schunk et al. (2008: 4), I would like to view motivation as ‘the process whereby goal-directed activity is instigated and sustained’. In their perception,

The term motivation is derived from the Latin verb movere (to move). The idea of movement is reflected in such common-sense ideas about motivation as something that gets us going, keeps us working, and helps us complete tasks. Yet there are many definitions of motivation and much disagreement over its precise nature. (Schunk et al., 2008: 4)

In preparing for this book and consulting many resources, this definition of motivation as a process that involves goals and requires activity to be activated and sustained made the most sense. In the field of language learning motivation, Dörnyei and Ushioda (2011: 4) state that motivation concerns (a) the choice of a particular action, (b) the persistence in that action and (c) the effort expended. In this vein, I view language learning motivation as a process in which learners choose to learn a language and put effort into doing so.

Researchers’ views of ‘demotivation’

How has demotivation been viewed in the literature? Zhang (2007: 213) defined it as ‘the force that decreases students’ energy to learn and/or the absence of the force that stimulates students to learn’. Zhang, who conducted a study about demotivation that utilized the framework of instructional communication studies developed by Christophel and Gorham (1995; Gorham & Christophel, 1992; Gorham & Millette, 1997), argued that various teacher-related factors (e.g. teachers’ incompetence, offensiveness and indolence) can become negative motivational influences.

Dörnyei (2001a: 143) defined demotivation as ‘specific external forces that reduce or diminish the motivational basis of a behavioral intention or an ongoing action’. He argued that demotivation is different from amotivation, which refers to a lack of motivation that is most closely associated with self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2002). Dörnyei considers demotivation to be related to specific external forces that cause a reduction in motivation. In Dörnyei’s (2001a) conceptualization, amotivation refers to a lack of motivation caused by the realization that there is no point in studying a foreign language, or a student’s belief that studying a foreign language is beyond his or her capacity. Based on Vallerand’s (1997) conceptualization of amotivation, people can be amotivated because of various beliefs (e.g. capacity–ability beliefs, strategy beliefs, capacity–effort beliefs and helplessness beliefs). Due to these beliefs, a relative absence of motivation can occur. As stated by Dörnyei (2001a: 143), ‘amotivation is related to general outcome expectations that are unrealistic for some reason, whereas demotivation is related to specific external causes’.

The problem with this definition of demotivation, however, is that it has not yet been empirically determined whether or not demotivating factors are completely external. A number of researchers (e.g. Arai, 2004; Falout & Maruyama, 2004; Tsuchiya, 2004a, 2004b, 2006a, 2006b) included in their studies of demotivation both external factors, such as teachers and class materials, and factors that are internal to the learner, such as a lack of self-confidence and negative attitudes. Despite his conceptualization of demotivation as being caused by external factors, even Dörnyei (2001a) listed two internal factors, reduced self-confidence and negative attitudes toward the foreign language, as sources of demotivation. Therefore, Kikuchi (2011) has added the notion of internal to Dörnyei’s (2001a) definition and defines demotivation as ‘the specific internal and external forces that reduce or diminish the motivational basis of a behavioral intention or an ongoing action’. Based on this definition, I refer to these individual internal and external forces as demotivators in this book.

Note that the studies included in the following chapters are not only about demotivated learners. The participants in most of the studies are a mix of motivated and demotivated learners. This is a very important conceptual issue that I will return to in Chapter 9.

It is also important to note that students’ motivation to study English fluctuates (Koizumi & Kai, 1992; Miura, 2010; Sawyer, 2006). Demotivation does not necessarily mean a lack of motivation; demotivation also occurs, for instance, when the motivation of a highly motivated student decreases to an average level. In terms of motivational fluctuations, the level of motivation might decrease from the beginning of the student’s English study over many years.

Working definition of demotivation

In the previous section, I clarified that what scholars have referred to as ‘demotivation’ will be treated as demotivators in this book. In this section, I will define the term demotivation for this book. I introduced the working definition of motivation in the previous section, Now, I will work with the prefix to motivation, de-.

According to the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, the prefix de- can mean (a) do or make the opposite of; reverse; (b) remove or remove from; (c) out of; (d) reduce; or (e) derived from. While language learning motivation concerns the process that involves goals and requires activities to arouse and sustain motivation, demotivation concerns the negative process that pulls learners down.

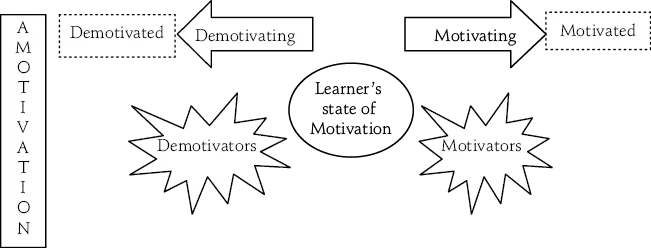

In terms of the perception of demotivation in the literature, scholars use the word demotivation in different ways. From my understanding, the term demotivation can be differentiated from demotivators, demotivating and demotivated. Figure 1.1 represents the conceptualization of these four words, along with the positive side of this concept, motivation, and a complete loss of motivation, amotivation. As I discussed above, first of all, I see demotivators as ‘the specific internal and external forces that reduce or diminish the motivational basis of a behavioral intention or an ongoing action’. The pull, or series of demotivators, that makes people ‘demotivated’ can be seen as demotivating. We can use this word demotivating as an adjective.

Figure 1.1 Concept of demotivation and demotivators

I would also like to discuss the difference between demotivation and amotivation. As I described, demotivation concerns the negative process that pulls learners down. I see, however, that demotivation is situational, and demotivated learners can still be motivated again. In contrast, amotivation concerns a lack of motivation. Vallerand and Ratelle (2002) describe amotivation as follows:

Amotivation is at work when individuals display a relative absence of motivation. In such instances, individuals do not perceive a contingency between their behaviors and outcomes, so they do not act with the intention to attain an outcome… They begin to feel helpless and may start to question the usefulness of engaging in the activity in the first place. (Vallerand & Ratelle, 2002: 43)

Language learners who have become amotivated pro...