![]()

1Introduction

Focus of the Book

Our contemporary reality is characterised by the unavoidable mingling of languages in the different spheres of everyday life. And this is why different bi- or multilingual practices, such as translanguaging, polylanguaging, cross-languaging, code-switching and code-mixing, have raised interest within the fast-growing field of multilingual studies. Within this environment, questions have emerged about when, why and how people make constructive use of the resources they have available to communicate and create socially purposeful meanings. It is because of the concern regarding the type of skills and strategies that one needs to participate effectively in today’s multilingual and superdiverse1 societies (cf. Hornberger, 2007; Hornberger & Link, 2012) that multilingual practices have also attracted the attention of scholars in the fields of foreign language learning, teaching and assessment. These scholars are increasingly interested in investigating multilingual competences and skills, in order to approach foreign language teaching and testing differently – i.e. in ways that will cater to the new and immediate communication needs of members of the new multilingual environments, which impose new realities, challenges and demands on language users.

Cross-language (or interlingual) mediation,2 with which this book is concerned, is one of these communicative practices directly linked to the emergence of multilingual and multicultural societies. Speakers around the globe are continuously called on to act as mediators, i.e. to use more than one language to bridge communication gaps between speakers of different languages who are unable to directly communicate with one another. In the field of foreign language teaching, learning and assessment, mediation became a legitimate object of concern through its inclusion in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Teaching, Learning, Assessment – henceforth CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001). This important document, whose basic purpose is ‘the provision of objective criteria for describing language proficiency … [in order to] facilitate the mutual recognition of qualifications gained in different learning contexts… and [hence] aid European mobility’ (Council of Europe, 2001: 1), offers detailed descriptors illustrating what language users can (or should be able to) do, in each of the six levels of language proficiency (A1–C2), with regard to reading and listening comprehension, and written and spoken production/interaction.

The problem is, however, that despite the fact that the CEFR has put mediation forward as an important aspect of language users’ proficiency, it provides no benchmarked illustrative descriptors (or can-do statements) (cf. Alderson, 2007; Little, 2007; North, 2007). This omission, due mainly to the lack of data about learner mediation performance, which would allow a description of mediatory communication at each level of proficiency, has been a significant incentive for the research presented in this book. Given that no illustrative descriptors for the mediatory use of language are available in the CEFR, this particular language activity has seldom been included in foreign language curricula or featured in classroom activities. In addition, there are very few studies on how people mediate effectively - i.e. what strategies they use and what they do or do not do when they act as intermediaries trying to get what has been said or written in one language across to another. This is exactly what this book examines: Placed within a wider context of ongoing research conducted in Europe for the purposes of setting standards for language learning and assessment (cf. Alderson et al., 2004; Green, 2010; Krumm, 2007; Trim, 2012) and focusing on interlingual mediation as translanguaging practice, this book attempts to show what interlingual mediation entails, what processes are involved and what challenges the mediator faces with the ultimate aim being to help policymakers, educators and testers develop frameworks for the development and/or assessment of mediation competence.

What is Interlingual Mediation and Who is an Interlingual Mediator?

In this book, interlingual mediation is seen as both (i) a form of translanguaging which involves the interplay between languages and (ii) a communicative undertaking which entails the purposeful selection of information by the mediator from a source text in one language and the relaying of this information into another language (target text), with the intention of bridging communication gaps between interlocutors (who do not share the same language). Interlingual mediation, in other words, involves the interpretation of meanings in a text articulated in one language and the making of new meanings, on the basis of the ‘old’, appropriate for the situational context but in another language, as Dendrinos (2014) would aptly put it. Certain meanings and information in the source text are not only transferred to the target text but they are also transformed in order to fit the new context of the target text. The process can actually be said to be ‘a matter of recontextualisation – a movement from one context to another’ (Fairclough, 2003: 51). Furthermore, as stated by Bernstein (1990), when parts of texts are relocated through recontextualisation, they are often subject to textual change, such as simplification, condensation, elaboration and refocusing, also cited in Linell (1998: 145). Recontextualisation is defined by Linell (1998: 145) as the dynamic transfer-and-transformation of something from one discourse/text-in-context to another. He moves on to argue that recontextualisation involves ‘the extrication of some part or aspect from a text or discourse or from a genre of texts or discourses and the fitting of this part or aspect into another context, i.e., another text or discourse’. This movement of meanings from one text to another, and the creation of new ones definitely entails certain decisions on the part of the mediator, which need to be compatible with the conventions of the target text. Furthermore, in order to achieve his/her communicative goal, he/she also needs to put mediation strategies into effect and mediate between two different linguistic codes as will be explained later.

It has, however, to be stressed that it is not the source text itself that is transformed in the new (situational) context – this actually occurs in cases of translation, which in this book is sharply distinguished from the practice of mediation. In contrast, in the process of interlingual mediation, only extracted and relayed source meanings are transformed in order to be compatible with the conventions of the new context of situation. Each time that parts of a text and source meanings are used in another text (and thus in a different context), the source content is recontextualised, and is thereby given new meaning in the new context, a procedure that sometimes goes unnoticed. An analogous example of this process can be found in the field of medicine, where a doctor selects only certain pertinent information contained in the results of a patient’s blood test and then transfers/transforms the information and adapts certain meanings to the new situational context by simplifying or else popularising his/her discourse in order to convey relevant meanings to a patient.

The mediator is viewed as a plurilingual social actor actively participating in the intercultural communicative event, drawing on source language content and shaping new meanings in the target language. As Dendrinos (2006) puts it, the role of the mediator is to interpret meaning and then to create it through writing (or speaking) for readers (or listeners) of a different linguistic or cultural background. His/her task is thus to act as a ‘go-between’, giving voice to those who have lost it (Zarate et al., 2004: 57) and establishing the interaction between languages and cultures. In trying to build a communicative bridge by means of information in the source and target texts – and thereby creating an interchange between languages and cultures – the interlingual mediator functions as a link, participating in two different cultures at the same time. In the absence of a mediator, individuals who do not share the same language may not be able to successfully achieve a specific communication goal.

Furthermore, given that I do not expect the mediator to be totally fluent in both languages involved, my view of mediation as a translanguaging activity reflects a radical departure from the model of the ideal speaker (i.e. a proficient speaker of the target language). In my view, the plurilingual repertoire of the successful mediator, though differently developed in each language, enables him/her to access both languages (i.e. he/she is able to understand the one and express himself/herself in the other) in order to maximise communicative potential. By ‘plurilingual repertoire’, I am referring to the different linguistic resources available in each language which are selectively used by mediators when transferring information from one language to another according to the different task purposes. Moreover, during the process of trying to operate within and across generic or discoursal boundaries, the mediator unavoidably produces texts that simultaneously combine elements from two texts and two languages (Stathopoulou, 2009).

What Does the Ability to Mediate Involve?

The ability to take part in an intercultural action, which involves relaying information from one language to another for a given purpose, seems to form part of the mediator’s interlingual competence and part of his/her ability to communicate in the target language.

During the act of mediation, the mediator’s linguistic and cultural knowledge along with his/her capacity for simultaneously drawing on different linguistic and cultural resources are activated and used.

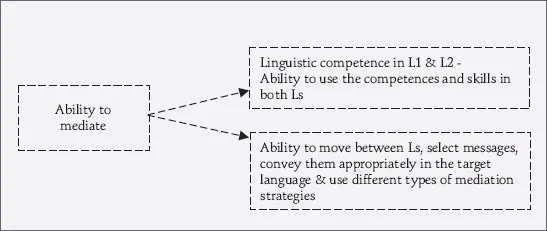

Specifically, as Figure 1.1 shows, language users’ ability to mediate and translanguage not only involves being competent in two languages and making use of their linguistic knowledge, or selecting from a repertoire of possible meanings which of them to convey, but it also entails being competent in moving between languages and in relaying information from one language to the other according to the rules and possibilities of the communicative encounter. Thus, mediation strategies come into play and ultimately determine the success or failure of the end product. In other words, for a mediator to complete his/her task successfully, he/she may combine information from different sources, i.e. either his/her background knowledge of a topic or the source text. He/she may also reorganise source text sentences or whole paragraphs and may summarise source information into its gist, either in a single sentence or in more than one sentence. Another very successful strategy is textual integration and reformulation of the exact words of the source text, especially if it is combined with synthesising, creative blending or summarising. Of course, the aforementioned strategies are not independent of the task at hand. Being able to mediate also implies dealing with task requirements in such a way that the outcome will include – apart from the appropriate language – those mediation strategies conducive to the task at hand, thereby contributing to the success of the mediation.

Figure 1.1 Schematic representation of the ability to mediate

In order to mediate effectively, the mediator must perform a series of preparatory actions, including that of purposefully selecting information, ideas and messages from the source text. In fact, depending on the task at hand, the mediator is required to select which messages to transfer into the target language in order to bridge the communication gap, and to decide the linguistic means through which to transfer them and the mediation strategies that will be used in the process. Evidently, therefore, ‘selection’ is at the core of mediation and is a key term in any attempt to define it. In this book, mediation is regarded as a process in which social actors, i.e. the mediators, select from a range of linguistic alternatives within a repertoire of forms determined by previous learning. This view can also be linked to the definitions of verbal communication suggested by Bernstein (1961)3 and Gumperz and Hymes (1972/1986: 432, found in Coste & Simon, 2009: 172), in which the importance of social constraints in determining the process of selection in verbal communication are highlighted. Although a matter of individual choice, this selection on the part of the social actor from among the diverse resources at his/her disposal is ultimately determined by the social context and the interpersonal relationships involved while mediating. Note that the link between the ‘individual’ and the ‘social’ has also been raised by Moore and Castellotti (2008) and Coste and Simon (2009), attempting to define plurilingual competence.

An important issue related to the ability to mediate that needs to be raised at this point is linked to the status of the two languages involved in the mediation process. Borrowing Trim’s (2004, in Pachler, 2007: 7) words, while mediating, the two ‘languages are not seen as simply existing side by side, quite separate in the mind, but as interacting to form one integrated competence upon any part of which a user may draw to meet the demands of communication’. In other words, the two languages and cultures, which are negotiated for communication, are not kept by the mediator in separate mental compartments, but rather they are used simultaneously, since they are in a constant dialogic relationship. Mediation ability, which forms part of both the multilingual/plurilingual competence – as defined by Coste and Simon (2009: 174) – and translanguaging competence, is ‘not conceived as the sum of competencies in distinct languages but as one global but complex capacity’ which may be more or less developed, depending on the mediator’s proficiency in each of the two languages or his/her linguistic experiences. Coste and Simon (2009: 174) stress the importance of the development of plurilingual competence as, according to them, it actively contributes to the construction of democratic citizenship and the struggle against exclusion. As a matter of fact, this non-separatist approach to viewing languages that come into creative contact is also reflected in the Inventory of Mediation Strategies (IMS) proposed herein, as the strategies detected and included in the model reflect the existence of a source text from which target content is drawn.

Another important factor involved in the ability to mediate – and one which determines the product of mediation – is the context in which mediation occurs, namely: who mediates, for what purpose, in which discourse environment, what type of text he/she produces and from what type of text he/she relays information. Contextual features have to be taken into account by the mediator if he/she wishes to be successful in his/her task. As becomes evident, mediating is in itself a complex undertaking, and one which is rendered even more complex when the genre of the original text does not coincide with that of the target text because the mediator needs to coordinate the generic conventions of two different texts. In this case, however, the mixing of conventions seems to be unavoidable, thus rendering the target text hybrid (Stathopoulou, 2009).

The Research

This book presents research which had been designed to gain a multileveled understanding of the mechanisms of interlinguistic mediation4 in a testing context. The study was concerned specifically with interlinguistic mediation involving Greek learners/users of English, and it focused on wr...