![]()

1Child Language Disorders Across Languages, Cultural Contexts and Syndromes

Janet L. Patterson

This book is about children with language disorders who speak languages other than or in addition to English. The authors address a wide range of clinical and theoretical questions. For example, what do we know about the course of development in bilingual children with Down syndrome (DS)? What language measures are available for French-speaking children? For Turkish-speaking children? How can we deliver early intervention services effectively to a Gujarati-speaking family living in London? Is the profile of strengths and weaknesses in Williams syndrome (WS) similar across languages?

The rich and increasing body of cross-linguistic research on specific language impairment (SLI) illustrates the value of a multilinguistic perspective for theory testing and development, as well as for clinical applications (e.g. Leonard, 2009, 2014; Paradis, 2010). This book extends a multilinguistic perspective to a wider range of child language disorders. This volume is organized in two sections. The chapters in the first section of the book focus on language disorders associated with four different syndromes in multilingual populations and contexts. The chapters in the second section of the book are language-specific, although the issues they address are relevant across languages and cultural contexts.

In the section on language impairments associated with specific syndromes, the first two chapters provide research reviews and clinical implications for bilingual children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD; Marinova-Todd and Mirenda, Chapter 2) and DS (Kay-Raining Bird, Chapter 3). These two chapters address important clinical and theoretical questions such as ‘Is learning two languages harder than learning one language for children with language disorders?’, ‘What language(s) should be included in intervention?’ and ‘Is the profile of typical strengths and weaknesses and the rate of language development different for bilingual children versus monolingual children with syndromes such as ASD or DS?’. In Chapter 4, Thorne and Coggins provide information on language and communication impairments among children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), assessment tools and intervention. Stojanovik reviews the literature on language and communication difficulties in Williams syndrome (WS) among English-speaking children and children who speak other languages (Chapter 5). The chapters on FASD and WS include discussions of assessment and intervention implications for children with these syndromes, regardless of the language(s) they speak.

The language-specific section of the book starts with To’s chapter (Chapter 6) on language impairment in Cantonese Chinese-speaking children. Her chapter includes information on Cantonese oral and written language; manifestations of language impairment in Chinese children with SLI, dyslexia and ASD; and clinical resources and guidelines for assessment and intervention. Although the clinical tools and strategies that To discusses specifically address Cantonese-speaking children, she and the authors of the other chapters in this section discuss assessment and intervention issues and strategies that are relevant to children with language disorders more generally. Stokes and Madhani (Chapter 7) present a framework for providing early intervention services and they demonstrate its application to working in London with children and families who speak North Indian languages (Panjabi, Gujarati and Bengali). Their chapter includes information on cultural and linguistic considerations for families from northern India, widely applicable clinical strategies for working with families in multilingual contexts and a case example to demonstrate the strategies. In Chapter 8, Elin Thordardottir provides a wealth of information on language development, primary language impairment (PLI) and assessment tools for French-speaking preschool and early school-age children, and she discusses important issues in developing and using valid assessment tools for monolingual versus bilingual children. Topbaş and Maviş (Chapter 9) focus on the development of Turkish language assessment tools and, more generally, the importance of developing valid language measures for identifying children with PLI or SLI. Without such tools, Topbaş and Maviş point out that children with SLI may not be provided with appropriate services since their needs will not be identified on the basis of associated cognitive, motoric or sensory impairments. In Chapter 10, Rodríguez focuses on dialectal differences in Spanish and the importance of taking linguistic variation into account in language assessment.

Multiple Dimensions of Diversity

An understanding of the ways in which language disorders are manifested across languages enhances our understanding of the nature of language disorders and how to better serve children and families from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds. This book includes cross-linguistic information on patterns of language growth and weaknesses among children with SLI, and among children with language impairments associated with other developmental difficulties and diagnoses. Thus, the diversity in this book extends to variation within and across clinical populations as well as across languages and cultures.

Although there are many language-specific and culture-specific facts, details, assessment tools and intervention recommendations included in this volume, this book is intended to provide a foundation for working with multilingual children and families in general, including those who speak languages not specifically addressed in this book. Examining language disorders in widely divergent circumstances (different languages, monolingual versus bilingual, different cultural contexts and different diagnoses and developmental disabilities) gives us a perspective on the range of considerations necessary for clinical practice when we work with children who speak languages other than those specifically addressed in this book. An understanding of diversity among children with language disorders is a key not only to understanding what is language-specific and culture-specific, but also to identifying commonalities across languages and across cultural and clinical contexts.

Diversity in languages

An encyclopedic knowledge of all of the world languages isn’t necessary or feasible for clinicians and researchers. However, an understanding that what is true of one’s native language(s) is not necessarily true of other languages and a familiarity with some of the ways in which languages vary provide a foundation for good clinical practice and research. Cross-linguistic research allows us to examine how language works in general, without depending on assumptions based on our understanding of a particular language. As Slobin (1985) pointed out in a classic series on language acquisition in 15 languages, cross-linguistic research is essential for identifying universal aspects and principles of language acquisition. Subsequently, there was a growing recognition of the importance of cross-linguistic research for clinical work and for identifying and testing theories about underlying mechanisms involved in language breakdown in aphasia (e.g. Bates et al., 1991) and on the nature of SLI (e.g. Leonard, 1990, 2009, 2014). Cross-linguistic research on child language disorders associated with other diagnoses such as WS, DS, FASD and ASD can further our understanding of commonalities and differences in language development in diverse circumstances and populations.

The languages represented in this book vary widely in their structural characteristics. Three points of divergence are noted in particular here: word order, morphological typology and writing systems.

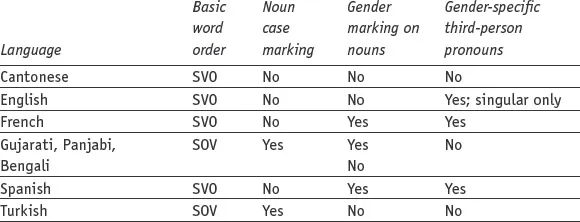

The most common word order across languages is subject-object-verb (SOV) and the second most common is subject-verb-object (SVO), the basic word order of English. As shown in Table 1.1, SOV is the basic word order of Turkish and of the North Indian languages, Panjabi, Gujarati and Bengali, languages discussed in two chapters in this book. Three chapters focus on languages in which SVO is the basic word order (Cantonese, French and Spanish). The flexibility of word order and the degree to which the subject must be stated also vary across languages. In some languages, grammatical relations – the ‘who does what to whom’ information – are indicated by verbal affixes rather than solely by word order. In those languages, the subject may be omitted and word order may vary for pragmatic purposes, such as for focus or emphasis. In contrast, in languages such as English in which grammatical relations are indicated largely through word order, there is less variation from SVO word order and subjects are almost always stated in declarative statements.

Morphological typology, the classification of languages according to the way morphemes are put together to form words, is quite varied in the languages considered in this volume. Linguists generally classify languages as being either analytic (isolating) or synthetic. Analytic languages, like Mandarin and Cantonese, construct sentences through the use of isolated morphemes, without the use of affixes. Synthetic languages, in contrast, express meanings by combining free and bound morphemes. Synthetic languages may be agglutinating, like Turkish, where the affixes can easily be separated from the stems to which they are attached, and each affix generally conveys only one meaning. For example, ellerimde (in my hands) includes four morphemes: el (hand) + ler (plural) + im (my) + de (in). Another kind of synthetic language is fusional, where affixes and the bases to which they are attached are fused together in pronunciation and therefore are not easily separated from one another. In addition, there is generally a fusion of meanings that are represented by the affixes in such languages. As an example, verb forms in Spanish are marked for a range of inflectional categories, including person, number, tense and aspect in a single affix. For the verb, hablar (to speak/talk), hablo (I speak) and hablaron (they spoke), the -o in hablo conveys first-person singular, present tense, and -aron indicates third-person plural, past perfective.

Table 1.1 Selected grammatical characteristics of English and other languages in this book

The meanings expressed by affixes also differ across languages. In contrast with English, which has a sparse inflectional morphology, French and Spanish are moderately inflected, with specific inflections for verb tense, aspect and person, as well as number and gender marking and agreement in noun phrases (see Table 1.1). However, in contrast with Spanish, spoken French has many homophones for forms that differ in written language. For example, Elin Thordardottir (Chapter 8) points out that the spoken verb forms in j’aime (I love), tu aimes (you love), il aime (he loves) and ils/ells aiment (they love) are all homophones, although they differ in written form.

Turkish and the North Indian languages, Bengali, Gujarati and Panjabi, have multiple suffixes that are added to root nouns and verbs. Nouns are marked for case; for example, a suffix indicates whether a noun is a direct object (accusative case) or an indirect object (dative case). However, the specific types of suffixes vary across these languages. For example, Turkish does not mark gender with different forms for nouns, but two of the North Indian languages do.

As a final example of cross-linguistic variation in grammatical morphology, gender marking differs across languages for pronouns as well as nouns (and for other forms, as well). As shown in Table 1.1, English differentiates gender only in third-person singular pronouns (he, she, it), French and Spanish mark gender in third-person singular and plural pronouns, while Cantonese, Turkish and the North Indian languages do not differentiate gender in third-person pronouns (i.e. a single pronoun is used where English would differentiate he, she and it).

In addition to crosslinguistic differences, another important consideration is variation across dialects or varieties of languages. Rodríguez (Chapter 10) provides examples of phonological, morphological and syntactic variation in two varieties of Spanish that are widely spoken in the United States.

Diversity in written language systems is also found among the languages discussed in this book. In contrast with the alphabetic writing systems of English, French, Spanish, North Indian languages and Turkish, the written language used by Cantonese speakers is a logographic system, Modern Standard Chinese. To’s chapter on Cantonese illustrates variation in writing systems that can occur even within a language or language group. Because Modern Standard Chinese corresponds more closely to the spoken form of Mandarin than to Cantonese, Cantonese-speaking children experience a great difference between written and oral language when learning to read than Mandarin-speaking children do. Another difference in Mandarin- and Cantonese-speaking children’s experience is the use of an alphabetic system, Pinyin, which is taught to beginning readers in mainland China, but not in Hong Kong.

Among the languages with alphabetic writing systems, there is diversity in the scripts used. Latin scripts are used for English, French, Spanish and modern Turkish, but the degree of phonetic transparency or correspondence between spoken and written forms varies; for example, Spanish written forms correspond more closely to the pronunciation of spoken forms than English and French. Devanagari scripts are used for many languages, including Bengali, Gujarati and Panjabi. Although they vary in some details, Devanagari scripts are written from left to right and most consonants have an ‘inherent’ following vowel, ‘ɑ’ (Bright, 1996; Cardona, 1987; Klaiman, 1987). Other post-consonantal vowels are indicated with diacritic symbols added to the consonant, and vowels also can be indicated with independent symbols as needed, such as in word-initial contexts.

The details and range of variation across languages can seem overwhelming, even based on the small sample of cross-linguistic differences described here. Stokes and Madhani discuss the challenges clinicians face in working with multilingual populations and they provide a framework for working with children and families in early intervention when the clinician is not familiar with the languages...