![]()

Part 1

Conservation

Zoos are often presented as being like Noah’s Ark, a place of last refuge for endangered animals, maintaining a breeding population that can be used for future restocking of the wild. It is a widely used metaphor, popularised by writers such as Gerald Durrell and embraced by many. It is also a view that has been increasingly questioned and debated.

While zoos are highly popular tourist attractions, it is often argued that this role of providing pleasure to visitors is not enough in itself to justify removing animals from the wild and placing them in artificial enclosures. The entertainment role would only be justified, it is argued, if it was secondary to a conservation role. However, it is also often argued that zoos generally have not devoted enough of their resources to this role and changes in public attitudes to animals and their confinement have led to a shrinking market and support for zoos (for examples of these arguments see Bostock, 1993; Hancocks, 2001; Jamieson, 1985; Mazur, 2001; Shackley, 1996).

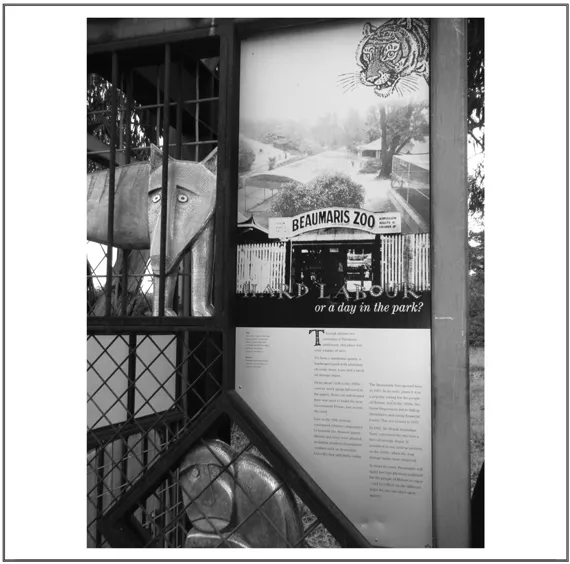

Historically, zoos have performed relatively poorly in conserving species. Two unfortunate examples serve to illustrate this. The first is the Tasmanian Tiger or thylacine. In 1936, the last known thylacine died at Beaumaris Zoo, Hobart, on a severe winter’s night after its keeper forgot to return it to its quarters (Figure T1.1). From the 1850s onwards, thylacines had been displayed in zoos in London, Washington, Vienna, Paris and Antwerp, as well as throughout Australia. They were popular due to their rarity, but no zoo engaged in a captive breeding programme or habitat conservation. Nor did they lobby the Tasmanian Government to remove their bounty (Paddle, 2000). It was only after the last in captivity had died that there were unsuccessful attempts to stock a breeding colony (Fleay-Thomson, 2007). The second example is a 1949 collecting expedition to the Cameroons in Africa by Durrell. His aim was to capture the rare Pygmy Flying Squirrel (Idiurus). Indeed, he collected over 30, but all died before he reached Britain (Botting, 1999).

Countering these failures are the successes of zoos in saving species, including the Mongolian Wild Horse, Père David’s Deer, European Bison, Oryx and Golden Lion Tamarin. However, it is argued that the number is quite small and it has been more a case of good luck that these have been saved (Hancocks, 2001; Shackley, 1996). Indeed, it might seem that some zoos engage in a form of greenwashing, trumpeting their role in saving animals, when they are really doing very little. Hancocks (2001) provides an example of a North American zoo that opened a ‘Chimpanzee Conservation Center’ with great fanfare, but which turned out to be no more than a new exhibit.

Perhaps the Ark metaphor is the wrong one and the debate needs to be shifted. In recent years, many zoos have demonstrated a much greater commitment to conservation through a wide range of programmes. There has been a realisation that just preserving a breeding population is not enough by itself. These newer conservation strategies comprise three components. The first is global collaborations, involving zoos, conservation bodies and protected area agencies. The second is working on conservation projects in the countries where the animals hail from, protecting habitat and preserving remaining populations. In this case, zoos become the public showcase for such programmes. The third (and newest) is zoos utilising their engagement with visitors to deliver persuasive messages as to how people can help conserve animals under threat. A good example of this is the current campaign for changes to food labelling laws so that consumers can see whether or not they include palm oil (the product responsible for rainforest clearing in southeast Asia). Zoos failed to save the Tasmanian Tiger, but by acting with collaborative partners, they may be part of the answer to saving the Tasmanian Devil and many other threatened species.

It is often argued that zoos are primarily for people (Mullan & Marvin, 1987; Rothfels, 2002). A large number of studies have consistently identified that people value zoos for the recreational experience more than conservation (see, e.g. Hancocks, 2001; Jiang et al., 2008; Mullan & Marvin, 1987; Ryan & Saward, 2004; Shackley, 1996; Tribe, 2004; Turley, 1999). The consistency of these results may seem worrying, though we need to realise that those surveyed were not asked to choose between recreation and conservation. It could be that both are important. As zoos change how they approach conservation, the challenge may be in convincing visitors that what they do has relevance to both the animals and the paying customer.

There are five chapters under this general theme of conservation. The first, by Catibog-Sinha, examines collaborative programmes between various zoos and the Philippine government. Four endangered species are covered by these programmes: the Philippine Crocodile, the Philippine Spotted Deer, the Philippine Cockatoo and the Visayan Warty Hog. Rather than just protecting these species in an ark, these programmes aim to reintroduce them to parts of the Philippines in cooperation with local agencies and communities. Intriguingly in these partnerships between Western zoos and the government of a developing nation, it is the Philippines who retains ownership of the animals and a dominant role.

In the second chapter, Shani and Pizam propose a new typology for zoos and other captive wildlife settings. Past typologies have tended to focus on the level of freedom the animals enjoyed, but this, it is argued, is too simplistic and fails to examine the underlying motives and values of the organisations operating these settings. Instead, Shani and Pizam argue for a typology based on Kellert’s nine basic wildlife values. Although these values represent general attitudes towards animals and nature, it is argued that they also best explain the various ways in which animals are displayed and exhibited in animal-based attractions.

The third and fourth chapters take a critical view of the conservation justification for zoos. Wearing and Jobberns argue that zoos, like much in ecotourism and nature-based tourism, do not stand up to scrutiny. While, they argue, there is often a rhetoric of conservation and nature-centeredness, the reality is that they are often primarily for the entertainment of tourists and achieve little for conservation. They present animal rescue and reintroduction centres as much more ethical attractions worthy of more promotion within tourism. Smith, Weiler and Ham argue the need for much more visitor research, particularly into motivations and how zoos can effectively communicate conservation messages to tourists.

The fifth chapter is an empirical study by Linke and Winter. Their interest was in applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour to zoos, searching for connections between attitudes and behaviour. Their study indicates that while visitors hold attitudes that zoos are equally important for their conservation, education and entertainment roles, the main reason for visiting tended to be to have an entertainment experience.

Chapter 2

Zoo Tourism and the Conservation of Threatened Species: A Collaborative Programme in the Philippines

CORAZON CATIBOG-SINHA

Introduction

Zoos worldwide are urged to address species conservation not only through long-term commitment to captive management and propagation, but also through environmental education, research, habitat conservation and reintroduction (WAZA, 2005; Zimmermann et al., 2007). This chapter discusses the collaborative agreement between the Philippines and several leading zoos overseas on the conservation of certain zoo animals. It examines the salient features of these institutional agreements in the context of wildlife conservation and the sustainability of zoo tourism. Based on the results of interviews with key staff involved in these programmes as well as an in-depth analysis of government documents (i.e. memoranda of agreement, legislations, treaties, biodiversity country reports and zoo accomplishment reports), this chapter explores the role of collaborative partnerships in sustaining zoo tourism and species conservation. The discussion is placed in the broader context of sustainability, which is grounded in the basic principles of biodiversity conservation, precautionary principle, public education and awareness, and community involvement/participation.

Zoos and Zoo Tourism

Zoo tourism involves direct interaction of visitors with wildlife under captive or semi-captive conditions. Zoos include zoological gardens, biological parks, safari parks, public aquariums, bird parks, reptile parks and insectariums; there are approximately 10,000–12,000 zoos worldwide (WAZA, 2005). However, more than 90% of zoos have substandard management in the care of captive animals and a poor record of involvement in the conservation of wildlife (Armstrong et al., 1993; Kelly, 1997; Van Linge, 1992). Nevertheless, there are some 1000 publicly or privately owned zoos worldwide, which are internationally recognised for their good practice in animal care and species conservation; they receive more than 600 million visitors annually (WAZA, 2005).

Zoos provide opportunities for visitors to view and interact directly with wildlife, despite the artificial or unnatural setting. According to Beardsworth and Bryman (2001), the zoo is very much part of the ‘tourist trail’. A survey of international tourists in Cairns, Australia, revealed that a majority of the respondents preferred direct wildlife encounters in controlled setting, either in a zoo or a wildlife park (Coghlan & Prideaux, 2008). Zoo tourism usually involves a one-day visit; it is generally a family-orientated leisure activity (Ryan & Saward, 2004; Turley, 2001). For some tourists, zoos cannot be ‘an effective substitute for viewing wildlife in their natural settings’ (Ryan & Saward, 2004: 260). On the other hand, others greatly enjoy the zoo experience that encourages them to travel and see wild animals in their natural habitats.

Zoos can serve as an excellent tool for promoting and imparting conservation awareness and learning. Zoos can take direct action to conserve species through education and conservation programmes, and these programmes can be integrated into zoo tourism (Catibog-Sinha, 2008a). The visitors surveyed in three Malaysian zoos, perceived zoos as a place for conservation, education, research and recreation. Those surveyed in Hamilton Zoo (New Zealand) placed a high value on viewing the animals (Ryan & Saward, 2004). Hunter-Jones and Hayward (1998) found that visitors, mostly children, surveyed from 200 zoos in the UK, placed great importance on watching and learning about the exhibits. The study by Woods (2002) revealed that the best tourist experiences in zoos were associated with wildlife interaction as well as an opportunity not only to view a large number and a wide variety of animals, but also to learn about them. The motivating factors for visitors surveyed in the Cleveland Metropark Zoo (USA) included not only enjoyment, relaxation and family togetherness, but also education. A survey of visitors at three Indian zoos revealed that zoos can help protect wild animals, such as the Lion-tailed macaques, and provide excellent learning venues to convey messages about conservation (Mallapur et al., 2008). A survey of visitors to Denver Zoo revealed that zoos are important for education (55%) and for conserving wildlife (29%) (Reading & Miller, 2007). Catibog-Sinha (2008b) reports that in the Philippines, visitors to a mini zoo within an urban park in Metro Manila benefited from their interaction with wildlife, discovering information previously unknown to them. Clearly, a well-planned interpretation programme will greatly enrich the recreational experience of zoo visitors and increase their appreciation of wildlife (Balmford et al., 2007; Rhoads & Goldworthy, 1979).

To promote the roles of zoos in conservation, research and education, several zoo operators/authorities formed a global zoo network, known as the World Association of Zoos and Aquaria (WAZA), subsequently formulating the World Zoo and Aquariums Conservation Strategy (WZACS). The strategy is a response to the challenges put forward during the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development and UN Millennium Development Goals. The strategy reaffirms that zoos are not merely for entertainment. It emphasises that zoos should have a prominent role in the conservation of wildlife, particular those with small populations, both in captivity and in the wild. Zoos are also expected to undertake a wide range of basic research in animal welfare and wildlife management. The role of tourism research in zoo management was highlighted by Frost and Roehl (2008). The research data are used to enrich the interpretative and entertaining aspects of zoo tourism, as well as provide the bases for improving the zoos’ educational and conservation management programmes (Mason, 2000; Mazur, 2001; Melfi, 2005; WAZA, 2005).

Zoo Animals: Threatened Species

Collectively, zoos maintain about 1 million living wild animals from various parts of the world. Half of these collections are mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians (WCMC, 1992), the majority of which are large in body size, colourful and have interesting behavioural characteristics (Churchman & Bossler, 1990; Puan & Zakaria, 2007; Turley, 2001; Ward et al., 1998). Unfortunately, many of these charismatic zoo animals are rare because they inhabit only certain geographical areas or they have restricted biological requirements or their populations have declined over the years due to habitat loss, over-exploitation or combinations of all these factors (Gaston & Blackburn, 1995; Miller & Lacy, 2003). Large animals, for example, are likely to become rare because they occur in low density and are often targeted by hunters for game and meat (Dobson & Yu, 1993). Because of their vulnerability and irreplaceability, many zoo visitors tend to sympathise with their situation. Hence, threatened species in zoo collections are used as flagships in fund raising and conservation campaigns.

To sustain zoo tourism, zoos need to acquire and maintain healthy animal collections. Zoos usually replenish their collections with animals trapped from the wild or those bred in captivity (Hanson, 2002; Holst & Dickie, 2007). However, acquiring threatened endemic species from the wild, especially from developing but biodiversity-rich countries, can be complex and even political. The global degradation and loss of natural habitats and over-exploitation of wildlife, coupled with tight government policies, have caused some difficulties in the acquisition and transport of zoo animals from the wild. Kelly (1997: 1) predicted that in the 21st century, the whole biota, ‘may need to be assembled from remnant and/or reintroduced endemic species in habitats that have been preserved or reconstructed’. Nonetheless, even these habitats are being rapidly transformed to other land uses, leading either to the displacement or the disappearance of many native wildlife (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005).

Zoos may also replace or replenish their collections from in-house captive breeding programmes or purchase captive-born specimens from other zoos. However, merely propagating zoo animals as replenishments is both inadequate and unsustainable. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that reproduction will be successful under captive condition because not all founders breed successfully, and if they do, some breed less than others. Moreover, proper genetic management and behavioural studies are crucial in sustainable zoo management. However, not all zoos have the technical and financial capabilities to undertake these measures. For instance, genetic uniformity in captive animals resulting from inbreeding must be prevented by increasing the founder population (preferably collected from the wild) or by moving animals (or their genetic materials, gametes or embryos) to various breeding facilities within a country or around the world (Catibog-Sinha, 2008a; Ellis & Seal, 1996). As part of good practice in zoo management, the movement of animals, including their genetic resources, should be monitored to ensure that the genealogical records of these animals are properly maintained. The creation of hybrids, which often have morphological and health problems, is bad public relations that responsible zoos do not wish to support.

Conservation Measures: In situ and Ex situ

Many modern zoos undertake sustainable zoo tourism through integrated management appr...