![]()

Part 1

City Tourism

Chapter 1

Organising City Tourism

Introduction

It is a truism that tourism is a complex activity. At one and the same time, it may refer to a systemtransport, an interaction of visitors and residents, a collection of trades and industries and to impacts of a commercial, economic, social and environmental kind. Unsurprisingly, therefore, ‘tourism represents a serious challenge to man’s ability to organise himself’ (Young, 1973: 180). Further exploration of the organisational aspects of tourism are found in several sources (e.g. Elliott, 1997) and in a practical vein, they are neatly summarised in a remark made over 40 years ago by the then executive head of the British Travel Association (a forerunner of today’s Visit Britain), whose name was Len Lickorish: ‘there are, if anything, far too many cooks involved in tourism and I would like to say that there always will be and so our biggest problem is how to resolve the old difficulty that when you have too many interests and too many helpers, each one of whom can contribute a little, how do you get them all to work together’ (cited in Heeley, 1975: 265). This chapter examines how in a city context tourism is typically organised so as to accommodate the multifaceted nature of the tourist industry with its private and public components and to deal with the attendant coordination issues. It begins by adumbrating a typology of city tourism organisation, before tracing its historical evolution. The final part of this chapter outlines the scope and content of the remainder of the book, providing inter alia a rationale for the case materials being utilised.

A Typology of City Tourist Organisations (CTOs) and City Marketing Organisations (CMOs)

This section presents an initial classification and clarification of the different ways in which cities have sought in organisational terms to exploit the opportunities occasioned by tourism and to brand and otherwise ‘position’ themselves with respect to their image and reputation. In the absence of centralised national approaches, the scope and content of city tourism organisation has been shaped essentially by local needs and circumstances, but with much copying of precedent and best practice. Two main structural approaches have arisen; one is set within the city government and involves the establishment of a team of tourism officers grouped into a department (or section of a department) and reporting directly to local politicians; the second is the public–private partnership in which a more or less independent tourism agency is formed out of a coalition of stakeholders drawn from the local public and private sectors. Looking at individual nations and across Europe as a whole, the resultant mosaic or ‘patchwork quilt’ of the city government and public–private partnership-based initiatives appears at first sight to be confusing, almost to the point of being anarchic. As well as the local government versus public–private partnership dichotomy referred to above, from one city tourist organisation (CTO)/city marketing organisation (CMO) to the next there are considerable variations with respect to nomenclature, budget, extent of geographical coverage and operational responsibilities. Some CTOs/CMOs are narrowly focused with a limited range of accountabilities, while others are expansive, multifunctional marketing and communication exercises.

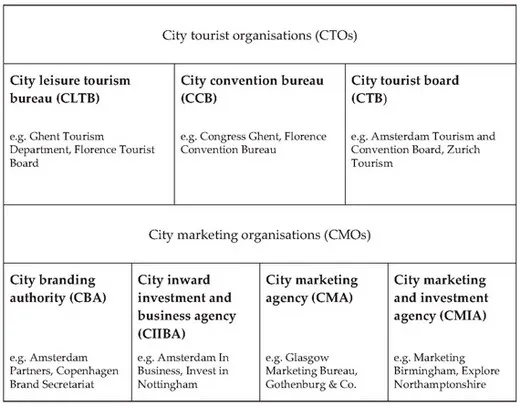

Figure 1.1 seeks to make sense of the heterogeneous nature of city tourism organisation, presenting a typology of CTOs and CMOs. City tourist organisations differ according to the degree to which they are responsible for attracting and servicing both leisure and business forms of tourism. City leisure tourism bureaux (CLTBs) are concerned only with leisure tourism, notably in the form of short-break holidaymakers and event-based tourists, while city convention bureaux (CCBs) address the so-called MICE sector – namely meetings, incentives, conventions and exhibitions. So for the Belgian city of Ghent, for instance, the Ghent Tourism Department (part of the city council) is the CLTB, while Congress Ghent (a public– private partnership) is the CCB. In many cities, however, leisure and business tourism functions are combined in the same organisation. This is the case, for instance, with the Munich Tourist Office and Visit Malmo (both part of the city government) and Zurich Tourism and the Amsterdam Tourism and Convention Board (ATCB) (both public–private partnerships). In Figure 1.1, I refer to these CTOs as city tourist boards (CTBs).

City marketing organisations (CMOs) are distinguishable from CTOs in that they are charged either with promoting city image generally (primarily through the vehicle of an overarching city brand) and/or with inward investment and business development functions. For instance, we shall see in Chapter 8 that Amsterdam Partners acts as the city branding authority (CBA), while Amsterdam in Business is the city inward investment and business agency (CIIBA). Both organisations exist independently of the CTB – the ATCB. A trend discernible in recent years is to combine tourism and city marketing functions into one organisation, and I refer in the typology to this type of body as a CMA – a city marketing agency. Brussels International and the Glasgow Marketing Bureau are examples. In the Scottish capital, Marketing Edinburgh will be established as a CMA next year, consolidating in one organisation the responsibilities of business and leisure tourism, film location marketing and city branding currently discharged by three separate organisations, namely the Destination Edinburgh Marketing Alliance, the Edinburgh Convention Bureau and the Edinburgh Film Focus. Finally, there are examples of a fourth kind of CMO – the city marketing and investment agency (CMIA) – in which tourism, city image/brand and inward investment/business development functions are delivered from within just one organisation. In England, for example, Marketing Birmingham has latterly become a case in point, as has the East Mid lands city of Northampton through an agency known as Explore Northamptonshire.

In relation to the rest of the book, our organisational focus will be CTOs – all three kinds – as well as what we have referred to above as the CMA/CMIA forms of CMO. In Chapters 7 and 8 we will also consider the new breed of CBA which has recently emerged in Europe, especially in Germany and Holland. The typology presented in Figure 1.1 is, I believe, a useful starting point for a reader trying to come to grips with the otherwise arcane and sometimes perplexing organisational landscape represented by city tourism organisation. Another aid to understanding comes from tracing the historical origins and development of CMOs and CMAs, and it is this that we now discuss.

Evolution of City Tourism Organisation

Since time immemorial, there have been visitors to cities; the tourists have arrived and in their various ways been fulfilled, and for the city, there has been the resultant impact on economy, customs and landscape (de Botton, 2003). It can be argued that certain European cities such as Paris and London have been tourist destinations since as far back as Roman times. For sure, in the pre-industrial era the Grand Tour served as a finishing school for the British upper classes, connecting them with ‘cultural’ cities in Europe, amongst which were Paris, Rome, Turin, Basel, Berlin, Munich and Vienna (Black, 2003). Industrialisation and urbanisation in the 19th century to an extent shifted the focus of tourist movement from urban to rural, inducing a seasonal migration of humanity from town and city to sea and countryside. This movement of people came to symbolise leisure in the 19th and 20th centuries, and for Britain the classic account remains that of Pimlott (1947), as updated in several more recent books (e.g. Elborough, 2010; Walton, 1983).

While cities always remained significant for cultural and business tourism, it was not until the late 20th century that the focus of tourist movement began to shift once more in favour of the cities, reflected in a rapid expansion of convention, events and city break markets, both domestically and internationally. Key drivers of change were rising consumer affluence, low transport costs epitomised by carriers such as Ryanair and urban regeneration and reconstruction schemes. The latter not only boosted the touristic appeal of the long established ‘great’ cultural cities of Europe (Rome, Paris, Florence, Dubrovnik, Prague, Stockholm, Oslo, etc.), but also served to ‘reinvent’ industrial and/or war-damaged cities such as Glasgow, Warsaw, Rotterdam, Lodz, Birmingham, Barcelona, Genova and Dresden, emphasising their attractiveness as centres for business, culture, events, entertainment and shopping. A profound consequence of all of this, as we shall see amply demonstrated in the next chapter, is that the ‘great indoors’ of European cities are nowadays as sought after as the ‘great outdoors’ of coast and countryside.

The late 20th century also witnessed an upsurge of interest in city image and the related application of branding principles. To the best of my knowledge, this began in Europe in 1983 with the ‘Amsterdam has it’ and ‘Glasgow’s miles better’ campaigns, both cities endeavouring to emulate the success of the ‘I love New York’ logo and slogan which had been introduced during the previous decade. In North America itself, the first CTO developments came just over 100 years ago (Weber & Chon, 2002), and they provide a useful point of contrast and comparison with the situation that was to emerge in Europe. In the United States and Canada, CTO organisations were to label themselves visitor and convention bureaux (VCBs). Reputedly, the first was established for Detroit in 1896. Many more were to follow in the next two decades, including the San Francisco Convention and Visitors Bureau whose formation in 1909 was triggered by the earthquake and fire that had famously devastated the city three years earlier. Most North American VCBs were (and are to this day) private organisations, with the greater part of their funding coming from hypothecated local bed taxes levied on commercial accommodation providers. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the raison d’être of VCBs is the generation of additional overnight stay business for those self-same accommodation providers – to put ‘heads in beds’ as the saying goes in the industry. At a national level, the interests of North American VCBs have been protected and networked for well over a century by an influential trade association – the International Association of Convention and Visitor Bureaux (from 2005 renaming itself Destination Marketing Association International).

In comparison, the first European CTOs came into existence more sporadically than was the case in North America, and they were from the beginning a much less uniform product shaped by essentially local circumstance and need. Though the evidence base is sketchy and incomplete, it appears that in Europe, Switzerland led the way in creating CTOs/ CMOs. Certainly, the origins of what is now the Lausanne Tourism and Convention Bureau stretch as far back as 1866, and it may be regarded as Europe’s oldest surviving urban destination marketing organisation. During the last two decades of the 19th century, a clutch of Swiss CTOs arose covering Geneva (1885), Zurich (1885), Basel (1890) and Lucerne (1892). Similar developments occurred in other European countries. Sweden’s oldest city-based tourist organisation – the Gotland Tourist Association – was formed in 1896, bringing together tourism businesses and the municipality of Visby. A year later in Denmark, Copenhagen thought fit to establish a tourist promotional agency. In Holland, the antecedent of the ATCB is to be found in VVV Amsterdam; set up in 1902 to provide visitor information services in the Dutch capital. Over 100 years later, Amsterdam would be receiving nearly 5 million overnight stay tourists a year (see Chapter 2) and ATCB’s 2008 income would be €8.9 million, derived more or less equally between local authority grants (52%) and private sector contributions/trading (48%).

As collaborations of the municipal authority and the city’s tourism traders, these pioneering European CTOs foreshadowed what we have previously referred to as the public–private partnership, distinguishing them from their North American counterparts. In Europe, the prowess of public–private partnership as an organisational principle lay in a collective pooling of energies and monies across the public and private sectors which over time would lessen the burden on the local public purse – proportionately and, in some cases, absolutely. So, for instance, after a nearly 120-year history, Basel Tourism could in 2008 boast a multiplicity of local business partners, as well as an annual income of €7.4 million, of which only one-quarter derived from the local public sector. The remainder of the finances came from commercial membership fees (6%) and private sector contributions/trading income (69%). Similarly, the 2009 income of Lucerne Tourism amounted to €6.8 million, of which less than half (45%) derived from the public purse. Elsewhere in Switzerland, revenues from taxes on accommodation and other providers of tourist services have enabled the 125-year-old Geneva Tourism and Convention Bureau to be funded entirely from private sector and earned income sources. The Bureau’s budgeted income for 2010 is €9.2 million, over two-thirds of which (67%) is from tourist taxes levied on the local tourist industry and the remainder from earned income. In Europe, however, CTOs and CMAs funded entirely from private sources remain the exception rather than the rule. Moreover, even when this does happen, as is the case with the Geneva Bureau, close working relationships with the local public sector are still evident. Indeed, this Bureau describes itself tellingly as a ‘privately run public service association’. In addition to its mainstream conferencing, leisure tourism and visitor servicing operations, the Bureau through its events department is responsible for the city’s annual street party and musical extravaganza each summer (the Geneva Festival). For the record, Geneva registered 2.9 million tourist bednights in 2008, with annual accommodation occupancy standing at 66.2%.

Throughout the 19th century and for the greater part of the 20th century, CTOs and CMAs (as was the case with national- and regional-level destination marketing organisations) adopted marketing practices invented and pioneered for travel agencies and tour operators by Thomas Cook in 1841 (Delgado, 1977). In that year, Cook and his brother John organised the world’s first package tour, acting as an intermediary and connecting market to destination and venue through the medium of print. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, CTOs and CMAs were to act in just such a fashion as print-based intermediaries; conducting advertising campaigns, publishing brochures and measuring success by the number of coupon responses. The advent in the late 1990s of the ‘electronic age’ (foreseen and labelled ...