![]() Part 1: Collaboration and Tourism

Part 1: Collaboration and Tourism![]()

Chapter 1

Collaboration and Tourism

Introduction

In most industrial sectors it has become commonplace for organisations to collaborate in order to achieve the goals they have established for themselves. With the accelerating pace of technological innovation and the ever hastening trend towards globalisation, traditional adversarial relationships among business organisations are increasingly being swept away and replaced by enduring collaborative arrangements. This trend is particularly apparent in the tourism industry, where the fragmented, multi-sectoral and interdependent nature of tourism provides a powerful catalytic focus for inter-organisational co-ordination and collective decision-making. Tourism is a notoriously difficult industry in which to manage an organisation, and the increasingly competitive nature of the market relationships in which tourism organisations typically now find themselves does not make this management task any easier. Both at an international scale and locally, therefore, ‘tourism planners and operators are discovering the power of collaborative action’ (Selin, 1993: 218) and are moving away from the traditional ‘adversarial model’ of conducting business (Telfer, 2000: 72).

In few stages of the tourism ‘assembly process’ does any one company or organisation control all the components or all the stages of the decision-making process involved in the creation and delivery of the final product. As such, organisational performance is critically dependent on establishing and maintaining effective relationships, with organisations working collaboratively to serve the consumer. Indeed, some commentators even go so far as to suggest that successful collaborative relationships are an essential ingredient of organisational longevity in the tourism industry (Crotts et al., 2000; Haywood, 1992; Murphy, 1997).

A key reason for the growing interest in collaboration in tourism is the belief that organisations and destination areas may be able to gain competitive advantage by bringing together and sharing their combined knowledge, expertise, capital and other resources (Kotler et al., 1999b). If this is true, then the implication is that the more widespread adoption of collaborative working will be critical to the future of the tourism industry: firms and organisations will increasingly need to work together in order to meet the needs of the customer, in this instance the tourist. Meanwhile, rapid economic, social and political change also provides powerful incentives for tourism organisations to concede their independence and collaborate with one another. Osborne and Gaebler (1992), for example, argue that the divide between the public and private sectors is becoming increasingly nebulous, encouraging organisations that were previously isolated from one another to begin working collaboratively. They also point to tightening budgetary constraints, combined with political and public pressure for greater accountability, as key incentives for collaboration in the tourism industry.

Interest in collaboration in tourism has arisen at a time of increasing environmental turbulence and operational complexity for organisations of all kinds, particularly since the terrorist atrocities committed in New York and Washington, DC on 11 September 2001 (now widely referred to as ‘9/11’). The transition to alternative forms of collaboration, in particular strategic alliances, has been recognised by organisational theorists and practitioners alike, and has intensified scrutiny on all issues ‘collaborative’ (Long, 1997). For example, collaboration is now widespread in many public tourism initiatives, especially in the European Union (EU) where funding for many urban and regional regeneration projects demands collaboration as a precondition. Collaboration also represents a ready ‘bridge’ between the traditional ‘bureaucratic’ production culture of the public sector and the ‘marketing culture’ of the private tourism sector (Palmer, 1996). Arguably, in many instances it is the lack of a marketing culture in the public sector that has motivated collaboration with private-sector organisations, the aim being to gain access to core competencies in marketing and related activities. Waddock (1989) supports this viewpoint by stating that the private sector generally has a much greater commitment to a market orientation, which it can exchange for access to the public sector's political and economic resources, which cannot be obtained on the open market.

In spite of the above rationale, and regardless of the existence of considerable environmental pressures, the intrinsically competitive nature of tourism has not always assisted in the development of effective collaboration among tourism organisations. This tendency has been particularly evident at the local level. Unsophisticated communication systems, endemic geographical and organisational fragmentation, issues pertaining to jurisdictional boundaries and the ideological divide between public and private sectors have often inhibited the adoption and implementation of effective collaborative tourism initiatives.

It may therefore be considered surprising that, although the subject of collaboration has been researched in depth in the fields of health, organisational behaviour, corporate strategy and public policy, its emergence on the tourism research agenda is still relatively recent. Publications by Crotts et al. (2000), Palmer (1998b), Palmer and Bejou (1995) and Selin (1993) have contributed much to greater understanding of the issues, actions and implications of collaborative behaviour in tourism. However, the study of collaboration in the tourism context nevertheless remains in its academic infancy, both in respect of tourism generally and applied to tourism marketing in particular. Long (1996), for example, claims that there is a distinct lack of studies that employ theoretical frameworks and methods associated with the analysis of collaboration in tourism, while Pearce (1992) suggests that limited research has been conducted on tourist organisations per se. In a more recent publication, Bramwell and Lane (2000: 3) argue that ‘despite increasing interest in tourism partnerships, until recently there has been little systematic research on the internal processes and external impacts of these organisational forms’.

A central argument being put forward in the present text is that questions directed at co-ordination and inter-organisational interaction are critical, indeed fundamental, to the future analysis of tourism and tourist organisations. Moreover, Jamal and Getz (1995) suggest that, in view of the interdependencies and the simultaneous use of competitive and collaborative strategies in tourism, the various stages and actual implementation of the collaboration process require investigation. The time has truly arrived where a paradigm shift is required in the study of tourism and, in particular, the study of tourism marketing. It is clear that the focus of academic concern now needs to shift from the individual ‘competitive’ organisation to the inter-organisational ‘collaborative’ domain (meaning the configuration of organisations linked to a particular shared problem). This shift is likely to be hastened by the considerable economic, social and political pressures that are encouraging tourism organisations to relinquish their autonomy and to participate in collaborative decision-making. Indeed, as Go and Appelman (2001) note, collaboration is now widespread in the tourism domain. The number and variety of inter-organisational collaborative relationships and networks has grown significantly over the past two decades, and the pace of change is clearly increasing. Those interested in the management and marketing of the tourism industry misunderstand the dynamics of collaboration at their peril. Collaboration, in all its many forms, is not only integral to the management of tourism; it is arguably the single most important aspect of management in determining the success, or indeed the failure, of tourism marketing strategies and programmes. What is more, collaboration looks set to maintain such primacy for many years to come.

Drivers of Collaboration

The foregoing discussion has highlighted the increasing tendency for organisations to adopt collaborative strategies to address problems that have traditionally been considered to be ‘competitive’ in nature. The purpose of this section is to consider the major forces that have driven the emergence and acceptance of collaborative strategies both in the tourism context and in business more generally.

Globalisation

Many writers propose that the predominant force acting on the world's economic systems at the present time is that of globalisation (for example, Levitt, 1983; Ohmae, 1989; Yip, 1993). Indeed, it is rapidly becoming untenable even to speak of more than one economic system in the world. The process of globalisation has broken down the barriers between economic systems and encouraged them to become progressively more integrated with one another. The result has been the emergence of what can increasingly only be described as a single global economy.

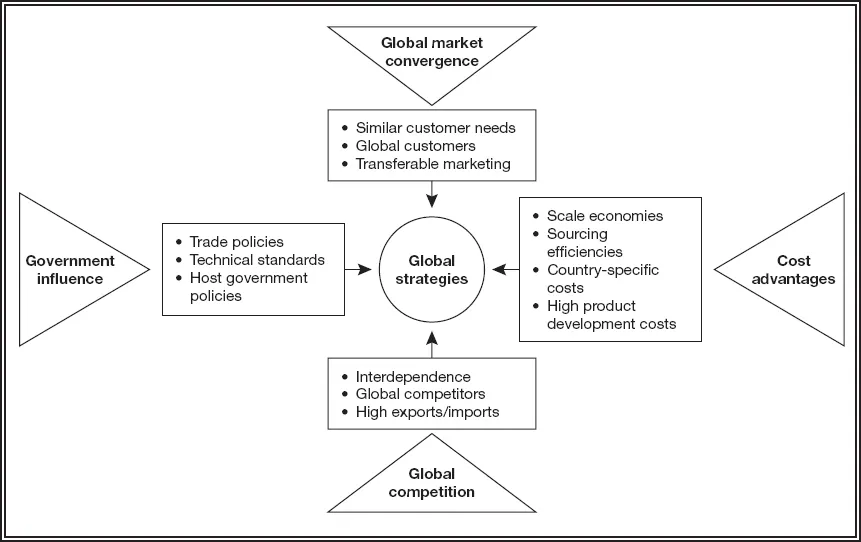

Globalisation has been, and continues to be, driven by an array of converging forces. Figure 1.1 identifies those forces identified by Yip (1995) as some of those central to the emergence of globalisation as the world's predominant economic order. Advances in information technology, communication methods and distribution systems, along with continued economic growth in the developing world, have all contributed greatly. Likewise, policy changes in many countries around the world and the emergence of transnational corporations – the so-called new vistas of competition (Ohmae, 1991) – are also reinforcing the trend towards globalisation.

There can be little doubt that globalisation has substantially raised the level of competition in many markets, many business organisations now having to compete in a much more complex and multi-faceted economic environment. Indeed, Wahab and Cooper (2001: 4) suggest that globalisation has now become an all-embracing term that denotes a world which ‘due to many political, economic, technological and informational advancements and developments is on its way to becoming borderless and an interdependent whole’. In the specific context of tourism, Wahab and Cooper go on to suggest that the continuing growth in demand for tourism, the expansion and diversification of travel motivations and the enlarged expectations of tourists are all contributing to the increasing global presence and significance of tourism in the world economy. Fierce competition between an increasing number of tourist destinations and a trend towards increasing deregulation in many of the world's tourism industries are also contributing to a more globalised environment in which the business of tourism is conducted.

Figure 1.1 Drivers of globalisation

Source: Based on Yip, 1995

Globalisation is leading to an increasingly borderless and interdependent world, and this serves as the catalytic focus for much collaborative activity, both within the tourism industry and outside it. Magun (1996) argues that across all industrial sectors there is growing acceptance that competition itself does not necessarily promote optimum, innovation-led growth. The realisation is that both competition and collaboration between organisations is now needed to ensure survival and growth in an increasingly uncertain and dynamic world. Armed with new strategies, both competitive and collaborative in nature, business organisations are now able to penetrate formerly inaccessible markets and take advantage of the opportunities afforded to them by globalisation. This is true for industries as diverse as pharmaceuticals and petrochemicals, automotive and semi-conductor manufacturing, financial services and the provision of health and educational services. Magun's explanation for this trend is that the need for complementary specialised inputs has forced organisations to change their business strategies by embracing collaboration. This has enabled them to create added organisational flexibility in their value chain activities, such as research and development, and in logistics and channels of distribution.

The socio-economic, cultural and political forces of globalisation are such that one can argue that an international ‘global society’ is not just in the making, it is already with us. Moreover, for many writers, the trends presently being established do not look set to abate in the foreseeable future. If anything, they look set to accelerate rapidly in the years to come. This is an issue emphasised by Gartner (1996), whereby change is argued to be taking place at such a prolific rate that policy and decision makers are under considerable pressure to change their attitudes and previous beliefs and policies in order to keep abreast of basic socio-economic, cultural and political values and norms.

Forces are one thing; reacting to them is another. For the tourism industry, the most influential factors associated with globalisation are significant changes in consumer tastes and expectations, and the development and adjustment of new integrated corporate structures as a result of alliances, mergers and acquisitions. Whereas horizontal and vertical integration in the tourism industry started in the 1960s, intensifying through the 1960s and 1970s, the globalisation era is mainly characterised by diagonal integration. Designed to get closer to the consumer and reduce transaction costs through economies of scope, system gains and synergies, this trend is now well established and widespread. For example, Domke-Damonte (2000) identifies the increasing propensity for diagonal collaborative relationships to be established between airlines, hotels, restaurants, mortgage companies, rental car companies and credit card providers, all of which are important constituent elements of the tourism product.

Given the enormous power and reach of globalisation as a driving force in the business environment, Kanter (1995) argues that the criteria of success for tourism organisations in a globalised society are changing. Kanter suggests that in the future tourism organisations will be judged increasingly on the quality of their concepts (leading-edge ideas, designs and product formulations), on their competencies (their ability to deliver products and to transform ideas into services) and, above all, on their connections. The notion of ‘connections’ relates to the organisation's collaborative networks, that is, the alliances and relationships that lever core capabilities, create value for customers and remove boundaries. Global airline alliances are just one example of such new inter-organisational forms in the era of globalisation.

International political and trade agreements

An important factor contributing to globalisation, and clearly also to the emergence and accelerated growth of inter-organisational collaboration, is the proliferation of trade agreements and new inter-nation forms of political integration. The recent accession of 10 new member states into the EU, and the entry of former Eastern Bloc countries such as Hungary and Romania into the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), are both witness to the success of t...