![]()

Part 1

Changing Places: The Local and the Global in Tourist Communities

![]()

Chapter 1

‘If It Wasn’t for the Tourists We Wouldn’t Have an Audience’: The Case of Tourism and Traditional Music in North Mayo

MOYA KNEAFSEY

Introduction

Traditional music is often used as an important, if contested, signifier of Irish national identity. For instance, Ireland is one of the only countries in the world to have a musical instrument, namely the harp, as its national symbol (Vallely, 1999). Contemporary tourism images, appearing in brochures, postcards and books, reinforce the association of Ireland with traditional music and dance and encourage tourists to expect at least some exposure to the sounds of the nation that produced Riverdance. This expectation is enhanced through television travel programmes about Ireland that inevitably portray mountains, lakes and empty beaches accompanied by the wistful strains of the pipes or whistle and show musicians playing in a cosy local bar, pints of Guinness prominently displayed.

Not only are visitor numbers to Ireland increasing at a rapid rate, with a massive 7.1 million tourist arrivals predicted by 2003 (Bord Fáilte, 1998) but the audience for various forms of recorded ‘Irish music’ is also growing (Thornton, 2000). There has also been a huge increase in the number of summer schools and festivals offering classes and competitions in a wide variety of instruments, singing styles and dance, as well as lectures, recitals and pub music sessions. One of Dublin’s newest tourist attractions is Ceol, described as an ‘interactive Irish music encounter’ and ‘a celebration of a living tradition’. Similarly, the Dublin musical pub crawl has proved highly popular, with tickets being sold to approximately 6–7000 tourists a year (Quinn, 1996). Not only does traditional music, therefore, act as a general backdrop to various representations of Ireland but there is evidence to suggest that significant numbers of people include listening to or playing traditional music within their holiday activities.

Despite the growth of tourism in Ireland, the evident interest in traditional music on the part of tourists and the gradual recognition that music can be a valuable component of the Irish tourism product, little research has been published on the relationship between tourism and traditional music. Indeed, this may be indicative of a more general ‘absence of critical discussion’ of the subject of tourism in Ireland (O’Connor & Cronin, 1993). Yet the interface between tourism and traditional music raises a whole series of questions regarding the impacts and sustainability of cultural commodification, the ways in which visitors and local people construct meanings of authenticity and tradition and the ways in which tourism influences shifting geographies of musical production and consumption. My aim in this chapter, therefore, is to present an introductory discussion of some of these issues through a focus on just one aspect of the traditional music–tourism relationship, the pub ‘session’. This is probably the setting in which most visitors to Ireland consume the performance of live traditional music and it is an interesting cultural practice to examine in that it retains a sense of spontaneity and mystique which distinguishes it from many contemporary forms of entertainment. The discussion is based on fieldwork undertaken in North Mayo and should be seen as an attempt to, first, prompt further research on this rather neglected topic and, second, contribute to the development of a theoretically-informed body of work investigating the sociocultural and economic influences of tourism in Ireland more generally. In order to do this, I draw on notions of ‘culturalisation’, commodification and recent theories of the construction of musical meanings. Using these ideas, I suggest that during the summer season, symbiotic relationships between musicians, tourists and publicans are constitutive of the meanings attached to the pub sessions held in North Mayo. However, the summer session is gradually being re-defined as a ‘gig’ and these delicate relationships of symbiosis may be replaced by formalised relationships between ‘performers’ and ‘audience’. This increased formalisation, however, does not necessarily indicate the complete commodification of this cultural practice. Rather, it is necessary to recognise that some of the socio-musical meanings that are currently attached to the session by locals, publicans and musicians enable it to ‘defy’ or evade commodification in any consistent sense.

The Traditional Music and Tourism Interface: Conceptualising Complexity

Traditional music is the older dance music and song in Ireland. According to the Irish Traditional Music Archive (Vallely, 1999: 403) it is, above all, the music of a living popular tradition. It incorporates a large body of material from the past but this does not form a static repertory – rather it is always changing through shedding material, the re-introduction of neglected items and the composition of new items. Change, however, is slow and takes place within generally accepted principles. It is essentially oral in character in that song and instrumental music have been carried in memory – largely independent of writing and print. Even today, with more printed music available, most musicians learn through imitating more experienced performers. Within this context, the session functions as an important opportunity for musicians to meet and exchange tunes. Although it may be popularly perceived as a very old and thus ‘authentic’ cultural practice, playing together seems to have happened first amongst emigrant musicians in early 20th century America. Pubs generally became an important feature of Irish social life only after the Second World War and from the late 1940s, emigrants imported the idea of sessions from Irish pubs and clubs in England. The session began as a purely amateur event but around the mid-1970s publicans began to pay one or two musicians to turn up on a regular night. It is estimated that there are now more than 1500 pub sessions weekly, many in some way commercial, with half of them running throughout the year (Vallely, 1999).

Whilst research has been conducted into the revival of local festivals (Aldskogius, 1993; Boissevain, 1992; Ekman, 1999), relatively little work has focused specifically on the use of music as a tourist attraction. In the case of Ireland, Quinn (1996: 393) has conducted preliminary work on blues, arts and opera festivals, but affirms that it is ‘[A] difficult task, and one which requires extensive further research attention, understanding the nature of the music–tourism relationship, and in particular, understanding how music is affected in the process of tourism consumption’. The conceptualisation of the relationship between tourism and traditional music presents a considerable challenge, not least because both practices can be theorised from a multitude of perspectives drawing from a variety of disciplines including tourism studies, cultural studies, sociology, geography, anthropology, ethnomusicology and popular music studies. Furthermore, as Lau (1998: 116) argues, ‘we must recognise from the outset that a universal theory of tourism is highly impractical and virtually impossible because the nature and mode of interaction between society and tourism varies significantly from place to place’. He continues that the study of tourism should be grounded in the ‘context and specificities dictated by particular social and historical conditions’. Recognising this, I propose some initial conceptual foundations upon which an understanding of the relationship between tourism and traditional music in just one place in Ireland might be constructed. I suggest that starting points can be found in the literature concerning cultural tourism, cultural commodification and the construction of musical meanings.

The ‘Culturalisation’ of Touristic Practices and the ‘Commodification’ of Cultural Practices

A useful point of departure is provided by Rojek and Urry (1999), whose underlying aim is to demonstrate that tourism is a cultural practice and that tourism and culture hugely overlap. For instance, they note the increased ‘culturalisation’ of tourist practices, which is most obviously seen in the growth of ‘cultural tourism’. In Ireland, cultural tourism has been particularly developed in the form of heritage attractions, interpretive centres, parks and monuments (O’Donnchadha & O’Connor, 1996). However, traditional music is now being recognised as an important part of the tourism product and a recent report (Ó Murchú, 1999) recommends a comprehensive assessment of the potential of Irish traditional music, song and dance in cultural tourism. Interestingly, July 2000 saw the re-introduction of ‘Seisiún’, a nationwide scheme of traditional music and dance, for the first time in over a decade. Organised by Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, the aim of Seisiún is to help visitors to find the ‘hidden Ireland’ by providing a ‘music trail’ of ‘native entertainment’ in specified locations across the country over a seven-week summer period.

The current chapter is concerned with the following question: What are the impacts of the increased ‘culturalisation’ of touristic practices upon existing cultural practices? This question is usually framed in terms of debate over the commodification of culture and resulting issues of authenticity, meaning and ownership. Craik (1997) for instance, asks whether culture has merely become a convenient marketing ploy or whether a fundamental change in the nature of tourism has occurred. Her central argument is that any modification of the culture of tourism is only short term. Drawing on the work of Silberberg (1995), she casts doubt on the existence of many ‘true’ cultural tourists and suggests that, in fact, a significant number of tourists are actually ‘culture-proof’. Furthermore, cultural tourism incurs disbenefits that will undermine rather than enhance recent governmental and institutional commitments to cultural development. One of the reasons for this is that the cultural experiences offered by tourism are consumed in terms of prior knowledge, expectations, fantasies and mythologies ‘generated in the tourist’s origin culture rather than by the cultural offerings of the destination’ (Craik, 1997: 118; emphasis in original). In short, she implies that cultural tourism developments can threaten longer-term cultural integrity. There is a sense that market values subsume everything and local people risk losing the ‘authentic meanings’ of their culture by performing for outsiders.

Countering this view, some more recent local-level studies demonstrate that issues of meaning, ownership and power relations are important in discerning whether cultural integrity – however this may be defined – is maintained. Lau (1998), for instance, demonstrates that in the Chinese context it is important to examine the different ways of understanding the term ‘traditional’. To Chinese musicians the term is applied to any music that has existed for a period of time and this is reflected in concert-playing styles and repertoire. This is in contrast to western connotations of ‘authentic’, ‘pure’ and ‘ancient.’ Lau suggests that the majority of tourists do not know about this difference in emphasis or its implications for performance. Rees (1998), however, problematises this assumption by pointing to the existence of tourists dismayed by professional troupes and in search of more ‘traditionalist’ concerts. Nevertheless, from the Chinese perspective, control over the content of cultural production remains firmly with the hosts. Importantly, Lau also highlights the ways in which tourist performances are intertwined within the Chinese state’s perception of post-Mao nationhood and modernity and local perceptions of identity. Lau’s focus on contextualising tourism within the ‘social and historical moment’ is important, although the resulting account has a structuralist flavour, whereby performers are conceptualised as ‘actors’ or ‘players’ in the ‘show whose script is written in the narrative of society’. There is a sense that performances are ‘determined’ and ‘pre-disposed’ by the political economic and social forces at work at national and global levels. I hope to develop a more fluid interpretation whereby the meanings of cultural productions are seen as being continually constructed and contested through processes mediated by individuals and institutions operating at multiple geographic scales. The key strength of Lau’s work is his attention to the meanings that are attributed to music by performers and I argue that this provides a clue to understanding the impact of the ‘culturalisation’ of tourism in the sphere of Irish traditional music. More specifically, it is necessary to focus on how musical meanings are constructed through the complex interplay of tourists, musicians, publicans and local residents.

The Construction of Musical Meanings

Some powerful theoretical insights into this process are provided by Revill’s (1998) work on hybridity, identity and networks of musical meaning. He draws on Actor–Network Theory to argue that ‘musical meaning is produced through a cultural geography consisting of heterogeneous networks of practices, institutions and artifacts that together make music at once an imagined and a material entity’ (p. 198). Specifically, he refers to Michael Callon’s thesis that all human and nonhuman entities are potential actors, which have ‘the capacity to make connections with others, thereby producing networks of social meaning’ (p. 201). Revill proposes that this approach is useful for the study of music because ‘it enables the diverse elements of musical communication – from patterns of sound and embodied gestures, to technical skill in instrumental virtuosity or dance, to written scores, to theoretical treatises, to recordings of performances – to be considered together as mutually constitutive of musical meaning’ (p. 202). Music is thus always both at once a social and a technical activity. Revill suggests that one of the most controversial aspects of Callon’s work – the idea that all intermediaries, human or non-human, have agency – is best interpreted as ‘a set of potentialities that reside in the nature of the object rather than any form of self-reflexive action’ (p. 211). This can be described as ‘a tendency towards multivalency that allows the artifact …to resist or escape definition within any particular network’. This relates most closely to the quality of music, which, in Said’s words, allows it to ‘travel, cross over, drift from place to place in a society, even though many institutions and orthodoxies have sought to confine it’ (cited by Revill, 1998: 211). This point can be illustrated through reference to the contested history of traditional music in Ireland. Different actors have struggled to attach different meanings to a cultural practice which has enormous mobility. For instance, to many clergy in the early decades of the 20th century, it was seen as an accessory to immoral social behaviour. At the same time, some politicians associated it with subversive political activities such as raising funds for the IRA. They combined to pass the Public Dance Halls Act of 1935, which introduced strict licensing controls which, according to critics, almost resulted in the eradication of music and dance in some areas. At the same time, traditional music also faced competition from fashionable new music imported from America and England. In contrast to these modern, urban cultural practices, traditional music was denigrated by many as the expression of unsophisticated and primitive country folk (Vallely, 1999: xv). Nevertheless, the 1960s era of protest songs and civil rights movements saw a revival of interest in traditional music. This, in itself, prompted another battle for definition, as musicians tried to distinguish ‘authentic’ Irish music from popular folk song (e.g. Bob Dylan), Irish ‘ballad groups’ and political ballads. More recently, traditional Irish music has experienced another surge in popularity, this time re-defined in the context of a new, highly commercialised ‘Celtic craze’, which began in the late 1980s (Hale & Payton, 2000).

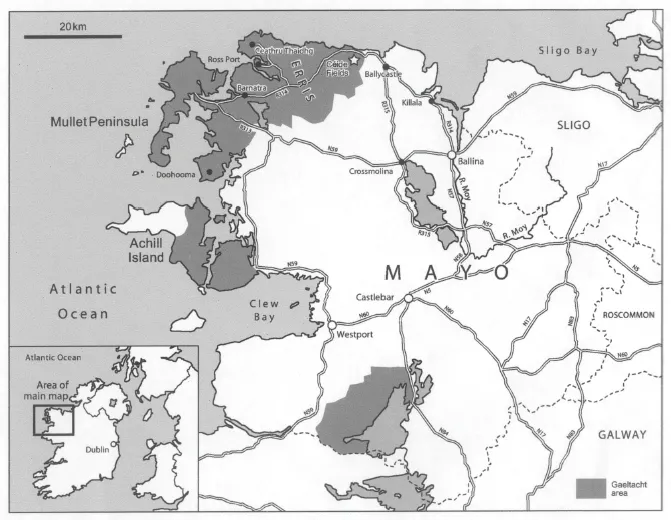

There is thus a long and complex history of struggles to define, defend or control the meaning of ‘traditional music’. This history illustrates the ‘ability of music to escape or defy the meanings assigned to it’ (Revill, 1998: 212). The point is that any consideration of what happens to traditional music when it is juxtaposed with tourism must take into account the intricate relationships through which musical meanings are (de/re)constructed. In order to open up these complex issues in relation to some empirical research findings, I now turn to the case of traditional music sessions in North Mayo. For the purposes of this research, I decided to focus on the three coastal towns of Ballycastle, Killala and Ballina (see Figure 1.1). This was partly dictated by the availability of sessions but it also allowed me to build upon qualitative research already conducted on aspects of tourism, culture change and identity in North Mayo (Kneafsey, 1998, 2000). Crucially, it enabled me to draw on experiences and knowledge gathered over a decade of playing in sessions during fieldtrips and holidays to the area. The main research techniques were participant observation at sessions during the summer of 2000, plus qualitative interviews with musicians, publicans and tourists.

Figure 1.1 The study region of north Mayo

Introducing North Mayo: Tourism and Musical Practices

County Mayo as a whole is firmly located, both geographically and symbolically, in the West of Ireland. This region has, over time, been portrayed as a repository of national identity (Nash, 1993), the heartland of linguistic and cultural traditions. According to Bord Fáilte statistics, the county received 288,000 out of a total of 1,071,000 overseas tourists to the West Region (covering Counties Galway, Mayo, Roscommon) in 1998. It is estimated that this generated IR£50 million in revenue against a total of IR£236.6 million for the West Region as a whole (Bord Fáilte, 1999). Although tourism development in County Mayo has concentrated around the hotspots of Westport and Achill, there has been a discernible growth in the number of visitors to North Mayo, especially to the towns of Killala and Ballina. The latter, in particular, now offers an improved range of accommodation facilities and both towns also host heritage days at which traditional music features prominently. The situation is different in areas further West. Despite the flagship Céide Fields Visitor Centre, which in 1998 received 40,104 visitors (Tourism Development International, 2000), the scenic stretch from Ballycastle to Ceathru Thaidhg provides few facilities for tourists and remains relatively inaccessible. The area suffers from a lack of adequate basic infrastructure such as good roads, consistent water supplies and reliable waste treatment facilities. Although the county population is becoming increasingly urbanised, North Mayo is still a predominantly agricultural and rural area, which supports small and comparatively isolated communities, including those in the fragile Erris Gaeltacht. In fact, as urbanisation proceeds at an ever faster rate around the main population centres, these areas seem increasingly marginalised in comparison. According to census figures, the number of people employed in agriculture, farming and fishing has fallen substantially from 13,206 in 1981 to 7963 in 1996. Unfortunately the census does not show numbers employed in tourism but the estimated 32,090 employed in tourism in the West Region gives some idea of the relative importance of the industry (Tourism Development International, 2000).

The Music and Musicians of North Mayo

Although never as renowned as the East Mayo–Sligo border area, with its well-documented tradition of fiddle and flute-playing, nor the more recently famous town of Westport, North Mayo was once well known for its melodeon players. Up until the 1930s traditional music was strong in Mayo but then a number of factors militated against it, as in other areas of Ireland. These included the Dance Halls Act (Vallely, 1999), the growth of show bands and emigration. With 111,524 inhabitants in 1996, the county has never recovered its pre-famine population of 388,887 in 1841. The impact of mass emigration on the musical life of small rural communities cannot be underestimated – most of the noted Mayo musicians of the early 20th century emigrated to America or England. This long history of emigration has an important ‘feedback’ effect, in that many visitors to the county are, in fact, ‘exiles’ returning home. Many of them are of a generation that...