![]()

Part 1

Context

![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: Second Homes, Curse or Blessing? Revisited

C. MICHAEL HALL AND DIETER K. MÜLLER

Second homes are an integral part of contemporary tourism and mobility. In many areas of the world, second homes are the destination of a substantial proportion of domestic and international travellers, while the number of available bed nights in a second homes often rivals or even exceeds that available in the formal accommodation sector. For many destinations, particularly in more peripheral areas, second homes are a major contributor to regional economies, while they may also represent a significant heritage resource because of their use of vernacular architecture and the ongoing use of buildings that may otherwise have fallen into disrepair. At the level of the individual, second homes may also be important for concepts of identity and sense of place, particularly as they may represent a connection to family and/or childhood place affiliations. All this is not to say that second homes are universally welcomed. In some areas, second homes are seen as putting further pressure on existing housing stock and forcing up prices, thus making it harder for permanent residents to obtain housing. Similarly, where there are substantial seasonal variations in second home use, these may be perceived as exacerbating seasonal patterns in employment and economic demand, rather than assisting with regional development strategies. Finally, in some circumstances second home households may be seen as outsiders and even as invaders, which at times has created substantial resentment, even leading to destruction of the second home property. The various dimensions of second home development point to both the complexity and significance of the subject. This book therefore aims to explore such complexities with the aim of providing an informed contribution to the debate as to the value and significance of second homes.

The present chapter provides an introduction to the concept of second homes and discusses its historical and spatial characteristics as well as some of the motivations of second home ownership. One notable point in examining second homes is that, in comparison with some other areas of tourism and leisure mobility, they have a relatively long history of scholarship, often within particular national traditions. In the case of Scandinavia Ljungdahl (1938) was reporting on second homes in the Stockholm archipelago before the Second World War. This study was followed up in the 1960s and early 1970s by such researchers as Aldskogius (1968, 1969), Finnveden (1960) and Bielckus (1977). In North America second home research was pioneered by the work of Wolfe (1951, 1952, 1962, 1965, 1977) in Canada (see also Lundgren, 1974), with substantial early research also being undertaken in the United States (Ragatz, 1970a, 1970b; Ragatz & Gelb, 1970; Burby et al., 1972; Clout, 1972; Geisler & Martinson, 1976; Tombaugh, 1970). Continental Europe also witnessed a significant amount of early research (Barbier, 1965; Cribier, 1966, 1973; David, 1966; David & Geoffroy, 1966; Clout, 1969, 1971, 1977; Grault, 1970). Nevertheless, it was the publication of Coppock’s (1977a) book Second Homes: Curse or Blessing that was to provide a benchmark for second home research, reflecting as it did contemporary debates over the value of second homes, especially bearing in mind the substantial opposition to second homes in some parts of the United Kingdom, Wales in particular (Coppock, 1977b; Rogers, 1977). Yet despite the significance of Coppock’s (1977a) publication, somewhat ironically, relatively little was published on second homes in the late 1970s and early 1980s, leading Whyte (1978) to enquire, ‘Have second homes gone into hibernation?’ Indeed, it was not until the later part of the 1980s and the 1990s that a substantial number of publications on second homes once more began to emerge. There may have been several reasons for this re-emergence:

(1) the growth in inter-regional and international second home related retirement migration;

(2) increased recognition of the economic, environmental and social implications of tourism by government;

(3) the deliberate use of second homes as an economic development tool; the re-emergence of conflict between second home development and permanent populations in some localities, making second homes a significant policy issue.

The present book takes stock of much of this second wave of second home research, but the contributors to this volume are mindful of much of the pioneering work of Coppock (1977a) and contributors, and the substantial insights that they demonstrated on tourism, which we now have the opportunity to revisit.

Defining Second Homes

There is a great variety of terms that refer to second homes: recreational homes, vacation homes, summer homes, cottages, and weekend homes. In the context of this book, the term ‘second home’ is used as an umbrella for these different terms, which all refer to a certain idea of usage. It should be noted that the term ‘cottage’ which is also used in this book (Halseth, Chapter 3; Svenson, Chapter 4) does not primarily address the physical form but the function of the second home, usually referring to small houses that are mainly for recreational use. Similarly, second homes can also be apartments.

Table 1.1 Second home characteristics

Type | Structure | Buildings/Vehicles |

Non-mobile | Houses and apartments | Solitary cottages and houses Second home villages Apartment buildings |

Semi-mobile | Camping | Trailers/mobile homes Recreational vehicles Tents Caravans |

Mobile | Boats | Sailing boats |

Source: Newig (2000)

In contrast to other forms of tourism mobility, such as day tripping, second home tourism is covered relatively well in census data and national statistics. Nevertheless, there is a lack of comparable data, for example because of different national definitions as to what constitutes a second home. For example, in some jurisdictions caravans and boats may be regarded as second homes (Coppock, 1977c; Newig, 2000), while in others (Keen & Hall, this volume) unoccupied houses in rural areas are not officially classified as second homes and have to be occupied on census night in order to be officially recognised. Three groups of second homes may be recognised: stationary, semi-mobile; and mobile (Table 1.1). However, most researchers employ a pragmatic approach where data access determines the definition of second homes. Therefore, the primary focus is on non-mobile second homes. Furthermore, although time shares demonstrate some similarities with second homes, they are not usually included in second home data (although see Timothy, this volume). In addition, although urban second homes exist, they have not generated significant attention because they are relatively few in number. Instead, focus has long been placed on second homes in rural and peri-urban areas, and this book, too, focuses on privately-owned rural second homes.

Definitional approaches to second homes are also made more complicated because interest in second homes is not limited to tourism research, and has attracted attention from urban and regional planning (Langdalen, 1980; Gallent, 1997; Gallent & Tewdwr-Jones, 2000), rural geography (Pacione, 1984; Buller & Hoggart, 1994a) and population geography (Warnes, 1994; King et al., 2000). This is also mirrored in the terminology used to characterise second home tourism. For example, Casado-Diaz (1999) uses the term ‘residential tourism’; Flognfeldt (2002) prefers ‘semi-migration’, Finnveden (1960) ‘summer migration’, and Pacione (1984) writes about ‘seasonal suburbanisation’.

The Nature of Home

To complicate definitional matters further, both the term and the concept of second homes have been increasingly brought into question (Kaltenborn, 1997a, 1997b, 1998; Müller, 2002c) by the growing number of households in the developed world with the ability to allocate their time independently of a single workplace, and so are able to adopt more mobile lifestyles, and may have several homes (Williams & Hall, 2002). Kaltenborn (1998) argues that second homes are seldom sold, but are sometimes passed on through generations. Hence, they may form a first home because of the strong emotional place attachment of their owners, and Kaltenborn (1998) uses the term ‘alternate home’ to indicate the emotional meaning that is otherwise hidden by the term second home. The extent of this phenomenon, however, is often concealed owing to administrative practices that require households to register a primary residence (Müller, 2002c).

Müller (2002c) criticises the administrative practices that fail to recognise the complexity of current mobility patterns and forms. Departing from Williams and Hall’s argument (2000a, 2002) Müller argues that neither space–time use nor the motivations for mobility are sufficient indicators to distinguish tourism from migration. Hence, whether a house is a primary residence or a second home is entirely the owners’ decision. This decision can depend on a variety of factors, such as local taxation rates and the order in which homes are purchased. However, evidence also suggests that the most owners are hardly aware of the consequences of this decision (Williams & Kaltenborn, 1999; Müller, 2002c).

In reality, it can be predicted that a considerable number of people have more than one place that can be called a home. However, practical matters concerning, for example, taxation, statistics, voting and other citizenship rights force individuals and households to state exactly where they are at home. This administrative practice clearly fails to acknowledge the complexity of life and mobility by defining people as static and immobile in their day-to-day everyday life (Müller & Hall, 2003). Administrative procedures simply do not accept that people are at home in two places at once, in the same way that travel arrival cards usually do not allow more than one reason for a visit. Setting the notion that individuals are mobile against this bureaucratic background is not a trivial concern. In fact, in many ways the term second home has arisen as a result of these administrative practices. In many jurisdictions, the power of such practices may be so significant as to exclude second home owners from some of the local community institutions and practices. In this respect, the term second home may provide an additional meaning as it may identify second home owners and households as only partial members of the local community when it comes to the ability to participate in certain rights and duties.

The consequences of this practice can be significant not only for the single individual, but also for the local communities. Having only a second home rather than a primary residence in some communities may mean that the second home owners are excluded from certain citizenship rights by virtue of their capacity to vote, and from access to some public amenities and institutions. Accordingly, they may not be able to influence the local society to the same extent as ‘permanent’ residents. Such regulatory barriers may also serve to reinforce the perception in some circumstances, for example, that they are outsiders who can be accused of displacing ‘real’ locals from the housing market (Gallent & Tewdwr-Jones, 2000). Moreover, they may be perceived as temporary residents, even though they might live there more than six months a year and thus spend more time in the host community than ‘permanent’ residents (Müller, 1999; Flognfeldt, 2002). Indeed, in some countries the local community tax income and other public transfers depend on the number of ‘permanent’ residents, which does not necessarily correspond to the actual number of residents (see Chapter 2). In other jurisdictions, second home owners may pay local community taxes but not be allowed the right to vote. The number of residents, ideally expressed as the result of an equation that represents the actual time spent in the community by ‘permanent’ residents and second home owners, is usually unknown (Müller & Hall, 2003). Nevertheless, the lack of appropriate measurements and statistics can be mirrored, for example, in a deficit of local service provision (see Frost, this volume) or in disagreement over what the actual level of service provision should be (Keen & Hall, this volume).

The Historical Geography of Second Home Tourism

The origin of second homes can be traced back to ancient societies where the house in the countryside was an exclusive asset for the nobility (Coppock, 1977c). During the 18th century, second homes could be found in spa towns and later in coastal towns (Löfgren, 1999) and were often used on a seasonal basis to escape city life. New means of transportation had a substantial influence on the geography of second homes. In the Stockholm archipelago, for example, second homes were built along the steamboat lines (Ljungdahl, 1938), and Flognfeldt (this volume) has noted a similar pattern of development along the Oslo Fjord. During the first part of the 20th century, second home ownership spread to other groups outside the upper classes together with changed ideas regarding contact with nature and wilderness. In North America, second homes were constructed in wilderness areas, partly as a cultural reminder of frontier development (Coppock, 1977c; Wolfe, 1977; Löfgren, 1999). In New Zealand and Australia many of the first coastal second homes were little more than fishing huts on public land (Selwood & Tonts, this volume; Keen & Hall, this volume) that provided households with cheap holidays by the beach and an escape from the warmer inland areas. In the Nordic countries, second home construction was supported as a mean of social tourism and entailed the construction of a large number of second homes in metropolitan hinterlands, particularly between 1950 and 1980 (Nordin, 1993b).

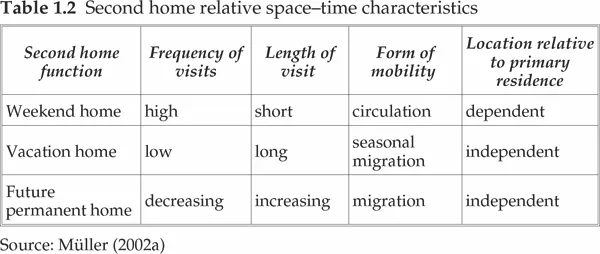

However, the main increase in second home ownership since 1960 can be explained by the increased personal mobility offered by growing car ownership and access. The idea of owning a weekend refuge for relaxation contributed to the development of second homes within easy access of urban areas (Wolfe, 1951; Lundgren, 1974; Jansson & Müller, 2003). Accordingly, most second home owners live close to their property. Even in an international context, long-distance second home ownership is still the exception (Hoggart & Buller, 1995). Space–time distance forms an obstacle for second home ownership that favours second home ownership within the weekend zone of the owners’ primary residences and, thus, most second homes may be labelled ‘weekend homes. These weekend homes can be visited frequently and also for short periods (Table ...