![]()

1 Mass Tourism, Diversification and

Sustainability in Southern Europe's

Coastal Regions

Bill Bramwell

Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield S1 1WB, UK

Introduction

International mass tourism came of age in the coastal areas and islands of Mediterranean Europe in the decades after the late 1950s. The transformation of Europe's Mediterranean into a tourism belt was the latest in a series of roles that the region has played. Two thousand years ago it had been the cradle of the Greek and Roman empires, gaining supplementary income as a result of military expansion. Subsequently, the Venetian, Turkish and Spanish empires came to exercise their trading and political power. But by the Renaissance period, commercial hegemony had substantially shifted to north-west Europe where wealth was increasingly vested in industrial production and trade. Europe's subsequent industrial revolution was also focused to the north and largely by-passed the Mediterranean, where most of its regions had a largely subordinate role in a wider division of labour, leading to peripherality, dependency, poverty and rural depopulation (Dunford, 1997: 127). From the industrial revolution until the 1960s the economy of Europe's Mediterranean substantially lagged behind that of northern Europe. Paradoxically, it was the population of industrialised northern Europe that fuelled one of the engines for southern Europe's ‘renaissance’ from the 1960s – through tourist flows from north to south. From that period onwards, tourism activities – alongside commercialised agriculture, industrial development and expanded urban services – have contributed to southern Europe's ‘rebirth’ (King & Donati, 1999: 134–9).

From the late 1950s onwards many coastal areas of first Spain and Italy, followed by Greece, Malta, Cyprus and former Yugoslavia, began attracting unprecedented numbers of tourists from northern Europe. The holidays offered in this ‘pleasure periphery’ were largely socially constructed as sun and sea experiences, with better prospects of sun and warmth than in the north (Williams, 1997: 214). It became possible for large numbers of people from diverse social groups to be involved because of the rising incomes of post-war prosperity, longer and paid holidays, and because of innovations in transport technology, notably the commercial jet airliner. Another key element was the tourism industry's large-scale replication of standardised holiday packages combining accommodation and transport, marketed by new types of tour operators. The accommodation and other commercial facilities necessary for these new developments were sometimes financed by capital originating from external, ‘core’ metropolitan regions, but also often from small-scale investments within the destination areas (Ioannides, 2001a: 117; Sprengel, 1999; Yarcan & Ertuna, 2002: 169, 180). The large volume of package holidays, aggressively sold, created the scale economies that made these holidays a widely affordable form of mass consumption. In addition, many visitors, including increasingly significant numbers of domestic tourists, holidayed independently, without tour operator involvement (Jenner & Smith, 1993: 51–7; Williams, 2001: 169).

Overall, therefore, post-war southern Europe has seen major growth in tourism as an economic activity, which has contributed to wider processes of globalisation. But tourism's specific character and its impacts vary considerably between southern Europe's many coastal regions and resorts. Where the industry has developed it has often been accompanied by economic, sociocultural and environmental changes. These have been more evident because the countries of southern Europe had been slow to industrialise and modernise, although many of them – notably Italy, Spain, Greece, Cyprus and Malta – experienced a period of dynamic economic growth and improved wealth between the 1960s and 1980s (Dunford, 1997: 127, 134, 150; King & Donati, 1999: 137). Tourism's impacts were also prominent because large tracts of the Mediterranean littoral had previously been comparatively undeveloped, were characterised by fairly traditional societies, and they often also had fragile coastal environments (Sapelli, 1995: 13). However, tourism activity has been only one of many significant influences working to transform southern Europe in the post-war period, including economic change from intensified and commercialised agriculture in irrigated areas, the development of various infrastructural projects, and an expanding urban economy (Dunford, 1997: 150–52).

While residents in these regions have often responded quite positively to tourism, their reactions have also varied from place to place (Barke, 1999; Haralambopoulos & Pizam, 1993; Richez, 1996; Tsartas, 1992). Concerns about the industry's adverse environmental and sociocultural impacts have grown in recent years in southern Europe, but these post-materialist sensitivities have developed more slowly here than in more affluent countries. The views of policy-makers, the industry and NGOs in southern Europe about tourism's costs and benefits are increasingly framed within discourses on sustainable development (Kousis & Eder, 2001: 17). While the debates sometimes focus on environmental and sociocultural issues and on inequitable outcomes, fears about the economic vitality of mass tourism are especially prominent. Several threats to its economic strength are now identified, including ageing infrastructure, environmental deterioration, changes in tourists’ expectations of environmental standards, and growing competition from an ever-expanding choice of holiday destinations both within the region and across the world.

Over the past 20 years anxiety in southern Europe's coastlands about mass tourism's future economic health has encouraged policy-makers to advocate greater product diversification. One policy response has involved developing new, large-scale products, such as golf courses, marinas, casinos and exhibition and conference centres, with these often intended to attract high spend visitors. While these developments may be aimed at ‘exclusive’, ‘up-market’ audiences, they have many mass tourism features as they are large facilities that attract substantial numbers of users. A second policy response to diversification has involved developing ‘alternative’ tourism products that, at least initially, may be provided on a small scale and may draw on unique features, such as a destination's history, culture or ecology. Typical products of this type include hiking trails in natural areas, agro-tourism facilities, and improved interpretation at small historic sites and museums. ‘Alternative’ products are often considered better adapted to the changing tastes of consumers, who, it is suggested, are increasingly looking for more specialist and customised holiday experiences. But a rather different set of policies has emerged because of the concern about mass tourism, with these intended to update and improve the environmental performance of the existing infrastructure and products. It is thought that many holiday-makers no longer accept poor environmental standards, and thus environmental quality has to be improved. The environmental upgrading of existing products can be achieved using enhancement schemes in major resorts, tougher land-use planning controls, improvements in water quality and beach cleaning, and initiatives to reduce energy use and recycle waste in the accommodation sector. This upgrading of environmental performance has often been coupled with higher standards of provision generally, with air conditioning, en suite facilities and leisure complexes attached to tourist accommodation.

To date, surprisingly few books have been published that focus on the development and planning of coastal mass tourism, and there has been only a limited critical assessment of the strategies of product diversification and environmental enhancement used in coastal regions. This book tackles these topics in the specific context of Europe's Mediterranean. Consideration is given to the policy approaches and planning techniques being used, the intentions and underlying assumptions behind their use, and the types of products that result. Particular attention is paid to the successes and failures of these strategies and techniques in relation to the objectives of achieving sustainable development. Do the policies put forward, and their related products and developments, encourage sustainable outcomes? These themes are considered in case studies from Spain, Greece, Malta, Croatia, Turkey and from both north and south Cyprus. The examples that are examined illustrate how the issues and outcomes depend very much on the contingencies of each case, a point that is not always fully acknowledged in the tourism literature. But, while the book draws on the European Mediterranean experience, there are implications for other coastal areas in the world, such as Bulgaria's Black Sea coast, the beach resorts of West Malaysia, Australia's Gold Coast, and for other parts of the Mediterranean's coasts beyond southern Europe.

This chapter and the next review key themes from the book's subsequent contributions, while also drawing on other relevant studies. The discussion in this chapter focuses on the development of mass, ‘alternative’ and other tourism forms in southern Europe's coastal regions, as well as their potential disadvantages and advantages for sustainability. Despite its very many potential advantages, it warns against assuming that small-scale ‘alternative’ tourism is inevitably more appropriate for sustainable development than mass tourism. The second chapter considers the contexts behind the initiation of public policies for coastal mass tourism and sustainable development in southern Europe. This includes policies developed by the European Union and by national and local government.

Coastal Mass Tourism in Southern Europe

The geographic context

A regional view of coastal tourism is adopted here. The regions under consideration all border the Mediterranean Sea but they usually also include quite extensive hinterlands within which socioeconomic activities are strongly influenced by their relations with the seaboard and its coastal tourism industry. A regional view is supported by the Blue Plan – the plan for environmental improvement of the Mediterranean Basin that was sponsored by the United Nations Environment Programme. This plan recognises that in the Mediterranean the ‘coastal zones might vary in territorial depth from one area to another, depending on the problems to be considered and the nature of the disciplines involved’ (Grenon & Batisse, 1989: 16).

Each European Mediterranean region reflects distinctive, multilayered interactions between its climate, environments and landscapes, historical and cultural legacies and contemporary socioeconomic geographies. While each of these regions is unique, there are some characteristics that are quite widely shared (King et al., 2001). For example, while the climate can vary from place to place, in essence it is characterised by the summer heat and drought. This climate has largely been responsible for the distinctive mixes of vegetation and crops, such as the olive, vine, fig and Aleppo pine; and the climate together with the terrain have helped to shape the pastoralism and agriculture in each region. The coastal strips of many Mediterranean regions are backed by hilly or mountainous landscapes. There is intense debate and disagreement among academics about the cultural characteristics of Mediterranean Europe, with some anthropologists suggesting that it has been characterised by the values of honour and shame, together with strong ‘traditional’ kinship and gender roles, and that these features retain an influence on behaviour (Horden & Purcell, 2000: 485–523; Sapelli, 1995). Other commentators point to ‘a rapidly changing reality’, with ‘trends towards a more individualistic and consumer orientated society’ (Hudson & Lewis, 1985: 1, 15). In southern Europe there has also been a long tradition of urban life, with the many port cities around the Mediterranean testifying to this tradition and to the significance of this sea for trade routes. Since the 1960s many of southern Europe's coastal regions have undergone substantial change due to selective development and modernisation. Mass tourism has been just one important economic and sociocultural influence encouraging these changes.

The growth in international tourism

While there is some discussion of domestic tourism in this chapter, its focus is on international tourism around Europe's Mediterranean shores, starting with a brief history of its development. In the era of élite international tourism before the First World War the French and Italian Rivieras were winter playgrounds for a wealthy upper middle class from northern Europe. From the late 1950s, international tourism gained a mass character based on widening social access and the attractions of warm seas, secure summer sunshine, and often stereotypes or myths about the ‘Mediterranean’ (Minca, 1998). The industry has spread through a succession of poles of high growth, and its present distribution is highly spatially uneven between and within countries, regions and localities. In the 1950s it grew markedly in Spain, the early market leader, and on the Italian Adriatic. By the early 1970s tourism was expanding in parts of former Yugoslavia, the Greekislands, Malta and Cyprus, and by the late 1970s and 1980s it had reached Turkey (Williams, 1998: 51; 2001: 161). The rapid growth of the 1960s and 1970s meant the southern European littoral was quickly established among the world's premier holiday destinations (Jenner & Smith, 1993; Montanari, 1995: 43). Looking ahead, tourism in many parts of Europe's Mediterranean is likely to continue to grow, but this region's share of the global market is declining because there is increasing competition from newer tourist destinations, and because it is distant from the fastest growing tourist markets, notably Asia with its emerging new economies and rapid population growth.

Figure 1 The Mediterranean countries of southern Europe and Turkey

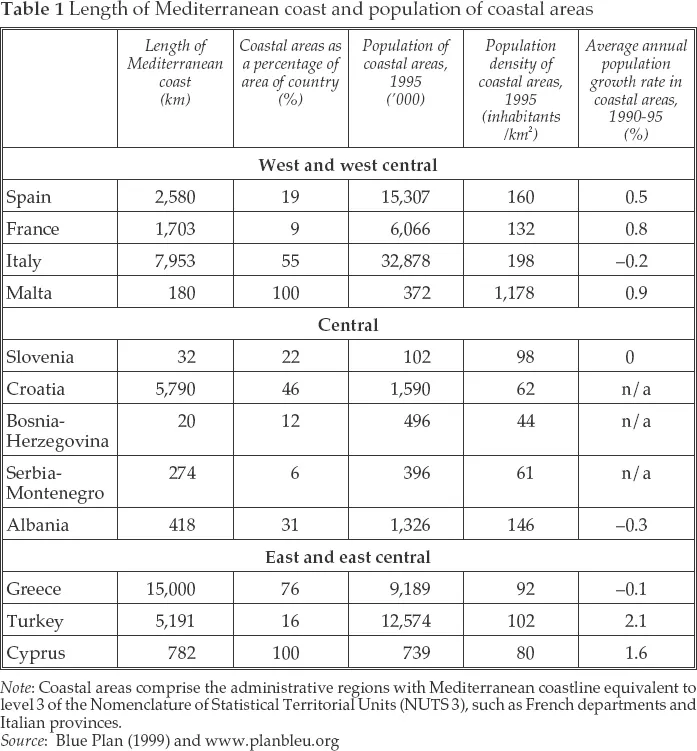

Figure 1 shows the 12 countries of southern Europe that include a Mediterranean coastline and thus are considered in this book. Within each country the length of this littoral varies from only 20 km in Bosnia-Herzegovina and 32 km in Slovenia to the extensive coasts of Greece (15,000 km), Italy (7953 km) and Croatia (5790 km) (Table 1). The figures for Greece and Croatia are boosted by their many islands. While Portugal is in southern Europe, it is not examined here as it fringes the Atlantic Ocean, but Turkey's regions bordering the Mediterranean are included. Turkey acts as a ‘bridge’ between East and West and has affinities with Europe as well as Asia; it is striving to join the European Union, and its Mediterranean tourism also depends substantially on visitors from northern Europe (Sapelli, 1995). Table 1 shows that among the 12 countries, those receiving most international tourist arrivals in 2000 were France (75 million), Spain (48 million), Italy (41 million), Greece (12 million) and Turkey (9 million). Unfortunately, these figures include tourists staying elsewhere rather than near the Mediterranean. For example, the proportion in France staying in Mediterranean coastal regions is modest, influenced by these regions comprising less than 10% of the country's land area (Blue Plan, 1999; King et al., 2001). Coastal mass tourism is a particularly prominent influence on the small island states of Cyprus and Malta: in Cyprus there are 3.54 international tourists per head of population and in Malta this ratio is 3.10 (Table 2).

The growth in numbers of international tourists visiting southern Europe's coasts has not been continuous. The ups and downs of the economic cycle and military conflicts such as the Gulf War have been important for all destinations. And in some of the 12 countries domestic or regional political problems have halted international tourism growth altogether or for long periods. For instance, military events and political instability mean that Albania largely remains outside of the international tourism system. In the case of the former Yugoslavia, in 1988 it attracted over nine million international tourists, over a million more than neighbouring Greece, but conflict and political disintegration subsequently devastated this industry (Jordan, 2000: 525). However, by 2000 tourist arrivals in Croatia and Slovenia had recovered to six million and one million respectively. Chapters 15 (by Scott) and 7 (by Sadler) describe how the industry's growth in north Cyprus has been limited because this territory lacks international political recognition following the intervention of Turkish troops in 1974. This l...