![]()

Chapter 1

An Introduction to Educational Tourism

Introduction

The growth of both education and tourism as industries in recent decades has led to growing recognition of these industries from both an economic and social perspective. As Roppolo (1996: 191) notes, ‘as countries become more interdependent, their success, growth and economic prosperity will largely depend on the ability of two industries – education and tourism – to create the avenues necessary to support international exchange and learning’. The changes in the tourism industry over the last two decades coupled with the changes in education have seen the convergence of these two industries with education facilitating mobility and learning becoming an important part of the tourist experience. Smith and Jenner note that educational tourism has generated little excitement to date from the tourist industry and this is reflected in the gathering of research and data. They note that ‘very little research has been done because this segment is not seen as warranting it, yet because little research has been done, the industry is unaware of the true size of the segment’ (Smith & Jenner, 1997a: 60). Roppolo (1996) agrees and notes that there are many areas yet to be examined empirically concerning the links between education and tourism.

This chapter begins by exploring relationships between education, tourism and educational tourism, first with a section to assist the reader in understanding tourism (definitions of tourism and the growth of this sector) and education (definitions of education and learning and the growth of education and lifelong learning). The chapter then discusses educational forms of tourism by providing a brief history and an outline of how educational tourism may be conceptualised or understood. The chapter argues that a systems and segmentation approach to understanding educational tourism is useful and concludes that, although educational tourism is a broad and complicated field with limited past research, the importance of this area of tourism is likely to grow due to trends in both the tourism and education sectors.

Understanding Tourism

Tourism is one of the fastest growing industries taking place in both developed and developing countries worldwide. The growth of tourism has been fuelled by the growth in leisure time combined with an increase in discretionary income and a desire to escape and engage in holidays both domestically and internationally. Definitions of tourism vary with respect to whether the definition is from a supply-side (industry) or demand-side (consumer) perspective. As Smith (1988: 181) has noted, ‘there are many different legitimate definitions of tourism that serve many different, legitimate needs’. Moreover, many of the tourism definitions vary due to the organisation or individual trying to define tourism and to their motives. However, there are commonalities between many of the definitions.

Former tourism definitions stated that a minimum of a 24-hour stay was required to be considered a tourist. However, this has been modified to an overnight stay, which, according to Weaver and Oppermann (2000: 28), ‘is a significant improvement over the former criterion of a 24-hour stay, which proved to be both arbitrary and extremely difficult to apply’. If a person’s trip does not incorporate at least one overnight stay, then the term excursionist is applied (Weaver & Oppermann, 2000). This definition can be applied to both international and domestic travellers. For example, international stayovers (or tourists) are those that stay in a destination outside of their usual country of residence for at least one night, while international excursionists (or same-day visitors) stay in an international location without staying overnight. Furthermore, a domestic stayover (or tourist) is someone who stays overnight in a destination that is within their own country of residence but outside of their usual home environment (usually specified by a distance of some kind). Domestic excursionists (or same-day visitors) undertake a similar trip but do not stay overnight.

Smith (1988) believes that it is difficult to determine the precise magnitude of the tourism industry due to the absence of an accepted operational definition of tourism. Nevertheless, the tourism industry has been defined as an industry that ‘encompasses all activities which supply, directly or indirectly, goods and services purchased by tourists’ (Hollander, Threlfall & Tucker, 1982: 2). Hall (1995: 9) believes that the following three factors emerge when examining the myriad definitions concerning the tourism industry:

• the tourism industry is regarded as essentially a service industry;

• the inclusion of business, pleasure, and leisure activities emphasises ‘the nature of the goods a traveller requires to make the trip more successful, easier, or enjoyable’ (Smith, 1988: 183); and

• the notion of a ‘home environment’, refers to the arbitrary delineation of a distance threshold or period of overnight stay.

However, McIntosh et al. (1995: 10) take a more systems-based approach when defining tourism as ‘the sum of phenomena and relationships arising from the interaction of tourists, business suppliers, host governments, and host communities in the process of attracting and hosting these tourists and other visitors’. This definition includes the potential impacts that tourists may have upon the host community, and also includes ‘other’ visitors such as students.

The above discussion illustrates that there are many different components to defining tourism, which range from tourists themselves, the tourism industry and even the host community or destination. A number of authors view tourism therefore as an integrated system of components (Gunn, 1988; Leiper, 1989; Mathieson & Wall, 1982; Mill & Morrison, 1985; Murphy, 1985; Pearce, 1989), which generally have a number of interrelated factors:

• a demand side consisting of the tourist market and their characteristics (motives, perceptions, socio-demographics);

• a supply side consisting of the tourism industry (transport, attractions, services, information, which combine to form a tourist destination area);

• a tourism impact side whereby the consequences of tourism can have either direct or indirect positive and negative impacts upon a destination area and the tourists themselves;

• an origin–destination approach which illustrates the interdependence of generating and receiving destinations and transit destinations (en route) and their demand, supply and impacts.

According to the World Tourism Organization (WTO, 1999) tourism is predicted to increase with future tourist arrivals growing to 1.6 billion by the year 2020 at an average growth rate of 4.3%. Despite the effect of external factors such as the Asian Economic Crisis in the late 1990s and the September 11 incident in 2001, tourism growth appears to be assured. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC, 2001) tourism currently generates 6% of global Gross National Product and employs one in 15 workers worldwide. It is predicted that by 2011 it will directly and indirectly support one in 11.2 workers and contribute 9% of Gross National Product worldwide (WTTC, 2001).

The growth of tourism has spread geographically with the market share of tourist arrivals reducing in Europe and increasing in the Asia-Pacific area, which has the fastest growth rate of world tourist arrivals. There has also been a growth in tourism to developing countries with their share of tourist arrivals and expenditure increasing especially in destinations such as Eastern Europe, South America, the Middle East and Africa. Tourists are now more than ever travelling further in search of new and unusual experiences.

However, the growth of tourism on a worldwide scale, coupled with the search for new destinations and experiences, has added to the questioning of tourism impacts and calls for more sustainable or ‘alternative’ types of tourism. The problems associated with mass tourism and the ability of tourism to transform destinations and impact negatively upon host communities is well recognised (Fennell, 1999) and there is a move toward more ‘soft’, ‘sustainable’ or ‘alternative’ forms of tourism. Since the 1980s the tourist marketplace has become increasingly specialised and segmented resulting in the growth of niche markets such as rural tourism, ecotourism, adventure tourism and cultural heritage tourism. Furthermore, a number of educational and learning experiences within tourism appear to be increasing (CTC, 2001), while travel and tourism experiences specifically for study or learning also appear to be increasing (Roppolo, 1996), illustrating the potential for educational forms of tourism.

Understanding Education and Learning

Education has been defined as ‘the organized, systematic effort to foster learning, to establish the conditions, and to provide the activities through which learning can occur’ (Smith, 1982: 37). The key word ‘learning’ indicates some form of process. As Kulich (1987) states, learning is a natural process which occurs throughout one’s life and is quite often incidental, whereas education is a more conscious, planned and systematic process dependent upon learning objectives and learning strategies. Education therefore can be considered as consisting of formal learning through attending classes, language schools, and so on, or participating in further, higher or work-based education.

Nevertheless, despite the presentation of definitions, authors such as Kidd (1973) and Smith (1982) believe that there is no precise definition of learning, because it can refer to a product (where the outcome is important), a process (which occurs during learning) and a function (the actual steps to achieve learning). Therefore, from these observations it becomes clear that educational tourism may be viewed in a similar way, as a product, process and function. In other words as a product the emphasis is on the outcome of the learning experience (such as a university degree for international university students). While viewing it as a process or a function the focus is on the means to an end (Kalinowski & Weiler, 1992). For instance, if learning is itself defined as an end, then the experience may be focused upon mastering or improving knowledge of what is already known about something (such as a trip to a marine biology station to learn about marine biology). Furthermore, if learning is derived as a means to an end, then, according to Kalinowski and Weiler (1992), the focus is to extend or apply previous study; for example, travelling to an ancient monument after studying the monument. Thus from these definitions it can be seen that travel for educational purposes can be a diverse and complicated area of study.

There appears to be a contemporary transition from an industrial to a knowledge-based or learning economy and society with an increasing emphasis on extending learning beyond initial schooling (OECD, 2001). The reasons behind a drive to extend learning beyond schooling is so that individuals, communities and countries are able to better adjust themselves to current and future changes, and are more likely to contribute to society through increased innovation, business development and economic growth. Another rationale behind the drive for education and lifelong learning is to provide a more inclusive and fair society by making education more accessible, particularly to less privileged members of society (DFES, 2001). Generally speaking education and lifelong learning are said to encompass ‘all learning activity undertaken throughout life, with the aim of improving knowledge, skills and competence, within a personal, civic, social and/or employment-related perspective’ (European Union, 2001).

Since the 2001 general election the British government has created the Department for Education and Skills and a State Minister for Lifelong Learning and Higher Education. The aims of the Department for Education and Skills (2001: 5) are to help build a competitive economy and inclusive society by:

• creating opportunities for everyone to develop their learning;

• releasing potential in people to make the most of themselves; and

• achieving excellence in standards of education and levels of skills.

Their objectives to achieve their aims are to:

• give children an excellent start in education so that they have a better foundation for future learning;

• enable all young people to develop and to equip themselves with the skills, knowledge and personal qualities needed for life and work; and

• encourage and enable adults to learn, improve their skills and enrich their lives.

Similarly, the Enterprise and Lifelong Learning Department (ELLD) of the Scottish Executive is responsible for economic and industrial development, tourism, further and higher education, student support, and skills and lifelong learning in Scotland. ELLD promotes lifelong learning through policy development and funding for further adult education and higher education in Scotland.

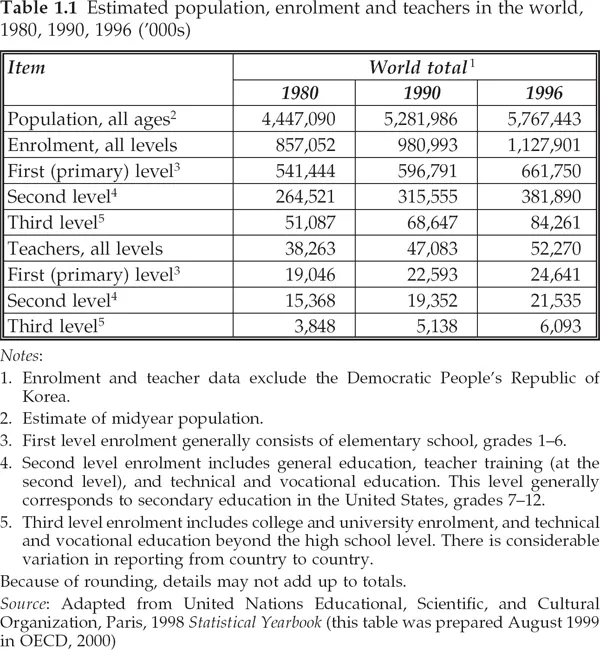

The policies of Western governments toward lifelong learning, as seen above, combined with a growth in economic development and prosperity, has seen a rise in the provision of post-secondary education. Coupled with this growth has been an increase in provision of colleges and institutions to cater for the demand for educational qualifications (see Table 1.1). The higher education market (or third level enrolment) is also expanding rapidly as income levels rise in the developed world, thus allowing for greater expenditure on education by parents. As Table 1.2 notes, the USA had 14.4 million students in higher education followed by Russia with 4.5 million and Japan with 2.8 million students enrolled in higher education (Smith & Jenner, 1997a). UNESCO (1995 in Smith & Jenner, 1997a: 64) estimates suggest that in 1980 a total of 30% of young people in the developed world were in higher education, rising to 40% in 1991 and predicted to be 50% by early 2000. This would mean a total of 79 million enrolled in higher education in the year 2000 rising to 97 million in 2015 and 100 million in 2025.

Furthermore, Roppolo (1996) notes that educational institutions will need to incorporate international experiences into their curriculum in light of the growing interdependence of countries, providing benefits to both students and the tourism industry. In the United States foreign students enrolled in higher education institutions has risen from 311,000 in 1980–81 to 481,000 in 1997–98 (Institute of International Education, 1998). This is partly due to economic prosperity but also the relaxation in border and visa controls and social changes in generating countries allowing the development of student exchange programmes. In the United States from the 481,000 foreign students a total of 57.9% in 1997–98 were from Asia, followed by 14.9% from Europe and 10.7% from Latin America. The biggest increase in market share from 1980 to 1998 in the United States appears to be from Asia and Europe, which has grown from 30.3% and 8.1% to comprise 57.9% and 14.9% of the market respectively (Institute of International Education, 1998). This rapid increase in foreign students in higher education is not limited to North America. In Australia the number of overseas students enrolled in higher education institutions has risen by 51.5% since 1994 and over 30% per annum over the period 1994 to 1996 (DEETYA, 1998 in Musca & Shanka, 1998). These statistics illustrate the economic significance of education and the growth in international students and offshore education.

Table 1.2 Number in higher education in selected countries, 1993 (’000s)

| Country | Higher/University pupils |

| Germany | 1,875 |

| France | 2,075 |

| UK | 1,528 |

| Spain | 1,371 |

| Italy | 1,682 |

| Netherlands | 507 |

| Russia | 4,587 |

| Poland | 694 |

| Czech Republic | 129 |

| USA | 14,473 |

| Canada | 2,01... |