eBook - ePub

Trends in European Tourism Planning and Organisation

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Trends in European Tourism Planning and Organisation

About this book

Written by leading international tourism researchers, this book examines the key trends in European tourism planning and organisation. It introduces a theoretical framework to tourism planning and organisation using a procedural and structural approach. Despite having a European focus, it is globally relevant as many lessons from Europe can be applied to international tourism development. The book identifies and discusses six key themes in the context of European tourism planning and organisation: territory, actors and structures, economics, policy, methods and techniques and vision. It also identifies leading and emerging practices and offers a new vision for European tourism planning.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Trends in European Tourism Planning and Organisation by Carlos Costa,Emese Panyik,Dimitrios Buhalis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Hospitality, Travel & Tourism Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Towards a Conceptual Framework: An Introduction

Carlos Costa, Emese Panyik and Dimitrios Buhalis

Positioning Tourism in the Global World Economy

The world has changed dramatically over the last few decades. During the 1990s there was an emerging dialogue arguing that globalisation would change the face of the world’s economy, and much was written about the benefits and shortcomings of globalisation. In the first quarter of the 21st century most of the rhetoric associated with this discussion materialised quickly and dramatically in many ways. The world has undoubtedly become borderless; competition at a global scale has come to stay. The emerging reality in the first decades of the 21st century is dominated by a world where people travel easily from one destination to another, where environmental problems created in one place impact on other parts of the world, and where information technology, particularly social networks, brings people together, turning the world effectively into a common village where citizens communicate with each other without any kind of barrier.

At the same time, globalisation has brought about a restructuring of the political space, challenging the traditional physical and administrative organ-isation of locations. Supranational and subnational formations are mushrooming around the world, which have become equally as or even more important than nation states in global negotiations (Ohmae, 1995). Paradoxically, globalisation has not only triggered this restructuring, but it has also reinforced it through processes of fragmentation, notably regionalisation and localisation. As Gamble et al. (1996: 3) put it:

A new stage in the development of the world economic and political system has commenced, a new kind of world order, which is characterised both by unprecedented unity and unprecedented fragmentation.

The shift of focus from the autonomous nation states towards the global market economy implies that the development of countries ultimately lies in their ability to adapt to rapidly changing global economic conditions. Consequently, contemporary geopolitical trends are intimately tied to the global economic architecture.

On top of this, the world’s economy has not only become interlocked but also multipolar. Europe, America and China have become the leaders of the world economy, and the currencies of these regions have turned out to be the blood of the world’s commercial transactions. Competition among these economic areas has become fierce, and the rationale supporting chaos theory has come to stay: whenever an economic crisis emerges within one of these blocks, the other regions – and the other countries in the world – feel the consequences.

The economic evolution of the world is sparking new but contrasting approaches. Far from the scenario of economic expansion of the post-World War II period, when governments acted as leaders and boosters of the economic expansion, there has been a shift towards the market as the guiding principle of government activity. Most nations are reducing their operations in order to release resources, to strengthen the private sector, to increase organisations’ efficiency and effectiveness and to reduce public debt. The challenges faced by the welfare state in the early 1980s showed that all-round national welfare systems are untenable in the long run, even in advanced capitalist nations. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in Europe, where the diversity of cultures and the legacy of long histories and strong human rights policies have shaped the evolutionary path of planning and welfare systems. Today, the aging of populations is more advanced and the social welfare net is more extended in Europe than in most other parts of the world. As a result of this, the world is increasingly witnessing a retreat from welfare state activities and the market provision of formerly public goods and services (Larner, 2000).

While the bureaucratic structures of state intervention are being challenged, governments are also becoming aware that markets ought to be regulated properly. The problems created by, and within, the financial markets at the beginning of the 21st century have fuelled that need.

Considering the recent global economic highlights, the OECD’s global outlook on the world economy suggests that cracks are forming in the conglomerate of Western world economies as Europe and the United States drift apart. While the United States stays on the track of economic recovery, European budget cuts depress demand in the region, contributing to a prolonged recession (Parussini & Hannon, 2012). The OECD has urged the European Union’s (EU’s) leading authorities to introduce measures aimed at boosting the bloc’s competitiveness, particularly that of the service sector. This directs the spotlight onto tourism, which has proved capable of growth despite the restraining conditions.

The Challenges of European Tourism

In an era characterised by stalled global economic recovery, tourism upholds a remarkable upward trend. International tourist arrivals grew by over 4% in 2011 to reach 980 million. According to the estimation of the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), international tourist arrivals are on track to reach the 1 billion milestone by the end of 2012. As UNWTO Secretary-General, Taleb Rifai, said:

For a sector directly responsible for 5% of the world’s GDP, 6% of total exports and employing one out of every 12 people in advanced and emerging economies alike, these results are encouraging, coming as they do at a time in which we urgently need levers to stimulate growth and job creation. (UNWTO, 2012)

Europe in particular, with the greatest diversity and density of tourist attractions among the continents, is the most visited tourist destination in the world. It accounts for 51% of international tourist arrivals and 44% of international tourist receipts (UNWTO, 2011, 2012). Europe is also one of the main tourism-generating markets in the world, although European tourism is largely domestic. Approximately 90% of European outbound tourism was recorded in the EU (EC, 2010). Despite persistent economic uncertainty, inter-national tourist arrivals in Europe surpassed the half-billion mark in 2011 (503 million: UNWTO, 2012), and, long-term forecasts suggest that the old continent is likely to retain its leading position.

Tourism is also a cross-cutting sector and an essential economic activity in the EU, representing the third largest socio-economic activity after the trade and distribution and construction sectors. It generates over 5% of EU GDP, employing approximately 5.2% of the total workforce (EC, 2010). During recent decades, the tourism policy of many European countries has gone through structural change and innovation, showing a continuous concern for improving its management by way of adapting structures, investing in new product development and reinforcing public–private partnerships (WTO, 2003). Particular attention was given to the role that the EU could play in tourism development and the leverage it could provide to the member states and the Community as a whole. The 1995 Green Paper on Tourism was the first EC communication dedicated entirely to the role of the EU in assisting tourism, with the aim of stimulating thoughts on deepening its future involvement. Indeed, the potential of tourism in job creation has been recognised, due to the fact that the annual growth rate of people employed in the HORECA (Hotels, Restaurants and Cafes) sector in the EU has almost always been above the growth rate of total employment (EC, 2006). Hence, as an area of mutual interest for politics and business, employment generation has attracted growing attention. Notably, the ‘Tourism and Employment’ process launched in 1997 has been themed around strategic areas, including information technology, training, quality development, environmental protection and sustainability.

New Perspectives in Light of the Lisbon Treaty

Until very recently, there has been no success in exploiting the potential of a coherent EU tourism policy, due to the lack of a direct legal base for Community measures on tourism. Decision making was hampered by restrictive conditions, in that any act of the Council of Ministers needed unanimity among all member states. The failure to adopt the first multiannual programme, ‘Philoxenia’, to assist European tourism in 1996 was one example of such a procedural obstacle.

Two decades ago, Johnson and Thomas (1992) envisioned that the EU had developed a rudimentary but nevertheless evolutionary tourism policy that was capable of expansion into an effective and timely action programme. The inclusion of tourism in the areas of the EU’s supporting competence by the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 may lend support to this claim. As laid down by Article 195, the EU can promote the competitiveness of undertakings in this sector, encourage cooperation between the member states in the area and develop an integrated approach to tourism.

In order for European tourism to evolve in the face of the current economic recession, change is required at all levels. This may provide the EU with a historic opportunity for active involvement by means of supranational coordination. The new action framework put forward by the Commission set out ‘sustainable competitiveness’ as the main goal of European tourism policy, which calls for a new approach to tourism planning and organisation at the European level.

Towards a New Conceptual Framework

The existing research with a supply-side focus on European tourism is fairly limited and mostly outdated (Bramham et al., 1993; Davidson, 1998; Hall et al., 2006; Pompl & Lavery, 1993; Williams & Shaw, 1998), lacking a systematic analysis of mainstream European planning and organisation trends through the key underlying concepts. Planners often tend to undervalue the importance of the administrative component of planning and focus rather on the procedural component, although in fact both are equally important for the improvement of the efficiency and effectiveness of the planning activity. Furthermore, the links between territory and actors in the planning process are often neglected. Bearing this in mind, the present textbook aims to fill the gaps mentioned above and offers a new, holistic perspective on European tourism planning.

New linkages between development and governance: A procedural approach

The planning and organisation of the tourism sector have evolved significantly over the past decades (Costa, 2001). At the beginning of the 20th century, planning was undertaken under the sphere of influence of urban and regional planning, and was mainly oriented towards the physical organ-isation of the territory (the classic planning paradigm). At that time, most of the problems in tourism were concerned with the location and quality of the infrastructure and equipment of emerging hotels and small facilities, which were solved within town planning. ‘Tourism planning’ was then viewed as a minor activity, without its own body of knowledge.

As the classic planning paradigm faded out and the rational planning paradigm emerged, physical planning and the organisation of tourism systems began to be approached in a broader way, encompassing variables related to demographic trends, mathematical models and cybernics. The importance of the social sciences also increased, as the Chicago School developed and brought into practice a new generation of ideas and models. During this phase, planning was seen as a technocratic, rational and scientific approach, because it was believed that it had the capacity to create scientific and ‘right’ decisions for the communities.

Since the late 1970s profound changes have started to emerge worldwide. First, most of the physical problems related with the (previously) poor quality of the infrastructure and equipment were solved. Secondly, market-led orientations and neoliberalism began to emerge. Moreover, the world’s population became increasingly better educated and willing to participate in decision-making processes. In addition, governments had to diminish their capacity in to intervene in society, because many public organisations had become too bureaucratic, inefficient, ineffective and poorly regarded.

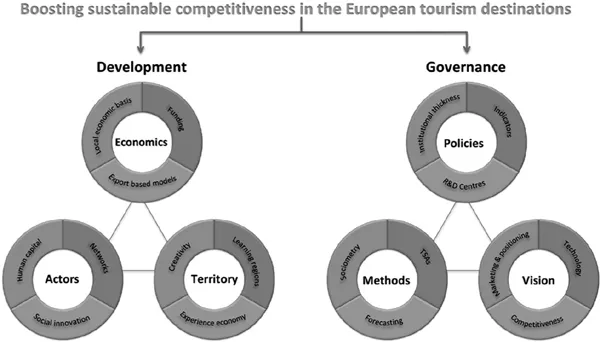

A call for new planning and organisational approaches has recently started to emerge (Costa, 2001). In the first quarter of the 21st century it is believed that the evolution of successful planning and organisation in the tourism sector should take account of the development of the territory and its governance (Figure 1.1). The development of tourism systems should be founded on an efficient and effective economy, linked to an interconnected local economic basis that orients its production towards the export of their products and services, because, as a result of this, they will gain competitive advantages in relation to other destinations. Due to increasing worldwide competition and easier delocalisation of investment, destinations should also look for local investment in addition to international sources of funding in order to ensure forms of sustained economic development.

The new economics of tourism destinations should also be viewed with very close ties to the actors and to the territory. Human capital is becoming the cornerstone of successful destinations. The emphasis on human resourceshas to be seen through the creation of modern and effective public participation which leads destinations towards social innovation. Networks play a critical role in achieving this, because they are among the most effective ways of linking together local stakeholders. In the new economy the territory gains even more importance not only because it is critical for the establishment of the price of products and services, but also because people choose destinations that offer them quality of life. The need to develop creative regions capable of providing new experiences and also to create destinations that learn how to achieve competitive advantages has come to the top of the planners’ agenda.

Figure 1.1 New linkages between development and governance: A procedural approach

The success of tourism destinations depends increasingly not only on the way they succeed/perform from an economic point of view but also on the way they are governed. Beside this, economic efficiency and effectiveness depend on how destinations create organisational structures capable of man-aging and leading them into the future.

In accordance with this, the call for the introduction of effective tourism policies will return as a matter of priority to the planners’ agenda. In a modern vision, policies have to be designed through the direct involvement of all stakeholders, because they are designed for them and also because they may make them knowledgeable. Since most of the tourism organisations are small and do not have an agenda for innovation, policies ought to be designed in close association with research centres. Also, they should be supported with clear management indicators, so they can be scrutinised and so that the public will better understand and support them.

While it is no longer possible to design policies under the principles of the technocratic rational paradigm, it is also increasingly believed that how public resources are spent must be supported by evidence. Therefore, policies should be justified by clear forecasting methods, by how they will benefit a networked society, and by how the economy will benefit from them (TSAs). Besides, policies must be set up by clearly defining the targets they will reach and how they will introduce more competitiveness into the systems. The need for a better vision for tourism destinations also includes the development of modern information technolo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acronyms

- Contributors

- 1 Towards a Conceptual Framework: An Introduction

- Part 1: Territory

- Part 2: Actors and Structures

- Part 3: Economics

- Part 4: Policy

- Part 5: Methods and Techniques

- Part 6: Vision