eBook - ePub

The Language Difference

Language and Development in the Greater Mekong Sub-Region

Paulin G. Djité

This is a test

Share book

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Language Difference

Language and Development in the Greater Mekong Sub-Region

Paulin G. Djité

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Language is a sensitive issue in the developing world, because language choice and behaviour are integral to the social, economic and political stability of multicultural societies. To what extent does this argument hold? Does language make a difference when it comes to development, and is there a perceptible difference in development between countries that is attributable to their choice of language? This book sets out to answer these questions by investigating how language has been and is being used in four countries of the Greater Mekong Sub-region (i.e. Cambodia, the Lao PDR, Myanmar and Viet Nam), especially in the critical areas of education, health, the economy and governance.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Language Difference an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Language Difference by Paulin G. Djité in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Sociolinguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Language and Development in the Greater Mekong Sub-Region

Introduction

At first glance, there is a language difference between African countries and the country of the Greater Mekong Sub-Region (GMS). In contrast with the former, language issues in Cambodia, the Lao PDR, Myanmar and Viet Nam seem to have been successfully resolved via the adoption of a national language, suggesting some degree of ‘language uniformity’ (Djité, 2008). When interpreted through the prevailing theories of language policy and planning and language and development of the last decades (Coulmas, 1992: 25; Fasold, 1984: 7; Gellner, 1983: 35; Pool, 1972: 213), one is tempted to conclude that the issues of development plaguing African countries (i.e. national unity, political stability, economic growth and good governance) would not stand in the way of countries that have made the pragmatic choice of ‘instrumental and operational efficiency’ (Fishman, 1968 – Fishman’s concepts of ‘nationalism’ and ‘nationism’ are discussed in Chapter 6).

What follows suggests that the linguistic picture of the GMS is a complex one. This complexity goes a long way in providing some of the answers to the reasons why the countries in this sub-region continue to grapple with the same issues of development that African countries are faced with, especially in the areas of education, health, the economy and governance.

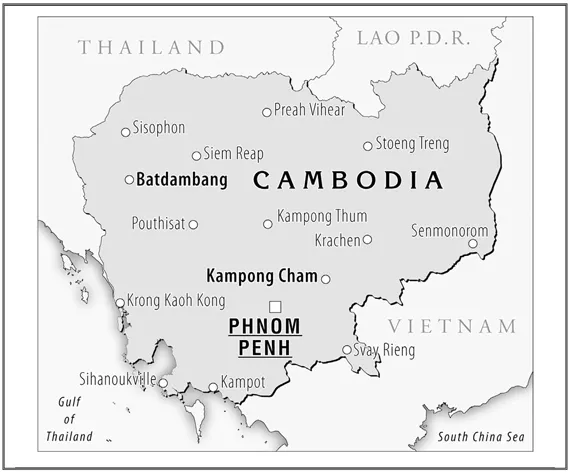

Language and Development in Cambodia

Cambodia is bordered by the Gulf of Thailand on the southwest, the Lao PDR on the northeast, Thailand on the northwest and west, and Viet Nam on the southeast and east (see Map 1.1). Its population was estimated at 14.8 million people in 2010.

Some 22 languages are spoken in the country. Khmer, the national and official language, has its own script, âkkhârâkâm khémârâ phéasa, informally known as ‘aksar Khmer’, a segmental writing system based on consonants, with obligatory vowel notation. Although it has influenced and been influenced by neighbouring languages, such as Thai, Lao and Vietnamese, due to Sanskrit and Pali influences, Khmer differs from the latter in that it is not a tonal language. Estimates of the ethno-linguistic groups living in the country vary between 20 and 40. Apart from the Muslim Cham – also referred to as ‘Khmer Islam’ – and the Chinese and the Vietnamese, whose populations are in the hundreds of thousands (Kosonen, 2005, 2007; Leclerc, 2009a; Neou Sun, 2009), all other ethno-linguistic groups are small. Statistics place the number of Vietnamese in Cambodia at 2 million or 5% of the total population, while the Chinese make up only 1% of the population. All other ethnic groups put together represent 4% of the population. A significant number of Cambodia’s minority groups live in remote highland provinces, where the literacy rate is estimated at only 5.3%. Some of these, such as the Brao and the Kraveth in the Ratanakiri province, are related to those living in southern Lao PDR, and were artificially separated from the latter by the border demarcation imposed by the French colonisers in 1903. Other indigenous people, such as the Khmer Leu or Choncheat (also known as hill tribes or highlanders. They call themselves ‘Choncheat’, hence my preference for this term), living in the northeast highland area and other areas of the country, are mostly illiterate and poor. As in the Lao PDR, education and economic development programmes have been aimed at settling the Choncheat outside their original villages and transforming their methods of agriculture and their general lifestyle, which was seen as backward (White, 1996). Two new provinces, Ratanakiri and Mondulkiri, were created in 1959 and 1960, respectively, in pursuance of a general policy of integration of the Choncheat into Khmer society.1 The government then started introducing Khmer culture to the indigenous people, as part of a five-year development plan. Then came the Khmer Rouge, who simply banned their cultural practices and language altogether.

Map 1.1 Map of Cambodia

Khmer is the dominant language, comprising approximately 90% of the population, making it one of the least diverse polities in southeast Asia. Cambodians are 95% Theravada Buddhists, but have Animist, Christian and Muslim minorities (5%).

Language and Development in the Lao PDR

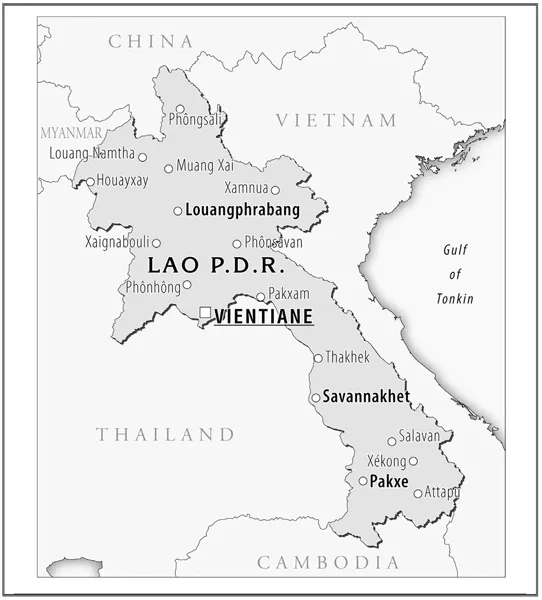

Once known as Lan Xang or ‘the Kingdom of a Million Elephants’ (founded in the 13th century), the Lao PDR is a small, landlocked and ethnically diverse country of 6.32 million people. Expanding at average growth rates of between 2% (World Bank, 2005) and 2.8% per year (GoL, 2005), one of the highest in southeast Asia, the population of the Lao PDR is expected to double by 2024. The country has a total land area of 236,800 km2, stretching more than 1700 km from north to south, 100–400 km east to west, at the centre of the GMS. Bordering China and Myanmar in the north, it sits between Thailand (on the other side of the Mekong River) in the west, Myanmar in the northwest and Viet Nam in the east. More than two-thirds of the country (70%) is mountainous, with 47% forest cover (see Map 1.2).

The population of the Lao PDR is 85% Buddhist and 15% Animist, 23% urban and 77% rural. As in Cambodia, Myanmar and Viet Nam, poverty in this country is mainly regional, rural and ethnic related, raising issues of equity and justice. Almost 70% of the total population and 90% of the ethnic minorities live in rural areas (eStandardsForum, 2008:1). They are mainly subsistence farmers (83%) and poor (46%). Four major ethnic minority groups are found in the Lao PDR:

Map 1.2 Map of the Lao PDR

(a) The Lao Tai (formerly Lao Loum) occupy the lowland plains and the Mekong river valley and constitute 66.7% of the population. This group, which comprises the Lao, the Lue, the Phou Tày and the Tai, has historically enjoyed a dominant position in society in the Lao PDR.

(b) The Mon-Khmer (formerly Lao Theun), comprising about 20.6% of the population, occupy the lower mountain slopes and are thought to have been the first inhabitants of the Lao PDR. This group includes the Brao, the Katang, the Katu, the Khmou, the Lamet, the Loven, the Makong, the So and the Ta Oy.

(c) The H’Mông-lu Mien (formerly Lao Soung) occupy the higher mountain slopes and make up 8.4% of the population, include the Huoay the H’Mông and the Yao.

(d) The Chine-Tibet (formerly Lao Soung) occupy the higher mountain slopes, constituting about 3.3% of the population. This group comprises the Akha, the Lahu and the Sila.

Together, these ethnic groups are said to make up 48% of the total population and live largely in rural areas. There are several other marginal ethnic minorities in the Lao PDR, also living in rural areas, as well as the Chinese, Vietnamese and other south Asians, concentrated in urban areas.

The number of languages spoken in the Lao PDR is a matter of debate and estimates range from 132 (Chazée, 1999) to 86 (Ethnologue, 2005; Kosonen & Young, 2009), and 82 (UNESCO, 2008) down to 49 (Lao PDR 2007) or even 47 (National Statistical Centre, 1997). Enfield (2006b: 698) believes that there are ‘around 70 [ethnic groups] and around 120 distinct languages’, with Mon-Khmer languages being the oldest to have been spoken in the country.

The dominant language, Lao, with more than 3 million first language speakers, is the official language. Lao (or Laotian) belongs to the Tai-Kadai language family, which also includes Thai, Shan and languages spoken by smaller, related ethnic groups in Laos, Thailand, Burma, southern China and northern Viet Nam. Lao is a concise language. Most of its basic words have only one syllable. Prefixes and combinations of basic words are used to make more complex meanings. Multisyllable words, mainly originating from Sanskrit, are generally used in religious, academic and government texts. The sentence structure is also quite simple. The Lao script, introduced during the time of the Angkor Empire, is based on Sanskrit, through Khmer, and the lexicon shows considerable borrowings from Pali and Sanskrit, through Buddhist philosophy and religion (Kosonen, 2005). Lao is spoken not only in the Lao PDR, but also by some 20 million residents of northeast Thailand, in an area called ‘Isaan’, where some differences, mainly tonal, have developed over the course of history.

Khmu is by far the largest ethno-linguistic minority with some 11% of the national population, followed by H’Mông, with around 8% of the total population (Lao PDR, 2007). Khmu and H’Mông have officially sanctioned Lao-based scripts, both of which have not been widely used. Both languages also have Roman orthographies. While the H’Mông actively use the Roman orthography in the community in the Lao PDR and especially overseas, the Khmu tend to use both orthographies (Lao-based and Roman-based) side by side (Enfield, 2006b: 485). Kosonen (2005: 128) suggests that ‘the number of different ethno-linguistic groups may actually be higher than what the Ethnologue (2005) states’, and believes that there are at least nine other languages, each spoken by more than 100,000 people or around 2% or more of the total population. The population speaking minority languages throughout the country constitutes about half of the total population (National Statistical Centre, 1997; UNFPA, 2001), and some suggest that the dominant language group, Lao, may in fact be spoken by less than half of the population, depending on the definition of ethnic minority and the interpretation of statistical data (Chazée, 1999; Kosonen, 2005, 2007). Chazée (1999: 7, 14) claims that only 35% of the Lao population are first language speakers of Lao Loum or the lowland Lao variety of the language.

As is usually the case in other multilingual contexts, speakers of minority languages in the Lao PDR, especially the upland peoples, tend to be multilingual, while lowland-dwelling people, speakers of the majority language, tend to be monolingual. This is compounded by widespread internal migration, resulting in a shift to Lao. In 2001, the Lao National Literacy Survey (LNLS, 2001) found that 71.1% of the total population spoke Lao at home, while 27.3% spoke different minority languages.

The Lao PDR has not named one variety of Lao as the official language of the country (as in Thailand where Central Thai is the official language); however, the Vientiane variety is becoming the unofficial national language. Lao citizens of non-Lao or other Tai ethnic groups who study or work in the capital often try to speak Lao with a Vientiane accent. Other languages with a significant presence in the Lao PDR are Thai and Vietnamese, as the country’s longest borders are with Thailand to the west (1800 km) and Viet Nam to the east (2130 km).

The most serious challenge that the Lao PDR faces is human resource development. In the Annex to a letter dated 2 June (E/2008/78), addressed to the President of the United Nations Economic and Social Council, Mr Kanika Phommachanh, Permanent Representative of the Lao PDR to the United Nations, writes that the Lao government considers five areas crucial. These are: poverty eradication, education, health, gender equality and sustainable development (Phommachanh, 2008: 2). Thus, the Lao PDR cannot afford to ignore its ethnic minorities, especially not when these minorities make up at least 48% of the total population. There needs to be significant upgrading of the skills of all the people across the country, through improvements in the enrolment, retention and quality of education in the Lao language and in the languages of the ethnic minorities.

Language and Development in Myanmar

Political events or non-events and natural disasters are the enduring images through which we tend to perceive developing countries like Myanmar, in what we otherwise believe to be a globalised world. Hence, many people will perhaps have heard about Pyidaungsu Thamada Myanmar Naing-Ngan Daw, or the Union of Myanmar (formally the Union of Burma)2 only after the 1988 uprising, the ‘stolen’ multiparty legislative elections of 1990 (see Chapter 5 for further details), the brutal suppression of demonstrations in September 2007 – when activists and Buddhist monks took to the streets in protest after unexpected increases in the price of fuel and other basic commodities – or the 2008 cyclone3; all of which are a poor reflection of the scholarly and media attention afforded this country over the last four decades. Taylor (2005: 1) writes that ‘to understand modern Myanmar, one needs to appreciate the various pathways to the present that have come together to create the country’s current condition’. This section aims to do exactly that, in order to get a clear understanding of the underlying issues facing Myanmar, at least insofar as the question of language is concerned, and in terms of how it affects the critical areas of education, health, the economy and governance.

In saying that, I wish to point the reader to the usual caveat in discussing Myanmar. Indeed, the literature is replete with warnings on the paucity of reliable data to study Myanmar. In Perry’s words (2007: 13), ‘the problem of the unrecorded is generally more important than that of the misrecorded’. Myanmar is a country where one is confronted with serious restrictions when attempting to collect data of any kind; whatever data are made available need to be treated with extreme caution. Ironically, I have found language, or the lack of proficiency in the local languages, to be part and parcel of this limited capacity to understand the people, the place, and the socio-political and sociolinguistic realities of Myanmar.

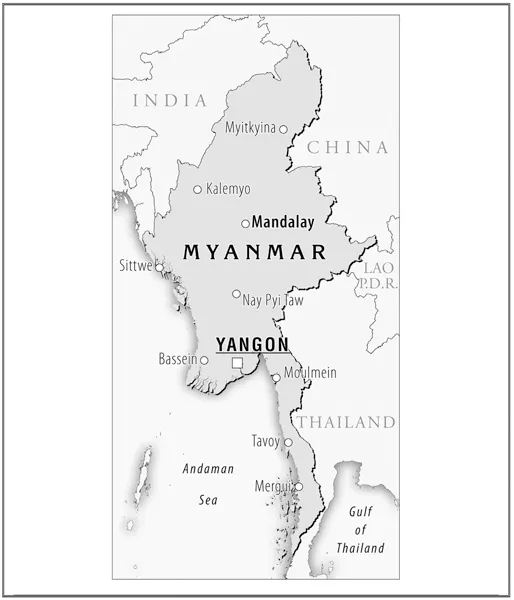

Located on a strategic crossroads in Asia, Myanmar is a diverse country of 50.02 million inhabitants, growing annually at a rate of 0.8% in 2008 (World Bank’s World Development Indicators, 2008). Covering a total area of 678,500 km2, the Union of Myanmar (henceforth Myanmar) is the creation of British imperialism (see Chapter 5 on ‘Language and Governance’ for further details on the creation of present-day Myanmar). Bordered by the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal in the south and southwest (2300 km), Myanmar shares common borders with Bangladesh (271 km) on the west, India (1338 km) on the northwest, China (2107 km) on the north and northeast, the Lao PDR (238 km) on the east and Thailand (2107 km) on the south and southeast (see Map 1.3) (figures based on Han, 2004).

The population of Myanmar is estimated at about 30% urban and 70% rural. Most people in Myanmar are Theravada Buddhists (90%). Christians and Muslims are equally represented in the population (4% each), while Hindus represent about 2% of the population. Many members of these religious denominations, some 12.6% of the population, still practice traditional beliefs.

It is not clear exactly how many languages are spoken in Myanmar, in part because no formal linguistic survey has ever been carried out in the country. Estimates vary between 100 languages (Kosonen & Young, 2009) and 200 languages. Gordon (2005) lists 108 languages in the country, many of which are also spoken in neighbouring countries. Quoting Ethnologue 2004, Taylor (2005: 2) concurs, suggesting that ‘there are more than a dozen linguistically distinct ethnic groups with perhaps as many as 100 different dialects and sub-groups’. However, according to Ang Cheng Guan (2007: 124), Myanmar has eight major ‘ethnic races’ (i.e. the Kachin, Kayin, Kayah, Chin, Mon, Rakkhine, Shan and Bamar) and ‘some 135 minorities’. The majority language group, the Bamar, accounts for 70% of the total population. The Shan make up more than 10% of the population. Other important language groups are the Arakanese, the Karen (Sgaw, Pwo and Pa’o), the Mon and the Jingpho (Leclerc, 2009c). A number of large ethnic groups live in States named after their group (e.g. the Chin State, the Mon State and the Shan State). Altogether, ethnic minorities are believed to constitute about 30% of the total population of Myanmar.

The official language of the country is Myanmar (see Chapter XV, Paragraph 450 of the Constitution), the language of the majority Bamar (68–70%). Other important language communities comprise the Han Chinese (3%), the Indians (2%), the Karen (7%), the Rakhine (4%), the Shan (9%), the Mon (2%), the Yangbye (2.2%) and the Kacin (1.5%). Until colonial times, only Bama/Myanmar, Mon, Shan and the languages of the ancient Pyu kingdom of northern Myanmar were written. However, writing systems have now been developed for the languages of the Karen, Kachin and Chin peoples.

Map 1.3 Map of Myanmar...