- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This collection is a resource book for those working with language disordered clients in a range of languages. It collects together versions of the well-known Language Assessment Remediation Screening Procedure (LARSP) prepared for different languages. Starting with the original version for English, the book then presents versions in more than a dozen other languages. Some of these are likely to be encountered as home languages of clients by speech-language therapists and pathologists working in the UK, Ireland, the US and Australia and New Zealand. Others are included because they are major languages found where speech-language pathology services are provided, but where no grammatical profile already exists.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Assessing Grammar by Martin J. Ball,David Crystal,Paul Fletcher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Linguistica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 On the Origin of LARSPecies

David Crystal

The origins of LARSP lie in a serendipitous encounter with a language-delayed child, at a time when a linguistically informed analysis of language was not a routine weapon in the speech pathologist’s armoury. In Britain, it was not until 1972 that a government report on speech therapy services (the Quirk Report) made a statement that now seems blindingly obvious, but which at the time indicated the distance still to be travelled in clinical training and practice1:

the would-be practitioner of therapy… must in future regard language as the central core of his basic discipline.

The consequence was an immediate raising of the profile for linguistics, as the relevant science of language. A new climate formed and a clinical linguistic perspective became routine. LARSP, expounded in 1976 in the book The grammatical analysis of language disability,2 was part of that climate. But its origins lie a decade before, in that chance encounter.

The Department of Linguistic Science at the University of Reading was established in 1965. One of my roles was to teach courses in the structure of English and child language acquisition, and so, when a phone call came through from the Royal Berkshire Hospital, just down the road, it was put through to me. It was from the audiologist, Dr Kevin Murphy, who was hoping that there was someone who could visit his department to advise on the assessment of a 3-year-old child whose speech was puzzling them. There were no hearing problems, it seems, and intelligence and social skills were normal, but she wasn’t saying very much, and when she did speak her utterances evidently sounded immature.

I spent an afternoon observing a session with her therapist. It was the first language-delayed child I had ever seen, but her language output was immediately recognizable to anyone familiar with the limited but growing literature on language development in children. Asked for my opinion about what was going on, I gave a report which (if I were giving it today) would say that this child was making slow progress at Stage II, with several isolated phrases, verb-related gaps in clause structure, no clause element expansion in the direction of Stage III and a worryingly high proportion of minor sentences at Stage I. But this was not today: it was 1968. And as I continued with my description of the child’s grammatical difficulties and her developmental level, it was evident that my listeners had no idea what I was talking about.

We took time out to discuss the problem. Grammatical analysis, it appeared, had not been part of the training of any of the professionals in the room. They had a vague memory of ‘doing grammar’ in their school days, but that had not been a particularly pleasant experience; they had forgotten most of it, and in any case it didn’t seem to relate to the practical demands of the clinic. Nor had they ever been given a course on child language development. That was hardly surprising. Child language studies were in their infancy in the 1960s. There was no journal of child language (that did not begin until 1975), no child language association (that was 1970), and the major books that would one day define the subject were yet to be written (Roger Brown’s A First Language, for example, wasn’t published until 1973). I well recall the difficulty of finding material for students to read, in those days, and – in a pre-CHILDES era3 – getting hold of audio examples of real children to demonstrate developmental reality. I spent many hours recording my young children, as a consequence, and I know several other linguists who were doing the same.

LARSP, I can see now, was born on that afternoon. I was asked to write up my observations in a report, and present it to a group at the hospital. I did so, giving them a handout which had primitive levels of development (what would later be Stages I to V) illustrated by a few types of construction. The child was evidently about two years grammatically delayed. My session included a basic grammar tutorial about clause and phrase structure. The data from the child was analysed and located at the appropriate points. It was possible to see a pattern: where she was. It was also possible to see the deficit: where she ought to be (for her age). And because the material was organized into developmental stages, it was possible to address the question that was foremost in everyone’s mind: how do we get her from where she was to where she ought to be? The principle of following normal development was already well established in paediatric circles, so it was possible to suggest to the speech therapist that the next session should focus on structures which would first consolidate the stage where the child was (introducing verbs, in particular), and then integrating phrase structure within clause elements. A remedial programme was agreed, and therapy began. It is no surprise today, several thousand interventions later, to know that it worked. But at the time, the fact that the therapy was principled, that the child made progress, and that the procedure was generalizable to other patients with language disability (adults as well as children), produced reactions of genuine surprise, delight and relief.

It was grammar that had to be the primary focus of attention, and rightly so. Although the child I had seen evidently had an immature vocabulary and pronunciation, it was her grammatical difficulties which needed the most urgent treatment. This is because grammar is the key to understanding language disability. Vocabulary, because of its huge scope (tens of thousands of words to be learned) is sometimes said to be the primary goal of therapy, and it has certainly taken up a huge amount of testing time. But vocabulary without grammar is a dead end. Without a command of sentence structure, it is not possible to make sense of words. Words by themselves are entities with uncertain meaning. A one-word sentence has many possible interpretations. A word such as apple has several competing meanings (‘fruit, computer, Beatles...’). Only by putting words into sentences is it possible to say which meaning we wish to convey. All the structures of grammar, from the largest clauses to the smallest word-endings, are there to help make sense of our words. Procedures for other aspects of language are important, of course, but grammar remains at the centre of clinical enquiry, as the dimension within which semantic and phonological observations need to be integrated. That is why LARSP was the first kind of procedure to be developed.4

As a young linguist, interested in the potential of linguistics to be useful as well as fascinating, I found the clinical domain enthralling and enticing. A two-track process of development followed: on the one hand, it was crucial to gain as much clinical experience as possible, to test the hypotheses about grammatical delay, and here the hospital and local speech therapy clinics played a critical role; and it was essential to consolidate the analysis, filling it out on the basis of contemporary research findings, establishing norms and integrating it into a single procedure. This second task took much longer than I was expecting, because in the early 1970s child language research was a rapidly expanding field, and many new developmental findings had to be incorporated into the procedure. At the same time, it was evident that there were huge gaps – areas of grammatical development where little or no empirical research had been done. I initially supplemented the research literature with data taken from samples of my own children, who had by this time (a boy born in 1964, a girl born in 1966) gone through all the relevant grammatical stages without incident. But a more systematic approach was needed. The principle of many heads making light work obtained. The cavalry had arrived in the department, in the form of Michael Garman and Paul Fletcher, and with their overlapping interests and expertise a fuller picture of grammatical development to age three soon emerged. The later stages of acquisition were less well studied, and our Stage VII is really no more than a placeholder, reminding people that there is grammar still to be learned after age five, but this didn’t bother us. Most patients were going to be at a much earlier stage, and if any of them managed to reach Stage VII they would hardly need the help provided by a LARSP. The same point applied when using the chart to work with adult aphasics.

By early 1974 we had an account that we felt was developmentally robust. We took it out on the road, giving in-service courses to groups of speech therapists in various parts of the UK, all of whom were very keen to take on board this early encounter with a linguistic perspective. The benefit for us was that many in our audiences were highly experienced clinicians, and their comments helped us shape the final version of the chart as well as giving us confidence about our judgements.

Just as important as the developmental side of the project was its practical purpose. There was no point in working up a procedure that clinicians and remedial teachers would find unusable. The mid-1970s was a period when formal language teaching had disappeared from British schools (it had gone from most school syllabuses by the mid-1960s)5 and well before the recommendations of the Quirk report had been implemented in speech therapy training courses. There was a limit to the amount of grammatical apparatus that professionals would be able to assimilate, and real constraints on the amount of clinical time it would take to use a new procedure. The shortage of speech therapists meant that most patients were being seen for perhaps half an hour a week, with heavy caseloads leaving little time for analytical reflection. Feedback from clinicians made it clear that they wanted a procedure which would fit on one side of a sheet of paper.

As linguists, we had two choices to make. Which grammatical model to choose? And how much grammatical detail to introduce? After much debate, we used a model in which a clear distinction is made between sentence structure (syntax) and word structure (morphology) – a highly relevant clinical distinction. Complex sentences are analysed into sequences of clauses; clauses are analysed into a series of elements (Subject, Verb, Object, Complement, Adverbial); and clause elements are represented by phrases (such as noun phrase, verb phrase, prepositional phrase).6 We reduced the amount of grammatical detail by focusing on a small number of developmentally salient constructions and making a copious use of the category ‘Other’. We experimented with several designs before settling on the final version, which did, happily, fit on to a single page.

What kind of procedure had emerged? We had spent some time looking at the tests and procedures that were already being used in relation to other areas of child development. It was immediately obvious that grammatical development was unlike anything else: for a start there were too many variables operating simultaneously – formal choices in clause and phrase structure (SV, DN, etc), sentence functions (statement, question, etc), morphology (-ing, -ed, etc) and patterns of interaction (especially questions and responses). It would never be possible to reduce these to a single ‘test’ score. The notion of a profile of performance, already used in linguistics (in such areas as stylistics), seemed the only sensible way to proceed. And it was evidently going to be desirable to bring together the four chief clinical desiderata: screening, assessment, diagnosis and therapy. Bearing in mind, also, the fact that many children with language problems were being managed in school (rather than, or as well as, in a clinic), it was important to introduce an educational perspective. How were all these variables to be combined?

Diagnosis seemed a distant goal, given the lack of clinical case studies. In any case, the broad diagnostic categories already being used (‘language delay’, ‘language disorder’) were enough to be getting on with. It was likely that it would eventually be possible to establish a more refined set of diagnostic categories, identified by their grammatical symptomatology, but this was not going to be possible until a large number of individual patients had been thoroughly investigated using a standard sampling procedure – and, moreover, over a period of time. Assessment, and its first cousin, screening, seemed more realistic immediate goals, along with the notion of remediation (a term that seemed to straddle clinic and classroom), so these three elements influenced our choice of the name for the procedure.

A good acronym was evidently critical. Acronyms were everywhere in the clinical domain (WISC, PPVT, RDLS...), and we appreciated the value of a succinct label in everyday discourse. Fortunately, the initial letters of Assessment, Screening, and Remediation, along with P for Procedure, formed a pronounceable unit, ARSP. That was the easy bit. The more intriguing question was which letter to use to introduce the acronym. G for Grammar was the obvious choice, but GARSP (pronounced ‘gasp’ in Received Pronunciation) had the wrong connotations and elicited hilarity from anyone we mentioned it to – as did GRARSP. It is always wise to try out acronyms in real sentences before choosing them, and it seemed somewhat inelegant to talk of a patient having been GRARSPed. We settled for LARSP, where L stood for Language. Today, with several other profiles and procedures around focusing on other aspects of language (semantics, phonology, etc), that choice feels too general. LARSP does not deal with all aspects of language. But in the mid-1970s, it seemed a reasonable decision. Grammar was virtually synonymous with the notion of language in the minds of therapists, and the change of direction from ‘speech’ to ‘language’ (which eventually became formally incorporated into the official nomenclature of the profession in the UK) was chiefly associated with a move from pronunciation to grammar. (In the event, the application of LARSP to other languages led to the some authors replacing the initial letter, as several chapters in this book illustrate.)

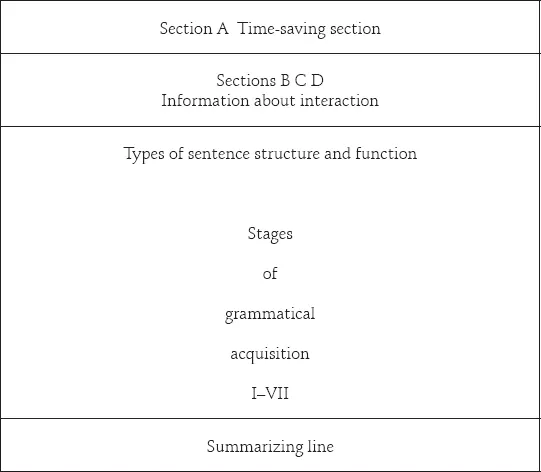

The structure of the chart reflected its utilitarian purpose (see Figure 1.1). The main types of organization in sentence structure and function are represented under various headings laid out horizontally on the chart. The main stages of grammatical acquisition are laid out vertically on the chart, beneath the thick black line. The main patterns of grammatical interaction between therapist/teacher and patient/pupil are summarized above the thick black line, in Sections B, C and D. The bottom line of the chart contains certain kinds of summarizing information, and Section A is included primarily as a time-saving device in using the procedure. We quickly learned that an awful lot of time was being wasted by clinicians struggling to analyse utterances that any experienced grammarian would see straight away were not worth the effort because they were incomplete, ambiguous or whatever. There was a natural tendency to want to analyse everything, and it’s an important moment when one realizes that a significant feature of an assessment is the proportion of utterances that cannot be given a sensible grammatical analysis. Section A, with its categories of Unanalysed and Problematic, and their five subdivisions, was partly intended to take the worry out of the situation, as well as being clinically informative in its own right.

Figure 1.1 Outline structure of the LARSP chart

Sections B and C reflected our sense that it was crucial to alert clinicians to the importance of the way they talked to their patients. An early observation had been that two of the most popular question stimuli were actually hindering rather than helping patient response: ‘What doing’ (e.g. What’s the man doing?) and ‘What happening’ (e.g. What’s happening in the picture? Tell me what’s happening). These questions demand verbs if they are to be answered (He’s running, A man’s jumping), and as most of the patients we were analysing had early problems with verbs, these stimuli would only add to their difficulty in replying. An important prior remedial procedure was to teach some verbs, first by imitation, then by using forced alternative questions (Is he running or jumping?), before proceeding to the open-ended questions of the ‘What doing’ type. The interactive section of the chart was designed to draw attention to problems in this area – and in particular to the fact that therapists and patients are engaged in a dialogue, and that any assessment or decision about therapy needed to monitor the evolving discourse relationship between the participants. It is not only the patient’s use of language which provides the basis of an assessment; the therapist’s use of language has to be taken into account too.

If the chart had been designed a decade later, these sections would probably have looked very different. During the 1980s, pragmatics developed as a branch of linguistics, with its focus on the intentions behind a speaker’s choice of utterance and the effects on the listener that these choices convey. Discourse linguistics was also increasingly attracting attention. Both of these perspectives had begun to influence child language studies, and the importance of the type of adult response to a child utterance (e.g. whether the parent expands the child’s sentence) had been highlighted as a significant factor in language learning. The second edition of the chart recognizes these trends by adding a Section D, which records t...

Table of contents

- Coverpage

- Titlepage

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Introduction

- 1 On the Origin of LARSPecies

- 2 LARSP Thirty Years On

- 3 ‘Computerized Profiling’ of Clinical Language Samples and the Issue of Time

- 4 HARSP: A Developmental Language Profile for Hebrew

- 5 Profiling Linguistic Disability in German-Speaking Children

- 6 GRAMAT: A Dutch Adaptation of LARSP

- 7 LLARSP: A Grammatical Profile for Welsh

- 8 An Investigation of Syntax in Children of Bengali (Sylheti)-Speaking Families

- 9 ILARSP: A Grammatical Profile of Irish

- 10 Persian: Devising the P-LARSP

- 11 Frisian TARSP. Based on the methodology of Dutch TARSP

- 12 C-LARSP: Developing a Chinese Grammatical Profile

- 13 F-LARSP: A Computerized Tool for Measuring Morphosyntactic Abilities in French

- 14 Spanish Acquisition and the Development of PERSL

- 15 LARSP for Turkish (TR-LARSP)

- Subject Index

- Author Index