![]()

1 Texts in the Fabric of Life

… a great deal of our verbal interaction does involve clearly defined speech events.… We are frequently involved in uses of language in which we only need half a dozen words, and we can tell immediately what the context of situation is.

Halliday and Hasan (1985: 38)

Introduction

This chapter outlines the centrality of texts in our lives: how texts are bound up with and constitute meanings for participation in society. We are born into a web of language use in cultural contexts. We are members of social groups or communities and together we take part in social practices, frequently with language. The use of language is vital for our social relationships. The patterned nature of language as texts enables us to participate socially in speech and writing based on familiarity with people, purposes and contexts of use. Our socialisation experiences in daily interactions familiarise us with cultural meanings – a lot of the time with language. Language is one of our significant semiotic systems. In traditional language teaching, language was extracted from people’s experience and reduced to objects for analysis. Pedagogies were designed to reassemble language objects for communication. Social theory constructs curricula around learners’ familiarity with texts. As language has such a significant role in the mediation of cultural meanings, texts are central to learning. This is the practical reason for building a curriculum around the texts of social practices.

Life with Language: The Texts of Social Practices

Texts are integral to everyday life. We organise our lives and those of others with numerous spoken and written texts – greetings, instructions, news, emails, telephone calls, calendars, timetables and diaries. Invitations, weather forecasts, sporting programmes and television shows influence our decisions, actions and events. We undertake tasks with shopping lists and in response to letters, emails and SMS messages. We share and reflect on experiences in Facebook, letters and postcards, in conversations and telephone calls. Texts are so much part of our routines and actions that most of the time we are not aware of using them or of the language which constitutes them: they are threaded into the social fabric of relationships, work and leisure.

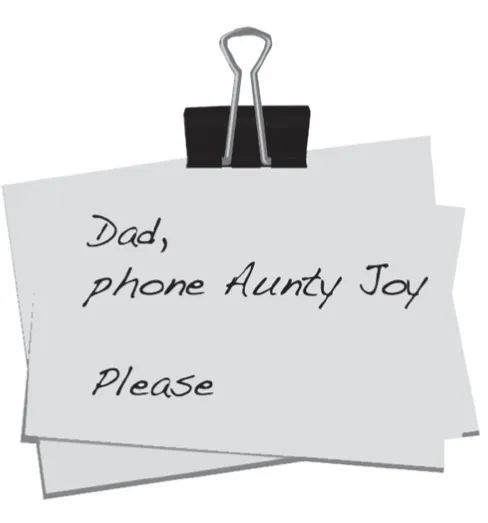

Text 1.1 A telephone message

Texts embed information about people, places and events. A telephone message records with brevity a great deal of information. My daughter took a telephone call for me yesterday and left the message shown in Text 1.1. The message carries evidence of our family relationships – child, aunty and sister. It shows the informality of my daughter’s relationship with me. It contains expectations of action – to telephone the caller. The contextual information in a telephone message – which might include who called, for what purpose and at what time – can enable recognition of the source, context and purpose of the message, and give instructions on what actions to take. The message displays social function and purpose for those familiar with the use of iPhones and social media in society.

When we hear or read a text like this we attempt to interpret the social information in the text. The transcript in Text 1.2 is from a service encounter, an event which involves purchasing something. This service encounter takes place in a theatre before a performance. The interlocutors are a theatre attendant (A) who is selling programmes for a drama performance and a theatre-goer (B) who is considering buying a programme. The theatre-goer enquires about a programme for the performance. As I read the transcript I reconstruct the situation in which it occurs. A theatre attendant offers a theatre-goer assistance, who responds with a question about price. As it is nine dollars the theatre-goer asks to look at the programme first to see if it warrants that much money. The attendant then asks what the theatre-goer has decided. The theatre-goer expresses the wish to purchase it. Payment is made, change is given and greetings are exchanged. Although the transcript displays the interaction out of context, we are able to reconstruct the action from the text. Text, actions, material objects and space are integrated. The transcript illustrates the alignment of language with human activity and physical space. Language use is integral to the actions of making a purchase. Success in spoken interaction results from participants’ understanding of what is going on, anticipation of response and prediction of the nature of the response.

| A | Hi there, can I help? |

| B | Um, how much are programmes? |

| A | They’re nine dollars. |

| B | Oh, right! |

| | Um, do you mind if I just have a look at it first? |

| A | No, no, that’s fine. Go ahead. |

| B | Oh, thanks. [Few moments’ pause while B looks at programme] |

| A | So, what do you reckon? What’s the verdict? |

| B | Um, yeah, I’ll take one thanks. |

| | Just got to find my money. |

| | Oh, there you go. |

| A | Thank you, from twenty, that’s 10 and 11 dollars change. |

| B | Thanks |

| A | Thank you. See you later. |

| B | Yeah, seeya. |

Text 1.2 Service encounter: Buying a programme at the theatre

We observe, hear and produce texts which convey meanings about contexts, participants and proceedings. We have learned these in our cultural socialisation. From multiple encounters with language we distinguish meanings in language patterns and develop expectations of how language is used for specific purposes. We respond to greetings, answer questions, email responses and read instructions for buying a ticket from a machine. We observe the texts around us – how people talk together, write to each other, read messages and document work. In conversations we monitor minutely the actions and reactions of speakers and fine-tune our language choices for different purposes. Different domains of human activity have different texts. In workplaces we adopt technical language and subject-specific discourses. In relationships we distinguish socially appropriate terms. For participation in events, we observe and draw upon the texts of others. For the expression and composition of our own texts, we seek advice or help from experienced others. Over time we develop discourses appropriate to our roles, to our relationships and to our goals.

Movement from one domain of social activity to another requires learning new texts – learning the specific functions, the local meanings and wordings for the comprehension of, and contribution to, activities. For example, when children go to school they need to learn language for understanding and taking part in school procedures and in defined classroom activities. They experience and learn to produce new texts: texts for participation, for gaining attention and for responding appropriately to instructions. They learn to use the formal discourses of education for school subjects and for specialised topics which have characteristic ways of organising information with maps, diagrams and graphs. Children’s and students’ engagement in new practices socialises them into uses of appropriate discourses (Mickan, 2006).

Familiarity with texts is essential for relationships, work and leisure. Texts have a direct influence on our behaviours. A weather report in the daily newspaper influences the clothes we wear, the transport we take, the plans we make with family or friends. We change menus, venues and programmes in response to weather forecasts. A shopping list directs movements and interactions in the supermarket or marketplace. A written or voicemail telephone message requires follow-up telephone calls or meetings. Texts enable us to make sense of our experiences and of the experiences of others, such as when we listen to someone retelling an event or read a travel book. The ubiquity, propinquity, utility and significance of texts in our lives make them familiar units for the design of curricula and useful organisers for teaching activities.

Social Practices, Texts and Meanings

Language is a pre-eminent system for making meanings in human culture. It is associated with other systems for making meaning, such as physical gestures, visual representations, material objects, spaces, sounds and movements. Texts are units of meaning. As we grow up we become familiar with meanings of numerous texts. In spoken language we use tone, gestures and volume together with the choice of wordings to vary meanings and to convey nuances of meaning. For written language the signs on the page or screen are of importance in the creation of targeted meanings: the wordings and fonts and layout contribute to the meanings of a text. Language as text is a normal part of sharing meanings with others and making sense of experiences.

Our normal experience of language is to make sense with it. Learning to make meanings is central to a social theory of language. Traditional language education analysed language in linguistic terms as formal grammar not as a system for the expression of meanings. While recent pedagogies such as communicative language teaching and task-based approaches have highlighted communication in language learning, form in terms of grammar, and function in terms of meaning, are treated separately in exercises and explanations. Different conceptions of language underpin traditional language pedagogies and social theory pedagogy. One views language as an object to be described, analysed and studied. The other conceives language as a system for making meanings. Learning to mean is different from learning about rules for language use and the application of grammatical rules out of context. Making meaning with language is not part of doing transformational exercises. Learning language use is not translating lists of sentences or doing grammatical insertion exercises which make no sense.

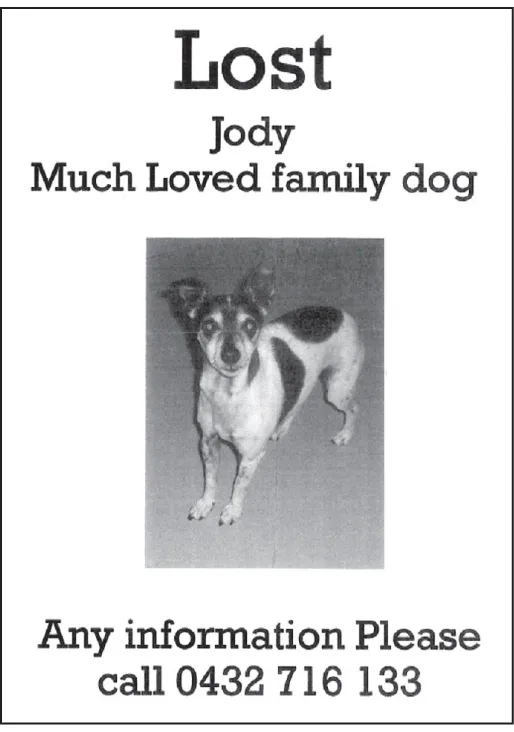

Encounters with texts evoke specific social meanings. Halliday (1975: 124) points out that ‘Text represents the actualization of meaning potential’. Particular word combinations together with page layout and pictures accompanying a text suggest particular meanings. Our normal response to signs and sounds of language is to make sense, to seek meanings. A flyer reproduced in Text 1.3 was put through our letterbox. It deals with a set of culturally related circumstances. When a pet cat or dog goes missing, owners often seek neighbours’ help in finding the animal by posting flyers through letterboxes or on fences and trees with information about the loss. In this example, the message is expressed in the wording and visual layout of the text. The text format is printed as a public notice so people recognise its purpose. I construct the dominant meanings in the text as follows:

Text 1.3 Flyer requesting help to find a missing dog

• text type – flyer or poster advertisement to find missing pet dog;

• culture – dogs kept as pets;

• social practice of the text – find lost animal; appeal to community to assist in locating the pet;

• topic – pet dog, as opposed to wild dog;

• circumstance – from the perspective of the owners the dog is lost (possibly not the dog’s perspective);

• function of the text – a request for help to find the dog;

• relationships – sympathetic and trustworthy community members who understand owner–dog relationships;

• mode – this is a multimodal text, a written notice with a picture of the dog; the notice is circulated in a literate community; it is designed to reach a maximum number of people through duplication and circulation (primarily through people’s letterboxes);

• lexico-grammar – selection of wording creates meaning potential to achieve social purpose.

When I received the flyer I was abl...