![]()

Part 1

Experiential Learning through Community Engagement

![]()

1 Multilingual Learners and Leaders

Adrian J. Wurr

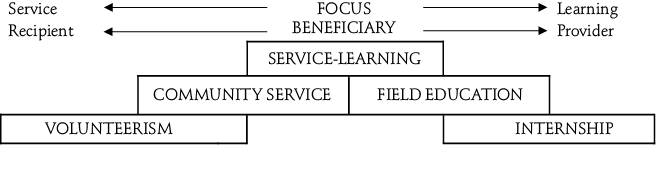

Experiential education programs encompass a wide range of curricula, from traditional internships, classroom-based learning in labs and teaching practicums to the community-based learning afforded by volunteering. As shown in Figure 1.1, internships and field experiences primarily serve as pre-professional training and career development opportunities for students. At the other end of the experiential education continuum, volunteer programs such as Alternative Spring Break provide direct-service opportunities for students to make a difference in their communities. The locus of activity often shifts between campus and community over the life of a project; most programs also move back and forth along the continuum over time. Indeed, almost any experiential education project can be crafted to emphasize outcomes at one end of the spectrum or the other in order to meet its defined goals.

This chapter will describe lesser-known programs in the United States that engage students of different ages and backgrounds in experiential learning activities that are most often described as service learning (SL), but that may share qualities with other types of experiential education. The purpose is to provide readers with a better sense of the range and scope of projects that are possible in different educational settings, while also introducing some of the supporting research and scholarship. All cases work with linguistically and culturally diverse populations to highlight the beneficial effects of engaging people from diverse backgrounds in meaningful activities toward a common goal.

Figure 1.1 Experiential education continuum Adapted from Furco (1996: 3). Reproduced by permission of the author

Literature Review

Learning outcomes

Earlier reports involving English language learners (ELLs) in SL provided some evidence of the ways in which language learners benefit from volunteering in the community, including positive outcomes in social, cognitive and affective domains. In the social domain, learning about the target culture (Bippus, 2011; Bippus & Eslami, 2013; Heuser, 1999; Seltzer, 1998; Steinke, 2009) is perhaps most prevalent and is supported by the social turn in language-learning theories. Cognitively, gains in academic writing skills (Hamstra, 2010; Wurr, 2002, 2009) are most often cited, given the frequent use of written reflection and the early adoption of SL by composition scholars (e.g. Adler-Kassner et al., 1997; Deans, 2000; Deans et al., 2010). Gaining a ‘confidence to contribute’ (Whittig & Hale, 2007) is frequently cited as a main outcome in the personal domain for ELLs who participate in SL (e.g. Bippus & Eslami, 2013; Perren et al., 2013; Rueckert, 2013; Steinke, 2009).

Recent research reports provide additional support for the proposition that SL can potentially enhance learners’ knowledge and use of all language skills. Askildson et al. (2013) found that international students enrolled in an intensive English summer program that included SL improved their English language proficiency at a rate that was three times greater than traditional classroom-based instruction:

According to this model, a standard intensive English program with the equivalent 25 hr of instruction per week and a total of 200 hr of instruction over 8 weeks should result in an average gain of 20 points. The pre- to post-test gains in the present study are more than three times greater than this predicted outcome and suggest the potential of a robust facilitation effect. (Askildson et al., 2013: 424)

Study Abroad and Intensive English Programs (IEPs)

An IEP program that I helped to administer at the University of Idaho involved international students in SL projects while studying abroad in the United States. The Central American Youth Ambassador (CAYA) program is one of several educational exchange programs sponsored by the US Department of State to bring aspiring youth leaders from around the world to study in America while participating in civic engagement and leadership programs. The goal of these programs is to create change agents who will have a positive impact on their communities while also fostering positive relations with future foreign leaders.

The first six months of the program were devoted to intensive English language lessons for the students at a neighboring college while they lived with American families in the community. The second half of the students’ year in the United States was devoted to specialized training in social entrepreneurship, leadership and civic engagement. Custom university classes and community-based field experiences focused on sustainable agricultural practices, since the university and the students’ hometowns were in agrarian settings. For example, one course taught by an education graduate focused on climate change and environmental systems. Students researched the topic online, attended guest lectures by university and community experts and volunteered on a local farm that promoted sustainable agriculture. The students also visited local nurseries and community gardens to better understand sustainable agriculture supply chains and volunteered with the largest environmental non-profit in the area, The Palouse–Clearwater Environmental Institute, helping with tree planting and wetland restoration projects. In the summer, CAYA students assisted with lessons at the University of Idaho’s McCall Outdoor Science School (MOSS), which provides hands-on environmental science lessons to thousands of K-12 students across the state every year. Most MOSS teachers are AmeriCorps members and graduate students. These AmeriCorps members complete graduate coursework in education and/or environmental sustainability, while volunteering full-time in summer and part-time during the school year. CAYA students also participated in a variety of cultural events, including serving as guest DJs on a local radio station, where they interspersed music with historical and cultural essays on their hometowns. They also performed traditional dances at local schools and civic organizations. In all, a total of 18 students in two cohorts completed a combined total of 5680 hours of community service over the two years in which the program operated, providing valuable service to communities that might not have otherwise been able to afford it.

Long-Term Impacts

What happens when these learners return to their home countries? Bickel et al. (2013) report on a 12-week online conversation course for CAYA alumni that is designed to provide a platform for further English language learning, youth engagement, social responsibility and community leadership. The student response was overwhelmingly positive, challenging the instructors’ ability to keep up with the conversation. Students proved adept at creatively using English across multiple online platforms and geographic borders to reimagine and project themselves as agents of positive social change and as emerging community leaders.

While the results from this study show that learners can and do apply the lessons they learned in the field to other settings and situations in the future, Cameron (2015) goes even further by investigating the impact of a single SL course for advanced IEP students three years later, providing evidence of long-term positive impacts on civic engagement as a result of ELLs participating in SL. Cameron finds that ‘a cycle for actualizing social justice emerges to show participants’ shift, post-service, from awareness to critical consciousness and on to continued action, with individual differences as a factor in determining current attitudes and behaviors’ (Perren & Wurr, 2015b: 26).

While Cameron’s study shows the long-term impact that civic engagement can have on the learners themselves, others have noted the generational effects that ELL service leaders can have on society as a whole. For example, Fajardo et al. (2014) note:

As Latina/o college students increase their community engagement, they inadvertently provide members of the community with leadership models and expanded networks in the college environment. This subsequently increases the community members’ chances for social mobility. The role of community engagement cannot be underestimated. (Fajardo et al., 2014: 153)

The bottom line here is that ‘global citizenship should be extended to include those who are traditionally regarded as potential recipients of service’ (Erasmus, 2011: 366).

K-12 ESL Settings

One of the best-kept secrets in the literature on SL has been the Coca-Cola Valued Youth program developed by the Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA) in San Antonio, Texas. While the program has received its share of funding and awards from government, corporate and educational leaders, it has not caught the attention of SL leaders because it does not describe its cross-age tutoring program as SL, though it integrates many of SL’s principles of best practice (Honnet & Poulsen, 1989; Perren & Wurr, 2015a). Started in 1984, the program employs at-risk (defined by the program as performing at least two years below grade level) secondary students as tutors and mentors for younger learners. ‘The program has been implemented in 550 schools in the continental United States and Puerto Rico, the United Kingdom, and Brazil, benefiting almost 117,000 secondary and elementary students’ (IDRA, 2009: 4). According to the IDRA’s 2013 annual report, the tutoring program ‘has kept 98 percent of its tutors in school – more than 33,000 students, young people who were at risk of dropping out. The lives of more than 787,000 children, families, and educators have been positively impacted by the program’ (IDRA, 2013: 26).

The basic program structure provides academic credit to secondary tutors who assist younger learners in math and English. According to the program director, Dr Linda Cantu, the tutors learn these basic academic skills better while gaining self-esteem by serving as role models in school and society. The tutors have up to three tutees per year, working with them in their classes from Monday through Thursday, then completing their own reflection journals and other schoolwork on Friday.

The younger learners’ performance on standardized tests shows a clear improvement in math and English; the tutors’ test scores are not as uniformly positive, but with a 98% retention rate, success can be seen in areas as or more important than standardized test scores. One teacher I spoke with said that she had seen many tutors’ grades improve, moving from poor to honors, as a result of participating in the Coca-Cola Valued Youth program. These success stories challenge many teachers’ and administrators’ views of ‘problem students’, from ‘dropouts’ to model students and citizens:

When students are placed in responsible roles and supported in their efforts, powerful changes occur. Valued youth tutors stay in school, improve their literacy and thinking skills, develop ...