![]()

1Pathways and Backgrounds

As with any story, this one has many paths that were taken and not taken, along with backgrounds that contour the variety of possible paths, leading up to the present day. This chapter presents several of the pathways important for understanding how, when I arrived on that ferry, I found the mass of Moroccan-origin passengers who were born and raised in Europe, traveling ‘home’ for their summer holidays.

The first layer in this background relates the postwar labor migration history between Morocco and the three European nations under discussion (France, Belgium and The Netherlands). This layer accounts for the presence of Moroccans with similar, comparable migration histories in these countries. Their migration histories created material and social pathways for the annual summer holiday visit to Morocco – now, along with certain other diasporic populations in Europe (Turkish in Germany or Portuguese in France, for example), practically an institutionalized annual exodus.

This annual summer visit sets the stage for the next layer of background: multilingual practices in Morocco. Migration-based multilingual configurations are enabled by intersections of codes that are official, national and regional; written and spoken; local or foreign; and practiced in the home or outside the home by post-migrant Moroccans. All of these configurations are possible in the diasporic population, and can become relevant to practices of diasporic visitors from Europe in interaction with others in public spaces in Morocco.

The last sociolinguistic layer contextualizes how the skills involved in bargaining – an everyday activity in Morocco – are also performative utterances that change the state of the world after the speech act has been accomplished. For diasporic visitors, demonstrating bargaining skill has potential material consequences for successful or unsuccessful interactions when they try to purchase goods. These material consequences reflect on how categories of belonging in bargaining become relevant to complex global discourses of value and economic power, which feed back into the first background of migration histories between Morocco and Europe and their contemporary economic impacts in Morocco.

All together, these layers present the driving perspective on the DVs whose practices will be described in the following chapters. They frame both how and why they became participants in this project, and some of the many ‘identities’ and belongings that shape them as interlocutors with others between Europe and Morocco.

Europe and Morocco

From Europe: Backgrounds from Protectorate to Independence

Morocco experienced a short occupation period compared to other colonized states: it was only under French ‘protection’ from 1912 to 1956. Yet, the relationship between Morocco and Europe prior to the French Protectorate is long and complex, extending far beyond colonial power (see Cohen & Hahn, 1966; Minca & Wagner, 2016; Pennell, 2000, for more detail).

For Moroccan languages and diaspora, one key ideology that emerged from the Protectorate emphasizes the differences in cultural attitudes and language between Arab and Amazigh people (or Imazighen) in Morocco. Historical evidence indicates that these groups integrated their lives in a different way before colonial intervention and probably would not have taken the same pathway without it (Geertz et al., 1979). Both patterns of linguistic diversity in Morocco and patterns of out-migration from Morocco to Europe reflect how ideological differentiations separate groups within Morocco, so that those separations extend outside Morocco.

Group differentiation and integration between Imazighen and Arabs in Morocco stretch back to Islamic conquest around the 8th century, and travel through different waves of migration from the Arab Middle East to North Africa since then (Barbour, 1965; Cohen & Hahn, 1966). By the time the French arrived in North Africa in the 19th century, both groups were followers of Islam but, according to ideologies reproduced in French colonial research, the Kabyle in Algeria (a specific branch of Imazighen) were descended from Christians and were therefore more amenable to conversion to a French model of life than Arabs (Pennell, 2000: 164–166).

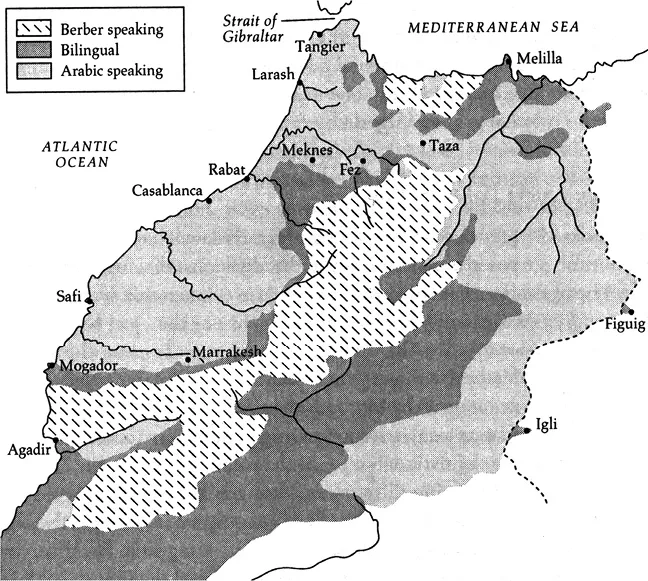

Along with this religio-cultural reputation, these groups also had distinct linguistic practices through their maintenance of the various Amazigh dialects of Morocco. As shown in Figure 1.1, these linguistic group separations stretched along the main mountain ranges of Morocco from north to south. Protectorate leaders in Morocco tried to use these linguistic differences in the same way they had in Algeria. Successive governments, both French and Spanish, attempted to Christianize Amazigh populations and integrate them into Western power structures (Pennell, 2000: 159). In fact, this attempt to divide and conquer contributed to pathways for political resistance: most revolutionary movements against French protection in Morocco emerged from the areas highlighted as Amazigh, which is still imbued with discursive legacies of resistance and rebellion in contrast to other regions.

Figure 1.1Protectorate map of linguistic diversity in Morocco

Source: (Charrad, 2001: 140, adapted from Montagne, 1973: 4).

Tendencies to rebellion under French rule created pathways differentiating Arab and Amazigh groups, which continued after the Morocco’s relatively peaceful revolution in 1956. Post-independence, predominantly during the reign of King Hassan II (1961–1999), Imazighen regions were again sources of civil unrest that resulted in government suppression. One of the more famous of these was punishing the use of Amazigh languages in public (Dalle, 2004) – symbolically a very violent way to suppress a group difference in order to build a single Arab ‘nation’ (Bourdieu, 1991).

These pathways, however, have been changing direction in recent years. Since the current king, Mohammed VI, took power in 1999, more democratic and inclusive policies have been instated which symbolically value Amazigh groups as part of the broader nation of Morocco (Howe, 2005). The Institut Royale de la Culture Amazighe (IRCAM) was created in 2001 to promote Amazigh language and culture. There are also now very public and symbolic inclusions of Amazigh identity on state-run television channels. These changes, however, arrived after a disproportionate number of Imazighen were encouraged to leave for Europe during the postwar guestworker migration period, in what was reportedly an effort by Hassan II to control this politically unruly population (de Haas, 2005a: 14).

Towards Europe: Pathways towards migration

Migration has been a nearly constant dynamic between Morocco and Europe, from before the Protectorate and beyond Independence. Throughout the Protectorate periods in the 20th century, traditional circular internal migration routes extended into other newly accessible parts of colonial France, including towards Algeria and to metropolitan France itself (de Haas, 2007). The significant movement of Moroccan populations into Europe did not begin until after Independence, in the context of bilateral labor migration contracts, through which European nations recruited ‘guestworkers’ to meet the demand of post-World War II industry.

Guestworkers were meant to fulfill short-term contracts and then return to their countries of origin. Beginning with Germany in May 1963, this sanctioned, encouraged and highly monitored migration extended to France, Belgium and The Netherlands over the next decade (Collyer, 2004: 16), finally ceasing officially in 1974. In 1965 there were about 30,000 Moroccans living in Europe; by 1975 the number had increased to an estimated 400,000 (de Haas, 2007: 46). Morocco, like many other newly independent states, looked to ‘maximis[e] emigration in order to manage unemployment levels, acquire hard currency through remittances, and raise skill levels through returning migrants’ (Baldwin-Edwards, 2005: 4).

Pathways created by migration: Connecting economies, places and generations

This short period of significant emigration has created several pathways and backgrounds which underpin the way diasporic visitors locate themselves in Morocco when they come ‘home’. One significant pathway is economic: during the guestworker migration period, while the young independent state of Morocco experienced economic and political crisis, massive recruitment plus equally strong irregular migration meant that in some areas migrant remittances became a principal form of income (de Haas, 2005b) and ‘the diaspora’ has become part of how Morocco orients towards development (Sefrioui, 2005). Certain communities have since become accustomed to remittance flows of goods and cash from migrants as part of their economic sustenance (Agoumy, 2007).

Another form of this pathway directly connects far distant places through migrants. As recruitment of workers by companies abroad had been regionally focused (de Haas, 2005a), there are now in some places narrow associations between the sending town and the destination town. The Rif Mountains, for example, have a much higher proportion of migrants who left for Belgium or The Netherlands than the Souss area around Agadir and the Anti-Atlas mountains, where France is more prominent (de Haas, 2009). Despite the linguistic and cultural connection between the former Morocco and its former ‘protector’, just as many migrating Moroccans chose Belgium, The Netherlands or Germany as their destination as chose France. As a result, there are significant numbers of Moroccan-origin communities in France, rooted in pre- and post-Protectorate migration, along with significant numbers in communities in Belgium, The Netherlands and Germany, whose inception usually dates from the guestworker migration period.

These pathways also influence a background layer about the political, economic and cultural significance of this particular flow of migration in present-day Morocco. In 1973–1974, when this legitimate means of migration was discontinued by the European nations who had invited workers, the lockdown on movement had the effect of making the trajectory permanent (de Haas, 2006: 46–47). Instead of risking returning to unemployment in Morocco without the possibility of coming back to a job in Europe, migrants began to bring their families from Morocco to settle permanently.

This transition from guestworker to economic migrant with a family – or from a temporary to a permanent diaspora – prompted new forms of interaction between then King Hassan II and his subjects. Until the 1990s, migrants were viewed by the Moroccan government as an external population that would return, and associations were set up in Europe to monitor and influence their political adherence (Belguendouz, 1999). Since 1999, Mohammed VI has put in place much broader outreach, through welcoming projects providing aid to travelers, encouraging investment by changing regulations to be more favorable towards Moroccans abroad, and building new bureaucratic outposts in the EU (Brand, 2002, 2006). An intended effect of these projects is to create more facilities for incorporating the financial and human capital of migrants into the national economy (Bekouchi, 2003; Sorensen, 2004). Although remittances are expected to fall off as migration slows and generations of Moroccan origin become integrated into other homes (Leichtman, 2002), they are nevertheless a major calculation in foreign aid received in Morocco (de Haas & Plug, 2006).

Today, Moroccans continue to migrate, both legally and illegally, into Europe, through shifting channels of entry. Legal migration from Morocco to Europe is still possible, primarily for those with social networks in an EU country, who can arrange marriages or family sponsorships. Yet even those pathways have become increasingly difficult, as EU states make parameters of allowable entry for family members more stringent. For example, in 2004 The Netherlands added a linguistic proficiency test, so that Dutch language education is now required before migration instead of after arrival, creating another barrier for potential migrants.

In recent years, primarily illegal migration through Morocco as a gateway from Africa – of Moroccan nationals as well as other African nationals – has become a major concern in policing EU borders (Alscher, 2005; Belguendouz, 2002). Because of the accessibility by water, more recent waves of illegal Moroccan migrants have arrived in Spain and Italy. Historically, these states have not had official links to Morocco to facilitate legal migration, but nevertheless they have significant Moroccan populations within their borders, often in service and agricultural industries (Bodega et al., 1995; Driessen, 1998). Moroccan migration has become a strongly contested political issue, in parallel with other nations like Turkey and Mexico whose migratory tendencies are labeled and construed as illicit (de Haas & Vezzoli, 2010). These flows and blockages of migratory movement contribute to the affective and discursive environment of negativity towards Moroccan communities in Europe, who struggle to achieve political and social stability as rightful residents in these states.

Backgrounds of diasporic communities: Stigmas of being Moroccan in Europe

Moroccan presence in Europe has evolved enormously since the waves of guestworker migrants. Much like counterpart flows of labor migrants in Europe and in North America, these families face challenges in seeking and settling into productive lives, from stereotyping and stigmatization to barriers to entry into education, housing and labor mobility (Crul & Vermeulen, 2003). A few characteristics are generalized across the political, economic and social backgrounds of Moroccan communities in the different European states where they have settled, whereas other characteristics are unique to particular states or communities.

Broadly, Moroccans are usually counted among stigmatized minority migrant groups, and are commonly subjects of negative effects of that stigmatization, including racialized and ethnicized discrimination (see Lesthaeghe, 2000; Manço, 1999; Ouali, 2004, in relation to Belgium; Césari, 2003; Guénif Souilamas, 2000; Lacoste-Dujardin, 1992; Lepoutre, 1997; Tribalat, 1995, 1996, in relation to France; Bos & Fritschy, 2006; Buitelaar, 2007; van Amersfoort & van Heelsum, 2007, in relation to The Netherlands). As post-migrant generation Moroccans are generally among the lower income residents in these places, their socialization into their communities of residence is not unlike that of other ‘working class’ groups (Willis, 1977). Place-based or locality-based identifiers are often core attributes for post-migrant generation members of the community (Césari et al., 2001; Melliani & Laroussi, 1998). In fact, as many families were settled in state-funded low-income housing, geographic ghettoization has encouraged the exaggeration of difference between the tightly bordered Moroccan community (or collectively oppressed migrant community) and outsiders to it (Lepoutre, 1997; Silverstein, 2004). Religious difference also plays an increasingly important role in the insulation of the predominantly Muslim community (Bistolfi & Zabbal, 1995; Césari, 1994; Maréchal et al., 2003; Sayyid, 2000) from the predominantly Christian hegemony that crosses national borders in Europe.

Some differences in Moroccan communities from state to state are due to particular structures of governance and political activity in each place. For example, the majority of individuals identifying as ‘Moroccan’ can also claim Moroccan citizenship, which is passed genealogically, regardless of place of birth. Yet because of variations in systems of nationality and citizenship in different European states, and over successive political movements, there is no uniform model of official national identity for post-migrant generation Moroccans. Some obtained citizenship in the European state at birth, some at age of majority and some not at all, depending on their parents’ status, their year of birth ...