![]()

1Introduction

Tourism cannot be explained unless we understand man, the human being

Przeclawski, 1996: 239

Introduction

This chapter discusses the background behind the tendency of tourism researchers to examine impacts as the traditional root of ethical issues in tourism. The chapter also analyses alternative tourism and sustainable tourism paradigms as the field’s most frequently used means by which to alleviate the negative impacts of the industry. A brief summary of work on tourism and ethics provides a generalised snapshot of the range of studies undertaken to date in addressing ethical issues in tourism. The chapter further discusses the negative backlash that has come about regarding the so-called ‘new tourism’, and sets the stage for the discussion in later chapters on human nature and ethics, and how these relate more specifically to tourism.

Tourism Impacts

One of the longest-standing traditions in tourism research, which is almost universal in our books and academic papers, is the necessity of discussing at the outset the idea that tourism is the world’s foremost economic engine. This is natural from at least two perspectives. The first is that it seems to legitimise the importance of tourism through an approximation of its overall magnitude regarding foreign receipts, employment and other such indicators. Second, it demonstrates that, apart from its position as the formidable economic giant, there are associated costs, which have been discussed almost universally as sociocultural, economic and ecological impacts.

The concern over tourism impacts originates from the 1950s, when the International Union of Official Travel Organizations’ (the precursor to the WTO) Commission for Travel Development first initiated discussions on how to minimise destinational impacts (Shackleford, 1985). During the 1960s, publications such as National Geographic and Geography picked up on the negative impacts from tourism in places that were at the leading edge of the mass tourism phenomenon, including Acapulco (Cerruti, 1964) and the Balearic Islands, Spain (Naylon, 1967). The pace of international tourism intensified during the 1970s, and impacts were discovered in many more of the sea, sun, sand and sex destinations, such as Gozo (Jones, 1972), as well as in city environments, including London, where Harrington (1971) observed how unregulated hotel development led to a lower quality of life. Tourism research on impacts hit its stride during the 1970s on the strength of work from scholars such as Budowski (1976), whose classic paper on the interactions between tourism and environmental conservation were explained as: (1) conflict; (2) coexistence; or (3) symbiosis. In the majority of cases he felt that the relationship was one of coexistence, moving towards conflict. Such were the conclusions of other esteemed authors, who felt that poorly planned tourism development had many serious effects on the integrity of the natural world (Cohen, 1978; Krippendorf, 1977).

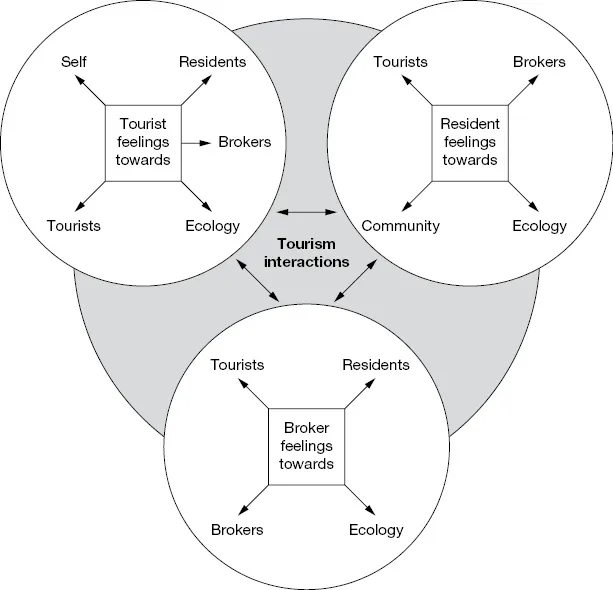

The conflict so often identified by these and many other successive papers is no more clearly articulated than in the following case study on tourism impacts in Goa, India (see Box 1.1). The maturity of the tourism product in Goa has created a level of competition and fractioning within society that is extreme – conflict in the words of Budowski (see the work of Lea, 1993, who discusses both the impacts of tourism on Goa as well as the beginnings of responsible tourism). This fact has been supported by literally dozens of academic reports, which identify the polarisation of socioeconomic conditions, usually between the lesser developed countries and the most developed countries, leading to a number of interaction problems between tourists and resentful hosts (see, for example, Ahmed et al., 1994). The intersection of many competing interests from a number of different stakeholder groups frames the basis for the impacts that we experience in tourism. The main groups involved in these interactions include tourists, inhabitants of the destination and tourism brokers, as illustrated in Figure 1.1 (Fennell & Przeclawski, 2003). The combinations of these interactions are extensive, and include: (1) the tourist’s own personal or existential experiences, and interactions with other tourists, residents of the destination, tourism brokers and the ecology of the region; (2) residents’ interactions with tourists, brokers, the community in general and ecology; and (3) brokers’ interactions with tourists, residents, other brokers and the natural world. These interactions range along a continuum from negative (hostile) to positive (symbiotic), as noted above, and are moderated by time, space, situational factors, resource allocation and a whole host of other elements.

Box 1.1 Tourism impacts in Goa

India’s smallest state, Goa, is indicative of the extent to which tourism can transform a region. Noronha examined over 50 newspaper articles from just 1995 to 1997, documenting much of the uneasiness that tourism has created in the region, which was identified as problematic 10 years earlier when German tourists were pelted with cow dung on their arrival. A decade later, articles were suggesting the following: land values had skyrocketed due to tourism; very few of the lush green hills that once were prevalent remain; agricultural land has been lost to tourism development; government officials have been targeted through allegations of misappropriation and corruption in the name of tourism; building regulations have been violated, especially by the large hotels; no proper scientific or economic assessments have been undertaken to plan tourism; no priorities have been established; rapid urbanisation has transformed the region; age-old storm water drains have been turned into sewage conduits; the beach plays host to drug dealers whom the police turn a blind eye to; folk art has been eroded with great loss to authenticity; water shortages and electricity shortages have occurred because of the demand placed on the infrastructure from large hotels; waste disposal systems are overrun; transport systems are inadequate; the water pipeline meant for locals has been taken over by hotels; tourists on several occasions have been beaten up by villagers; strong-armed tactics (gangsters) have been used to displace local people for the development of hotels; local residents have protested plans to have hawking zones established in certain areas; beach shacks and temporary restaurants have been shut down by authorities, because they charge lower prices than the hotels; beaches are overly crowded; hotels often do not pay staff for up to three months, because of their own slim margins; the cost of living for locals has gone up markedly; apartment blocks are turned into makeshift hotels, which undercut the cost of rooms in hotels; child sex abuse is rampant; AIDS is becoming a problem; paedophiles have been identified in Goa; the police have been known to extort money and frame people on drug-related charges; tourists have been raped; the density of hotel establishments per km in some areas is excessive (43 establishments per km); firms have pushed local authorities to privatise Goa’s old and historic forts; politicians push for more tourism as visitation begins to fall; scarcely 10% of Goans have benefited from tourism; beaches that cater to up to 10,000 per day remain without toilets; and malaria is spreading throughout Goa. Given the magnitude of the problem in Goa, it is easy to see how mismanagement and greed have dictated the levels of growth in this region.

Source: Noronha (1999).

Figure 1.1 Tourism interactions

Source: Fennell and Przeclawski (2003).

Alternative tourism (AT) and sustainable tourism (ST)

It is not the purpose of this section to fully elaborate on the development and impact of AT and ST, which can be found in many recent tourism publications, but rather to briefly provide an historical context that emphasises certain paradigmatic changes in tourism that were borne out of efforts to both understand and mitigate tourism impacts, and thus to implicitly strive to become ethical.

The intensity of moral concern in tourism intensified during the late 1970s and early 1980s through the AT paradigm, which emerged through its potency in providing an alternative to mass tourism. The tenets of the ecodevelopment paradigm of the 1970s, including enlarging the capacity of individuals, self-sufficiency of communities, and social and environmental justice, were articulated through AT, which was meant to be both a softer and gentler form of tourism (Riddell, 1981; Weaver, 1998). This meant that ‘small scale’ was thus better than ‘large scale’; locally oriented was better than externally oriented; low impact better still than high impact. These polarised options where recognised early in the work of Dernoi, who observed that AT would: (1) provide economic benefits for individuals and families (e.g. through accommodation provision); (2) allow the local community as a whole to benefit; (3) allow the host country to benefit through the avoidance of leakages and the reduction of social tensions; (4) provide an option for cost-conscious travellers coming from the ‘north’; and (5) realise cultural and international benefits across countries and continents (Dernoi, 1981).

There is little question that AT provided a needed backdrop from which to gain perspective on the often disingenuous side of mass tourism. However, the dichotomous positions that are inherent in the mass-alternative perspectives are rarely encountered in their purest forms because of the sheer complexity of different attractions, accommodations, transportation and facilities that the traveller encounters on a day-to-day basis (thus minimising the true alternative nature of the trip) (Weaver, 1998). This was identified early by Butler, who quite effectively observed that, while mass tourism has a callous side, it may be just as destructive to promote AT without being confident of what it can achieve for the community, socially, environmentally and economically (Butler, 1990). This sentiment has led theorists to conclude that it is perhaps best to view AT not as a replacement for mass tourism (this will surely never take place), but rather as a model in helping to amend some of the problems that are inherent in mass tourism (Butler, 1990; Cohen, 1987). So where AT is perhaps most beneficial is in defining the range of the continuum regarding tourism development. And as development economists might suggest, it is perhaps better to have a balanced approach to development within a region, including a number of active sectors in the economy for the purpose of achieving balanced growth, including mass tourism and AT.

Alternative tourism articulated many of the tenets supported by the sustainable development (SD) platform, which emerged late in the 1980s. SD subsumed ecodevelopment, but also intensified at a broader scale in its application to poverty, limits on technology and unfettered growth, cross-cultural applications, its ability to be integrative, and its use at broader scales (Redclift, 1987). For tourism this meant that if the industry was to become sustainable, it would do so by adhering to a number of basic principles, including: (1) reduction of tension between stakeholders; (2) long-term viability and quality of resources; (3) limits to growth; (4) the value of tourism as a form of development; and (5) visitor satisfaction (Bramwell & Lane, 1993), and through the realisation that ST is a process and an ethic (Fennell, 2002). The need to articulate such criteria in ST is underscored by González Bernáldez, who notes that benefits and costs must be weighed equally in a better understanding of the impacts of tourism, as follows (González Bernáldez, 1994):

Benefits

•Increases and complements financial income.

•Improves facilities and infrastructures.

•Allows greater investment for the preservation of natural and cultural enclaves.

•Avoids or stabilises emigration of the local population.

•Makes tourists and local populations aware of the need to protect the environment and cultural and social values.

•Raises the sociocultural level of the local population.

•Facilitates the commercialisation of local products and quality.

•Allows for the exchange of ideas, customs and ways of life.

Costs

•Increases the consumption of resources and can, in the case of mass tourism, exhaust them.

•Takes up space and destroys the countryside by creating new infrastructure and buildings.

•Increases waste and litter production.

•Upsets natural ecosystems, and introduces exotic species of animals and plants.

•Leads to population movement towards areas of tourist concentration.

•Encourages purchase of souvenirs that are sometimes rare natural elements.

•Leads to a loss of traditional values and a uniformity of cultures.

•Increases prices and the local population loses ownership of land, houses, trade and services.

But how is it that we determine what is a tourism benefit and what is a cost? To whom, and at what scale? McKercher (1999) has noted that the most unfortunate reality confronting tourism is that its plans and models have been mostly ineffective at controlling the adverse effects of the tourism industry. If traditional models explained tourism fully, he suggests, then they would also be able to offer insights into how best to control such impacts. Traditional models in tourism are ineffective because they imply strongly that: (1) tourism can be controlled; (2) its players are formally coordinated; (3) it is organised easily in a top-down fashion; (4) service providers achieve common, mutually agreed-upon goals; (5) it is the sum of its parts; and (6) an understanding of each of these parts will allow us to understand the whole. Therefore, by nature, tourism is far too complex to be explained by linear, deterministic models. This presumably includes sustainable tourism too. So, if ST is more about development than conservation, it is because the former reflects more of who we are and what we represent. We can demand from science all we want regarding a more ecocentric lifestyle. It does not mean that change will be easily attained or socially desired, despite the new morality that has emerged regarding more ethical attitudes about a number of different social and ecological issues (Fox & DeMarco, 1986).

What has come about, along with AT and ST, to a...