![]()

Chapter 1

In the middle of things: city, cinema and the public sphere

The photograph Le Reflet from the photo series Périphérique by Mohamed Bourouissa (2007, Figure 1) shows old computer monitors and TV sets stacked on top of each other on a low concrete base amid a suburban housing area. At the front edge of the pile but somehow also part of it, there is a human figure in a light-coloured tracksuit sitting on an upturned monitor with his back towards us. He is leaning slightly forward and gazing into the pile. Even if the ensemble of the monitors and the figure seem to be carefully cast, the whole scene gives the impression of a garbage site. The human figure could be an inhabitant of one of the tower blocks of his surroundings, yet his soft, roundish forms and his self-absorption also make him seem like an estranged element in the arrangement. We only see the back of the person and a pronounced unisex outfit, but the broad shoulders and the open position of the legs suggest that the person amid the pile of monitors is a man – probably young or middle-aged since old people usually do not go around in tracksuits like the one depicted here.

This image poses the question of how to create connectivity in contemporary living areas that are heavily interspersed with mass media. In addition, it links this question to a contemporary urban scene that seems to transcend national boundaries. Because even if the series title Périphérique suggests that the photograph was probably taken in one of the French banlieus, it could in fact also have been shot in parts of Berlin, Vienna, Warsaw or Novi Sad.

Furthermore, various other questions concerning our contemporary urban dwelling condition also come up. For instance, how can public connectivity be created in an environment in which individuals are increasingly thrown back onto themselves, in which one can no longer hark back to the lines of tradition and convention handed on from birth in order to make sense of things and in which affiliations usually change quickly and often? Then there is the question of how to deal with the fact that urban landscapes are increasingly segregated nowadays: there are dormitory suburbs, such as the one depicted in the photograph, as well as office areas and amusement miles. The superposition of various functions in one place, which Richard Sennett (2003: 297) presented as an important precondition for the emergence of a public sphere, is often missing.

At the same time the photograph also highlights the importance media channels assume in such segregated urban environments. These channels are detached from the local setting and at the same time offer a stream of globally organized images and information. One can enter this stream any time in order to find quickly changing material for identification and for a confrontation about sense and belonging – which tends to be expressed in the form of direct action (or inaction) and is no longer re-inserted into complicated procedures of (public) representation (Hobsbawm 2007: 106).

Figure 1: Le Reflet from the series Périphérique, Mohamed Bourouissa, 2007–2008 © Mohamed Bourouissa, courtesy the artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris.

Hence, the question arises as to the transnational and global processes that are becoming dominant today and are replacing the older national ones in providing the frame of reference for today’s acting and perceiving. Connected to this, we are also confronted with the loss of attractiveness of classical ‘modern’ institutionalized arenas for creating a public sphere, for example associations, unions, clubs, parties or state-run institutions. What again suggests a corresponding tendency: the importance that cultural phenomena acquire in a struggle over the shape of the common world. This involves new media, film, Internet, music, fashion or sports, and the highly media-dependent arenas connected with them – such as cinemas, multimedia or party spaces, concert halls or stadiums. And in turn, this points to the fact that the struggle about a visible presence of cultural difference is increasingly appearing alongside those about social equality and the redistribution of wealth.

Le Reflet by Mohamed Bourouissa draws attention to the relation of the individual vis-à-vis the global flow of images. It highlights the alienating and isolating dimensions of these changes in contemporary city landscapes. In order not to fall into the trap of narrating a mere history of decay in respect to these transformations, I will confront this photograph with another artwork that exposes and interrogates the community-creating force linked to contemporary media and the role of cinema in constructing a public sphere in particular.

1.1. Cinema’s potential for creating a public sphere

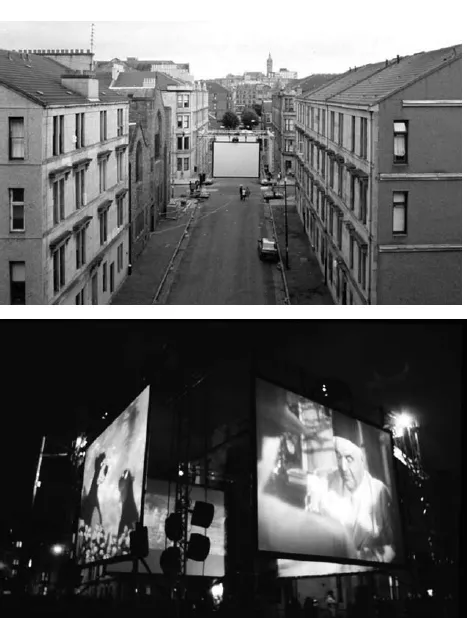

The Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija created the installation Community cinema for a quiet intersection (against Oldenburg) as part of the City of Architecture Festival in Glasgow, Scotland, in September 1999 (Figure 2a–b). He created a temporary outdoor cinema composed of four screens and accompanied by a Thai café right on a traffic intersection in a residential neighbourhood in Glasgow and after dusk showed films that had been chosen by the local community: Casablanca, A Bug’s Life, The Jungle Book and It’s a Wonderful Life were shown in parallel on the four screens.

Figure 2a–b: Community cinema for a quiet intersection (against Oldenburg), Rirkrit Tiravanija, installation at the City of Architecture Festival in Glasgow, Scotland, September 1999 © Rirkrit Tiravanija, courtesy The Modern Institute, Glasgow.

This installation accommodated various references: to open-air cinema or drive-in cinemas, to ciné clubs and community cinemas, but also to management strategies of the Hollywood film industry and multiplex cinemas as well as to newly invented, local ‘traditions’. The most striking of these references is that of community cinemas and open-air cinemas.

Already in its title, but also with the amateur-like conglomerate of screens, street kitchen and loosely distributed seats, the installation quotes the practice now widespread in many countries of setting up cinema situations using a bare minimum of equipment, such as easily erectable screens, portable projectors, simple chairs, sometimes accompanied also by a street kitchen or a drinks trolley. In connection with the attractor film, this setting can encourage people to gather in the most diverse – sometimes also very poor and difficult to live-in surroundings1 – whereby the collective body formed in this way somehow always alters the standard cinema setting. Hence the situation created by Tiravanija is aimed at creating a connectivity among neighbours as well as strangers, and at the same time it stages a difference by bringing a Thai café and Hollywood classics together, which gave it a rather exotic touch in the Glasgow neighbourhood.

In addition, the four screens high above the intersection recall drive-in cinemas and the public survey that was realized in order to determine which films should be shown on the screen recalls production strategies of the Hollywood film industry and of the multiplex cinema, which since the 1980s have sought to integrate ‘all of us’ and to offend or exclude nobody.2 Last but not least, there is a connection to ‘Thai’ traditions that is kept vivid not only by the setting up of a Thai café, but also by information circulated by the artist himself. In a short e-mail exchange, Tiravanija mentioned that one of the inspirational sources of this work are outdoor cinemas in Thailand, which are set up as part of temple festivals, or nearby Chinese shrines where the film is offered to the gods or goddesses (of the shrines) to thank them for the fulfilment of a wish.3 With this mix of associative references, the cinema installation presents itself as a cross between bottom-up activism, commercial and religious operations and local and global procedures.

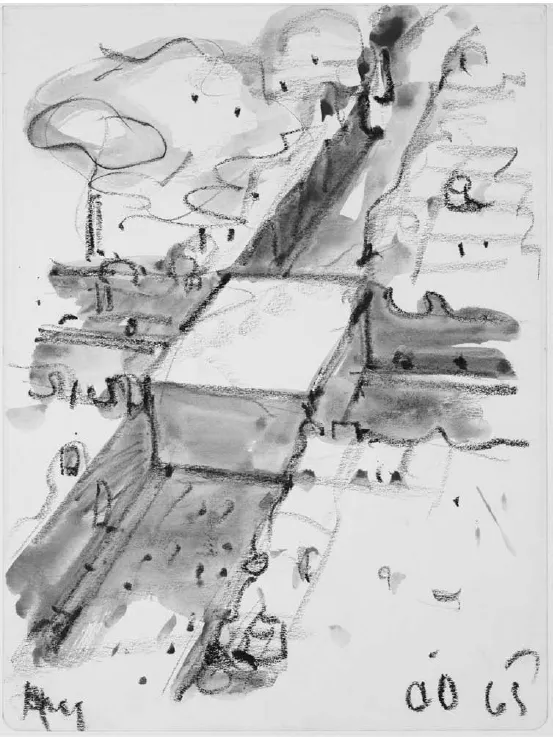

At the same time, Community cinema for a quiet intersection not only relates explicitly and implicitly to other contemporary cinema phenomena on a local as well as global scale but also distances itself actively from certain traditions – most notably from those rooted in the classical modernist art world. The subtitle of the installation is ‘Against Claes Oldenburg’. Accordingly, part of the information that Tiravanija himself circulates about this urban intervention is a drawing (Figure 3) in which the American artist Claes Oldenburg drafts a protest installation against the Vietnam War.4 In sketching a big cube occupying the intersection of Canal Street and Broadway in New York City (1965), a Block of Concrete with the Names of War Heroes, Oldenburg staged his intervention as a kind of provocative obstacle for city dwellers. In doing so, the artist drew on the convention of ‘irritating’ and ‘awakening’ the public and of stimulating viewers to reflect on existing attitudes.

Figure 3: Proposed monument for the intersection of Canal Street and Broadway, N. Y. C. – block of concrete with the names of war heroes, Claes Oldenburg, 1965 © Claes Oldenburg, 1965, courtesy digital image: New York, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)/Scala Florence.

By quoting Oldenburg explicitly, but by deploying at the same time a much less hierarchical relationship between artist and public, Tiravanija’s installation distances itself from this convention and in this way highlights the innovative and anti-modernist character of his alteration. Community cinema for a quiet intersection not only stages the fact that it is meant to be used in order to constitute a community, but the installation is even presented as responding to choices made by the public. As already mentioned, the films shown on the four screens were determined by a survey conducted in the neighbourhood – similar to those made by sales departments of production companies, by media or the public sector. However, through the brusque, montage-like arrangement of the four screens directly above the traffic intersection and the achieved interruption of everyday traffic flow that this creates, the installation presents at the same time an unusual and uncomfortable solution – one that challenges our ability to make sense inside urban environments that, because of the above-mentioned tendencies towards segregation, are often too poorly adapted to create a shared public sphere.

Tiravanija’s temporary urban intervention thus shows a strong contrariness, it offers involvement and at the same time reflective dissociation, which makes it difficult to inhabit it and to create the very connectivity that it seems to be designed for. Correspondingly, photographs of the screening show the setting being rather loosely populated by visitors mostly individually absorbed in the performance on the screen. This contrariness, however, is also able to stimulate an (ad hoc or retrospective) observation and reflection of the function that the cinema has in creating a public sphere, a function that, as I will show in the following chapters, persists despite the dissemination of new media such as TV and the Internet. To put it another way, there seems to be a potential for creating a public sphere inherent in the cinema setting that is responsible for its persistence in the age of video, TV, Internet and digital media since this somehow counteracts the further ‘privatization’ and ‘fragmentation’ of the political that goes along with these new media – and Tiravija’s community cinema invites us to examine this.

As Georg Simmel (1997) has pointed out, there is a power of cinema in respect to socialization that is related to the particular and strongly standardized arrangement of space, light and bodies that characterizes the cinema setting. What we usually understand by ‘cinema’ is either a space marked off by four walls or an outdoor situation that uses barriers to somehow simulate this. On one of these walls we find an enormous screen that can be covered by curtains. On the opposite side – even if in most cases behind some further covering, and so invisible to the viewer – we find the film projection machinery and the projectionist. In between there are a great many numbered seats, in orderly, narrow rows, all facing one direction: towards the screen. Already the size of the space and the physical closeness between the people in the seats can create an exciting effect, an impulsiveness and a sweeping-away of the public, which enhances the feeling of being part of a collective. In addition, the darkness of the cinema space creates an uncertainty of the spatial frame, which further amplifies these effects. In the cinema we are huddled together with those next to us in a pronounced bodily way, and at the same time the boundaries of the space as a whole disappear and allow fantasy to expand it towards infinite dimensions.

In Community cinema for a quiet intersection this familiar setting is quoted and at the same time rearranged. We have four screens instead of one and they are placed in the middle rather than at the side. Consequently, the space around the four screens is in no way confined and can, theoretically, be endlessly expanded as the audience grows. There are no fixed seats but people can stay or sit wherever they choose and are challenged to watch the films, but also to make sense of the unusual situation they find themselves in. This way the situation turns into a ‘cinema to think with’. At the same time there is still darkness, a gathering of people from the neighbourhood mixing with strangers related to a screen, and a physical excitement responding to the presence of others and the exposition of the film.

As will become clearer in connection with further examples we will encounter in this book, there is a standardization of the cinema setting that is so well anchored in habit and collective memory that it remains somehow present even if it is as drastically rearranged as in this example. A further effect of this standardization is that cinema generates a familiar feeling even if one enters a place one has never visited before – which, however, not only has to do with the consistently similar organization of space but also with the information available about films being shown. In cinemas in bigger cities in quite different countries there is usually some place where one can see a recent film one has heard or read about even if there are major differences between various cinema worlds in terms of regional, global or genre attribution (for instance: Bollywood, Hollywood or European art house cinema). Cinemas thus also function as temporary, familiar shelters even in places one is living in as a stranger on a business trip, as a tourist or as a migrant. And it is this strange familiarity of cinema that Tiravanija evokes and brusquely combines with the anonymity of an urban intersection.

Interventions in contentious territories

Tiravanija’s installation combines two situations that usually do not belong together: the cinema and a traffic intersection, and in this way he alienates them and turns the situations he creates into a riddle. Cinema is transformed into a work of art, however, into one that strongly interlinks with the various elements and agents that already exist in the place it has been created for: the intersection and a local flow of traffic in a Glasgow neighbourhood, an international art discourse, a canon of classical movies, management strategies concerning the dissemination of movies or people’s personal choices concerning film.

Every attempt at setting up a cinema intervenes in a similar way into what is already present in a situation. But a still dominant idea of space being created by architects and urban planners and only afterwards populated by people conceals this. The riddle-effect that goes together with this art installation points to the fact that cinema is always already an intervention into a space that in itself is shaped, perceived and loaded with feelings by various agents. Tiravanija’s installation thus is able to serve as a starting point for presenting and clarifying key concepts used in the present study such as ‘social space’, ‘contentious terrain’ and ‘public sphere’.

Why is the spatial dimension singled out in this way as one being particularly important to the investigation carried out in this book? First of all, because cinema is, as we have seen, primarily a spatial connection emerging between a simple architectural box, a multitude of bodies brought physically close to each other, darkness and a film shown on an enormous screen – whereby the darkness allows fantasy to expand space almost infinitely. Roland Barthes, for instance, writes that when he says ‘cinema’, he imagines ‘hall’ and not ‘film’ and further defines this setting as being a dark, anonymous cube, where a celebration of affects, called ‘film’, is capable of taking place (Barthes 1975).

The importance of space, furthermore, comes up in connection with cinema activism in particular. In 2004, during the research process for a previous book (Schober 2009b), I frequented an urban space in Belgrade, the Cinema Rex, which had an important function in public and urban life in the 1990s.5 It served as a haven but also as a connecting and motivating factor for various oppositional movements against the Milošević regime. Although the architecture resembles an old, perhaps art deco cinema hall, the Cinema Rex was never really a cinema. It was built as a Jewish cultural centre in the early twentieth century, and later became a location for several activities of the Communist Party and its sub-organizations. Only in the 1980s was it ‘dressed up’ as a cinema in the course of a film shoot, and after this it was adapted as a cultural centre by various cultural and political groups. For example, Low-Fi Video activists, whose procedures I will present later on in more detail, constituted themselves in this space and drew their first audience from people who were already connected to the Cinema Rex in one w...