eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Manifesto Now!

Instructions for Performance, Philosophy, Politics

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Manifesto Now!

Instructions for Performance, Philosophy, Politics

About this book

Manifesto Now! maps the current rebirth of the manifesto as it appears at the crossroads of philosophy, performance and politics. While the manifesto has been central to histories of modernity and modernism, the editors contend that its contemporary resurgence demands a renewed interrogation of its form, its content and its uses. Featuring contributions from trailblazing artists, scholars and activists currently working in the United States, the United Kingdom and Finland, this volume will be indispensable to scholars across the disciplines. Filled with examples of manifestos and critical thinking about manifestos, it contains a wide variety of critical methodologies that students can analyse, deconstruct and emulate.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Manifesto Now! by Laura Cull, Will Daddario, Laura Cull,Will Daddario in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Politica pubblica in ambito scientifico e tecnologico. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Analogue 1

Absent Futures: The Ironic Manifesto in an Age of Austerity

Since the fall of 2009, universities throughout California have been flooded by protests against the state government’s massive cuts to public education. Collective and direct actions across the state have taken a variety of forms: from rallies and encampments to building occupations and highway blockades. Participants and commentators alike have linked these protests to the ‘new student rebellions’ that are a crucial part of the anti-austerity resistance growing worldwide (Solomon and Palmieri 2011).1

Protests at Californian universities were first sparked when students, faculty, and workers of the nine campuses that make up the University of California (UC) system returned from their summer breaks in 2009 to find a university strikingly different from the one they left the previous spring. Classes that students had hoped to take or needed to graduate had been cut. Classmates who could not afford the 32 per cent fee hike instituted that year would shortly have to leave the university (Gordon and Khan 2009). They were accompanied by thousands of workers and support staff at the UC, laid off as part of the administration’s drastic austerity cuts. Other cuts included furloughing employees, gutting unprofitable programmes, decreasing faculty wages, and ending good-faith negotiations with labour unions (Lye and Newfield 2011). The UC Office of the President and the UC Board of Regents justified these measures by declaring an ‘extreme financial emergency’, caused by the state’s slashed funding for public education (UC Board of Regents 2009).

While the extraordinary measures taken by the UC administration in 2009 were certainly triggered by the onset of the financial crisis in 2008 and the ensuing state budget deficit, their determining conditions were laid decades earlier. In 1978, the passage of Proposition 13 set in motion a trend that curtailed public sector funding in California by capping taxes on corporate and private property. In the 30 years since, this legislation has made it effectively impossible for California to raise the revenue needed to support its public infrastructure and services. This has prompted the accelerating trend of privatizing California’s once formidable public sector. The Terminator-like cuts to public education pushed through by former Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2009 were not isolated. Nor were they anything new; the defunding of public higher education in the state of California was the escalation of a tendency toward privatization in full swing since at least the 1970s.2 In short, the ‘emergency’ facing the UC in 2009 (which it continues to face) was an increasingly familiar and normalized symptom of neoliberalism coming home to roost. Once reserved for nations saddled with obligatory structural adjustment programmes, mandated by the International Monetary Fund, austerity is swiftly becoming a defining condition of social life worldwide – the flip side to privatization on the neoliberal coin.

While the 2009 cuts to public higher education were nothing qualitatively new, the wave of resistance that accompanied them was. The first coordinated day of action across the UC system took place on 24 September 2009, coinciding with the start of the academic year at most of the UC campuses. The largest protests that day erupted at UC Berkeley, where 5,000 people walked out of their classes and jobs to take part in a massive campus rally, march, and sit-in. This would be just the beginning of a year marked by what Colleen Lye and Chris Newfield call ‘the largest and most widespread campus-based actions in the United States since the 1960s’ (Lye and Newfield 2011, p. 59).3

Accompanying this flood of actions was a wave of documents whose authors articulated an array of ideological positions on, and possibilities for, intervening into the cuts. While some urged for legislative reforms to restore funding to the UC, others called on activists ‘to push the university struggle to its limits’, with an eye to radicalizing campus resistance and linking it to struggles emerging beyond the university (Research and Destroy 2011).4 Amidst the voices, none raised more eyebrows than a group calling itself the UC Movement for Efficient Privatization (UCMeP).

A week before the 24 September day of action, UCMeP circulated ‘a manifesto for privatization’ online and in a Bay Area newspaper. In ‘Privatize Now! Ask Questions Later’, UCMeP claimed to share the concerns of others over ‘the pending privatization of the world’s premiere public university’ (2009). They made certain to distinguish themselves, however, from ‘the thousands of faculty, staff, and students whining over the direction of privatization’ by expressing impatience over ‘the snail’s pace at which this inevitable transformation [toward privatization] is proceeding’. After positing numerous demands they claimed would help the UC overcome its ‘fiscally reckless’ goal of pursuing excellence in public education, UCMeP resolved to take direct action to help dismantle one of the world’s premiere public higher education systems.

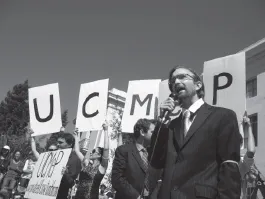

Figure 1: UCMeP auctions off UC Berkeley campus landmarks to the highest bidder during the student walk-out on September 24, 2009. Credit: Anders Sundnes Løvlie.

UCMeP followed through on its pledge just a week later when, on 24 September, eleven suit-clad members of UCMeP stormed the 5,000-person rally at UC Berkeley. The militantly-neoliberal rhetoric of their speeches and posters (which bore messages like ‘Diversify Your Portfolio, Not the Student Body!’ and ‘Public Education = Communist Putsch’) elicited a mix of boos and knowing laughter from the massive crowd gathered that day on Sproul Plaza, the birthplace of the 1960s’ Free Speech Movement. The ambivalent mood soon abated when UCMeP’s spokesperson announced:

As we all know, President Yudof, the UC Board of Regents, and the state legislature have been working tirelessly and getting paid top dollar to sell off the UC’s worldwide reputation of providing excellence in public education. To help make this process more efficient and swift, UCMeP is taking direct action by auctioning off key campus landmarks to the highest bidder!

The joke quickly landed as placards spelling out U-C-M-e-P (pronounced ‘You See Me Pee’) were flipped to reveal giant ‘Monopoly’ cards, each one a deed for a different campus landmark. In the ensuing auction, students, faculty, and staff scrambled to buy their favourite piece of property for fire-sale prices. As the auction concluded with Sproul Plaza selling for a bargain $2.35, one student grabbed the microphone to declare loudly: ‘This is not a joke! This is what is happening to our university!’5

UCMeP was founded in early September 2009 by a small group of graduate students and alumni at UC Berkeley, myself included. Since then, it has developed a satiric and performance-based repertoire of contention inspired by contemporary activist performance groups like the Yes Men and the Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army.6 UCMeP’s humorous interventions have included a mix of satiric manifestos and memorandums, elaborate online hoaxes, and sardonic public performances that take the logic of the UC administration to its absurd extreme. UCMeP operates through playful yet earnest performative manipulations of the authoritative discourses used by the UC administration to legitimate everything from tuition increases to the criminalization of student activism.7 With its impatience to act and uncompromising ideological position, the UCMeP-issued manifesto corresponded closely to key conventions of the manifesto genre. Yet the striking dissimulative seriousness of ‘Privatize Now! Ask Questions Later’ jarred dramatically with the gravitas that typically defines the manifesto.

In what follows, I approach UCMeP’s ironic manifesto as an occasion for examining how irony might give the manifesto particular political efficacy in an age of austerity. Of interest here is not only the use of irony in the manifesto but manifestos that are themselves defined by the tropological radicalness of irony. The ironic manifesto, as discussed here, is not a parody or imitation of the manifesto. Its ‘irony’ indicates a particular way of functioning. The ironic manifesto does not constitute a genre; it is a form of the manifesto. As such, the ironic manifesto performs a particular function, which makes it distinct from other manifesto forms. My methodological decision to focus on a document produced by a group I have actively participated in for over three years should certainly raise questions regarding the objectivity of my analysis. I hope my intimate knowledge of this particular manifesto, and the context into which it sought to intervene, can evidence, if not the efficacy of the ironic manifesto, then certainly the hopes behind it.

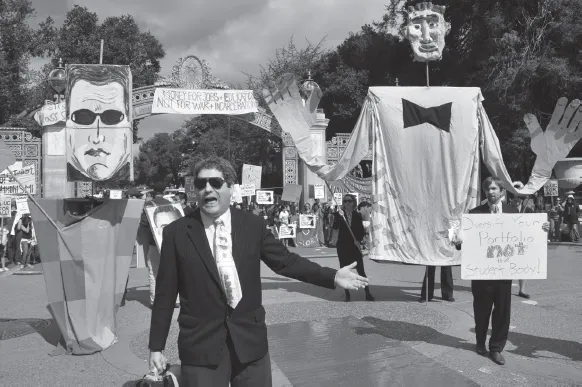

Figure 2: UCMeP rolls out the red carpet for students to cross the picket line in March, 2010. Credit: Benjamin Kieswetter.

Irony and the Manifesto

To speak of irony and the manifesto together is – theoretically at least – an endeavour filled with difficulties, not the least of which is the ontological uncertainty inherent to both terms. Often taken to be earnest, heady, if not a bit heavy-handed, the directness of the manifesto seems antithetical to irony’s duplicity. In her landmark study of the manifesto, Janet Lyon explains that the manifesto’s capacity for rhetorical trompe l’oeil tends to shape its wide intelligibility: the syntax of a manifesto is so narrowly controlled by exhortation, its style so insistently unmeditated, that it appears to say only what it means, and to mean only what it says. (Lyon 1999, p. 9)

This description of the manifesto stands in stark contrast to the common definition of irony as saying one thing while meaning another. Such ontological tensions, however, hardly indicate a mutual exclusivity between the manifesto and irony. There is nothing about the manifesto as a genre that precludes its synthesis with irony’s rhetorical and tropological radicalness.8 Instead of speculating on the very possibility of syncretizing irony and the manifesto, this essay focuses on the possibilities that inhere in such a syncretism. I am interested in the common ground shared by irony and the manifesto, particularly the potentially constructive but more often disruptive role both play in the making and unmaking of the public sphere, not to mention the counterpublics by whom and for whom manifestos are typically produced (See Warner 2002).

For Lyon, the relation of the manifesto to public discourse is clear: ‘The manifesto as a genre is constitutive of the public sphere to the degree that it persistently registers the contradictions within modern political life’ (1999, p. 8). She explains that manifestos can articulate group identity and establish speaking positions for subaltern groups, albeit with an impatience that violates the assumed decorum and ‘gradualist language of debate and reform’ characteristic of the liberal public sphere (p. 31).9 She attributes tremendous agency to the manifesto and asserts that although the manifesto ‘circulates through and is intelligible via the discourses of modernity…it is more than merely a ‘discourse’ in the post-Marxist sense of that term. It carries an incipient threat of action against the democratic state by groups who have little to lose from the state’s disruption and even dissolution’ (pp. 33–4). For Lyon, the manifesto can help make visible identities and ideas that were previously hidden from view, all while upsetting the smooth and homogenous functioning of the public sphere.

Irony, too, is widely embraced for its crucial presence in the public sphere, especially in late liberal societies. In a recent study, Dominic Boyer and Alexei Yurchak note how ‘increasingly commonplace’ ironic and parodic forms of engagement have become ‘in late-liberal political and public culture’, particularly in public interventions from the left (2010, p. 191). As evidence they offer a number of examples in US society since the late 1990s, including popular cultural figures such as Stephen Colbert and Jon Stewart as well as activist performance groups like the Yes Men and Reverend Billy. According to Boyer and Yurchak, each of these figures utilizes a similar methodology that relies on parodic over-identification with the predictable forms of authoritative discourse in media and political culture. Such ironic interventionist strategies, they argue, succeed in confounding the ‘authoritative discourse’ that is used in the late liberal public sphere to manufacture consent and shore up sites of disagreement and contradiction (2010, p. 212).

Ambivalence towards, and the ability to disrupt, public discourse in the public sphere is certainly not the only ground that the manifesto and irony share today, or even historically. Any discussion of irony cannot ignore what Linda Hutcheon has described as its ‘transideological nature’ (1995, p. 10). Likewise, we cannot ignore the wildly different projects in which the manifesto has been complicit. Nonetheless, what follows examines how a syncretism of irony and the manifesto in the ironic manifesto, by disobeying the very decorum of the public sphere, can disrupt the neoliberal and corporate interests that have warped the public sphere’s ostensible democratic function in late liberal society.

‘Futurist Performativity’

The ironic manifesto is not a satiric imitation of the manifesto genre: it is a particular manifesto form. Its irony does not parody the manifesto, but indicates a specific way of functioning that is distinct from the function often attributed to more conventional manifesto forms. Understanding the ironic manifesto’s functional distinction requires close consideration of how the manifesto typically operates. As noted above, the release of UCMeP’s ‘manifesto for privatization’ was just one of many group manifestos issued in the fall of 2009 at the UC. Arguably the most infamous of these was ‘Communiqué from an Absent Future’.10 Authored by the anonymous collective Research and Destroy, ‘Communiqué from an Absent Future’ was released on 24 September 2009, the first day of coordinated action against the budget cuts at the UC system. The document itself was first published to accompany a week-long occupation of UC Santa Cruz’s Graduate Student Commons. It has since been reposted and published numerous times, making it the most widely circulated piece of writing to emerge from the fall 2009 protests at the UC.

The ‘absent future’ referred to in the title targets what the authors argue is the illusion that doling out tens of thousands of dollars in university tuition will necessarily yield a future worth living. Just as ‘we’ long ago recognized that the university’s purpose is not to create ‘a cultured and educated citizenry’, so too must ‘we’ now recognize as a lie any equation of a university education with an investment. With dwindling employment prospects made worse by growing student debt, Research and Destroy argue that the university no longer offers ‘special advantage to the degree-holder’ on the job market. The bankruptcy of the economy has produced a bankruptcy of the university, one that finally reveals what the university has always been: ‘a machine for producing compliant producers and consumers’. For as long as it has existed within capitalism, the authors declare, the university has followed the very logic of capital. The ‘essential function’ of the university is therefore indistinguishable from capitalism’s aim of repro...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgement

- List of Illustrations

- Analogue 0

- Analogue 1

- Duration and Space: The New Manifesto of Occupy Wall Street

- Analogue 2

- Twenty-First-Century Political Art: The Freee Manifesto for Art &Twenty-First-Century Socialism

- Analogue 3

- The Sense of the Manifest/o

- Analogue 4

- Manifesto for Reification

- Analogue 5

- Sustenance: A Play for All Trans [ ] Borders

- Analogue 6

- Provisional Absolutes: The Second Manifesto for Generalized Anthropomorphism

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Back Page