eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

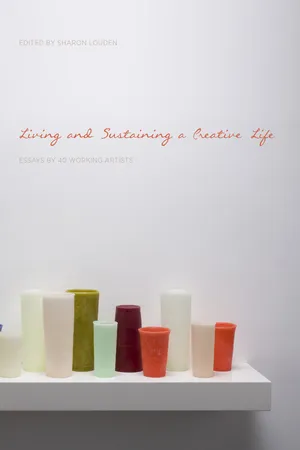

Living and Sustaining a Creative Life

Essays by 40 Working Artists

- 226 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Living and Sustaining a Creative Life by Sharon Louden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CONCLUSION

Ed Winkleman and Bill Carroll

SHARON LOUDEN (SL):I’m here with Ed Winkleman and Bill Carroll in Ed’s gallery in Chelsea on July 17th, 2012, to record a conclusion to this book, Living and Sustaining a Creative Life: essays by 40 working artists. One of the reasons why I asked them to sit and talk with me today is because they both have had many years of experience working with artists and seeing how artists have evolved. Bill Carroll is a “senior” gallerist, if you will, even though he’s not in that role at the moment. In addition to being a fantastic artist in his own right, he serves as the Director of the studio program at the Elizabeth Foundation (EFA); is that correct, Bill?

BILL CARROLL (BC):Yes.

SL:And then we have Ed Winkleman, gallerist, as well as activist through his blog. He has also written an extremely informative book detailing how to build a gallery, entitled, How to Start and Run a Commercial Gallery. One of the reasons I asked both of them to contribute to the book is to hear about their experiences in the art world over the years. I wanted to get their views on whether it really matters if an artist is represented by a gallery, or whether one’s “pedigree” is important to achieving respect as an artist living and sustaining a creative life. Can you talk about that, Ed?

ED WINKLEMAN (EW):I suppose that’s, like, maybe a couple of questions, so maybe we could break it down…

SL:How about if I say this: a lot of artists I have met, especially young artists, feel that when they get out of school they have to have a gallery in order to be considered “worthy” as a professional artist. I’m more interested in asking the question: What defines an artist publicly? Many of the artists contributing to this book talk about the simple sustaining power of just making their work every day in their studio, and that’s enough to call themselves artists. It’s not a public process. And yet they must sustain outside of their studio, as well. Could you talk about that dynamic, perhaps?

EW:I think whether or not you have a gallery is a question a lot of people who identify as an artist are asked almost immediately. And within the population of people who kind of understand how the art world works, it is seen as a milestone. Seen as a potential career goal. But I also find that there are younger artists using the model of building an art career completely independent of a commercial art gallery system, and it is equally viable. I think it doesn’t get as much attention because there aren’t consistent advertising or promotional pushes for those artists. As opposed to a gallery artist who gets more exposure through the promotion of a gallery. So you might get a sense that Artist X, who shows with this gallery in New York, this one in London, and this one in Los Angeles, is having a good career. But truth of the matter is Artist X might not be making anywhere near as much money as Artist Y, who doesn’t have any galleries. But Artist Y isn’t having the ads bought for individual shows, or isn’t necessarily having their work shown at art fairs or these other sort of more public places. So it’s a more under-the-radar sort of career to have if you don’t have a commercial art gallery. I think that confuses a lot of younger artists into thinking that they must have a commercial art gallery to meet their goals. Because how else would they measure it?

Now when I talk a little bit about how to get a gallery in some of my lectures, I start off with the idea that there’s a spectrum of places that you can exhibit your work: everywhere from a restaurant to a museum, non-profit places in between, etc. The commercial galleries have been one choice in that spectrum. What I ask artists who are interested in getting a gallery to really think about is whether getting a gallery helps them meet their goals. Oddly enough, that usually triggers them to say they’re not sure what their goals are. So then I say, okay, that’s really where you have to start. What are your goals? Is it that you want to have, you know, a museum retrospective by the time you’re 50? Is it that you want to be able to live off of your art? I mean, what are very concrete goals you have? And believe it or not a lot of times a commercial gallery can be completely irrelevant to those goals. Figuring out whether or not your goals require you to have a commercial gallery is extremely important and something we talk about.

That said, it’s a little difficult for me, being a commercial gallerist, to really delve deeply into what all of the options outside the commercial gallery system are. I mean, I’m really focused on what we’re doing here. But I know a number of artists have very, very successful careers outside the commercial gallery system. Some of the artists that we work with, for example, we sell some of their work, but nowhere near as much as they show in museums or biennials or other things, and you know, a commercial gallery for them is a nice little extra off the side. It doesn’t even come close to making them the sort of money they get from these other opportunities to exhibit their work.

SL:Bill, what do you think?

BC:I think, when I talk to one of my students at Pratt in professional practice, what we really talk about, first of all, is entering the dialog. The first thing most artists want is to be in their studio making their work, and that’s what they’re dedicated to. And if you just want to do that and then hope it’s discovered after you’re dead, that’s one route. But, with the artists that I’m meeting, first of all, they’ve come to New York to really enter into the dialog. For me, the question is: Do you need to have a commercial gallery to enter into that dialog? And in fact, no, you don’t. There are people, as you were talking about, Ed, those couple of artists that you represent, whose bigger part of their career is actually in museums. I remember one artist in particular, when I was at Elizabeth Harris, that we worked with. At one point we were doing a lot of site-specific installations in our smaller space. This was a big focus of mine with this artist. But very much on a one-shot deal because they were unsalable. At another point, we took on one artist who did these big site-specific installations, which were really not very saleable. But the fact of the matter is she was at that point already a mid-career artist. She had had other galleries at different points, but the main part of her career was in museums, especially university museums. There were a lot of places out there that couldn’t wait to have her come and do a big installation; places that did not care whether they were going to be sold. That wasn’t their primary goal. Because one way or another, no matter how you slice it, galleries are a business, and at some point it becomes about salability.

There are a number of artists who do these site-specific kinds of installations or performances, and can also figure out a saleable part of it. I always think Ann Hamilton’s a great example, who did these amazing things. All the little video things she did were equally good – and were saleable. There are not a lot of people doing the installation stuff who can manage that. That said, I’ve met a number of artists who have their careers either doing the museum thing, where there’s a big audience for that, or are doing other sorts of projects – especially some of these younger artists who are doing all kinds of guerilla-type art situations, where they’re bringing their own friends, that sort of scene.

There are lots of ways to be in the dialog without being in the commercial gallery system. But I think, ultimately, that’s the first decision: is this art-making thing something you’re going to do just for yourself, and you’re not worried about showing at all? I don’t think that is the case with anyone who’s going to read this book. Finally, in terms of making money, I’ve also met a lot of artists who have plugged into art consultants around the country, and who are selling work on a regular basis. Sometimes they are making a lot of money and don’t have a commercial gallery, although they do have some other kind of commercial outlet.

SL:So would it be fair to say that you consider somebody who’s a professional artist just somebody who’s simply creating? Or, is the importance to engage in the dialog paramount?

EW:Well, those are two different things. Somebody who’s simply creating can sort of participate in the dialog, but you obviously can’t engage in the dialog without creating. For instance, we’re just starting to work with an artist who has a 30-page resume of exhibitions and had her very first gallery show at age 60, and did not need a commercial gallery whatsoever to have the success she’s achieved. She’s in MoMA, she’s in the Whitney, she’s in the Biennial, she’s in all the history books. She’s major. She defines a big section of the dialog. She didn’t need a gallery; it was just nice to have after she met a lot of other goals for herself. So, yeah, it’s completely possible outside the gallery. Sometimes it’s probably even easier.

SL:Well, it’s interesting to hear that. I think part of this book is that a lot of these artists do talk about the different road maps that they take to be able to sustain their creativity and living in order to keep going as artists. So, based on what you just mentioned about this artist and her 30 years, can you talk about some of the other artists that you’ve worked with that they have sustained their creativity and livings as artists?

EW:Well, I can elaborate on the one I just mentioned. In addition to teaching, she got virtually every grant known to man. And, again, got it through the strength of her work. To be really honest though, at a certain point the decision to work with a commercial gallery came because she realized that there were no grants that she hadn’t gotten, and it was very unlikely she would continue to get as many as she had because she’d already gotten them all. So that can be one of the factors that can drive somebody into a commercial gallery.

BC:I always say to my students that, in the same way that you’re in your studio coming up with a very individual body of work, that’s really your voice and not like anybody else’s – your career should be the same way. It’s important to compare and contrast paths, of course, but that no two careers look exactly the same. For instance, certainly teaching’s a big part of it. Also, some of the artists at the EFA are graphic designers, and they do it freelance and they get paid a lot of money by the hour.

Two more things artists need to remember: (1) keep your expenses low right from the beginning. I’ve watched a lot of artists, for instance, in the late 1980s, when there was a boom and they really overextended themselves, and then when the crash came they were really not in a good situation. It’s important that even when things are good, you must keep your expenses low… it’s a really good thing. (2) If you’re going to have a day job, try to keep it somehow connected to the art community. I think that for you to spend hours of a day doing something that’s so completely disconnected… even if you’re working part-time like up at the EFA, you’re meeting other artists; there’s a kind of networking that goes on that I think is really important.

I was going to say, I was also thinking of artists who have found other ways to make a living. One artist that I worked with back when I was at Charlie Cowles was an artist who made big sculptures. And in the early 1990s when the crash – that crash, it was two crashes ago now –when that happened – boom. The gallery part of it; we stopped selling completely. He ended up going into public art. So he started applying for all these public art commissions and ended up getting them. Once he had one really big success – he did something in Boston that was a huge success – that really became his career. He now basically does public art. And as far as I know, I don’t even think he has a gallery or has had one for years. But that’s like almost another world he got plugged into, where he’s highly respected; he does these amazing commissions, he knows how to do them, he does them on time, everybody loves them. There are so many different ways you can find as an outlet for your art.

SL:What do you think the expectations are now for an artist, versus, let’s say, 20 years ago? Are they the same after leaving school? Do all newly-minted art school grads expect to get a gallery immediately? Is being part of a community important? That sort of thing?

EW:I think you have to go back more than 20 years. When I go back 20 years, I think it’s very similar. It was sort of after the Neo-Expressionists and everybody was just making tons and tons of money. I think the expectation, to get really historical about it, started at more or less the same time that Warhol started to take off. You could be both a rock star and an artist at the same time, and whether or not it was really realistic, that started to become the dream anyway. I think once that became the dream, that trickled down into art schools. Everybody coming out assumed… I mean, not everybody – I guess there was still a generation of students being taught, “these galleries are your enemy; you will never make any money.” Some of them bought into it, but the smarter ones were looking at the other people making money and thinking, “well, you’re saying that but look at them over there.” So 20 years ago I think we were well into the era when artists assumed that they could have a successful career living off their art. And I would say at least that segment of the artist population dominated who was approaching the galleries. At that point, artists approaching the galleries were assuming that they were going to be able to live off of selling their art. So it really hasn’t changed that much.

SL:Do you think, though, that there’s an expectation now versus before? The expectation being that it will automatically happen?

EW:Well, I think there are more galleries than ever before; the market’s a lot larger, that’s for sure. So yeah, the expectation is in place because of that. But, honestly, I go back to the artists that lost their galleries in the early 1990s, and those are folks who were out of school 20 years ago now. All of the East Village crowd – they all assumed they were going to be the next big rock star. This is why they moved to New York; this is why they were going to the East Village. What Bill said is really important, though: a lot of them thought the money was never going to end. And the market did crash, and they were completely unprepared. I think in terms of preparing artists to have a lengthy career and make money, somebody has to show them that this will always go up and down. There will never be a constant rise in the market. I mean, really great artists, who should have known better, got wiped out at this last downturn.

SL:In 2008.

EW:Which is ridiculous. I mean, they were so unprepared for it to come back down again. It’s just shocking to me that they didn’t see that that was a very strong possibility. So I think that’s a big deal to emphasize.

SL:Bill?

BC:Well, as you said, to go back historically, which is a really long way, but when I was in art school the model was [Willem] de Kooning, who had his first one-person show at 40. You didn’t think about showing the first ten years out of school. And it took a long time to actually have work that was mature enough that you would dare put it out there in that dialog. And obviously that changed, and I do think the big change was the boom in the late 1980s, which to me was pretty much the exact same as this last boom. There was this boom, and everybody took it for granted. Everybody was making tons of money, every show we had was selling out, and people took it for granted. And then, boom, it’s over. And yes, it’s really important for artists to realize that. And that’s something I really emphasize when I’m talking to young artists: you need to be able to get through the tough times. Just because you’re selling a bunch of stuff right now…. It’s a very fragile world! It’s the first thing people cut out when there’s a recession [buying art]. You need to be ready when that happens. I have a number of artists at the Elizabeth Foundation; I can think of one artist in particular, who had a gallery and part of her income besides teaching was at least $50,000 a year from her art. And it just stopped completely. Suddenly she doesn’t have $50,000 that she had before, because when this crash happened, people stopped selling. It was a done deal.

So you have to be in it for the long haul. I do think that during the moments of boom, whichever one you talk about, the young artists expected immediate gallery representation when they graduated. I talked to someone up in Columbia University recently who told me that it was a real problem; that it had gotten to the point where everybody who left Columbia immediately walked into some big gallery career. One of the problems with that is that the few who didn’t get immediate representation thought that they were failures, a year out of graduate school. They thought that their career was already over. I thought those were really unrealistic expectations.

I think in that way the downturns are a good thing. This last one was like a light switched off from o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface Sharon Louden

- Introduction Carter E. Foster

- Essays Adrienne Outlaw

- Amanda Church

- Amy Pleasant

- Annette Lawrence

- Austin Thomas

- Beth Lipman

- Blane De St. Croix

- Brian Novatny

- Brian Tolle

- Carson Fox

- David Humphrey

- Ellen Harvey

- Erik Hanson

- George Stoll

- Jay Davis

- Jennifer Dalton

- Jenny Marketou

- Julie Blackmon

- Julie Heffernan

- Julie Langsam

- Justin Quinn

- Karin Davie

- Kate Shepherd

- Laurie Hogin

- Maggie Michael and Dan Steinhilber

- Maureen Connor

- Melissa Potter

- Michael Waugh

- Michelle Grabner

- Peter Drake

- Peter Newman

- Richard Klein

- Sean Mellyn

- Sharon L. Butler

- The Art Guys

- Thomas Kilpper

- Timothy Nolan

- Tony Ingrisano

- Will Cotton

- Conclusion Ed Winkleman and Bill Carroll

- Acknowledgments