![]()

Chapter One

Sets, Screens and Social Spaces: Exhibiting Television

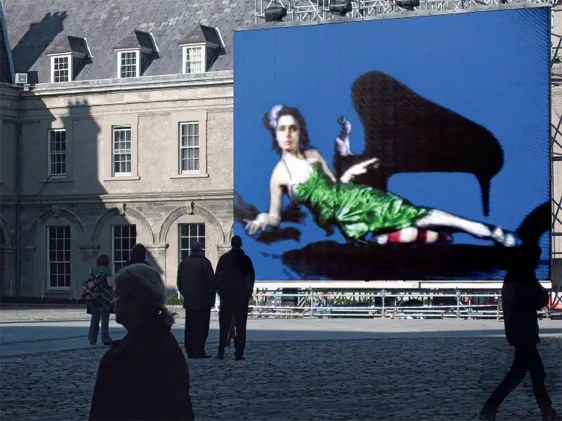

Above: James Coleman, So Different …

and Yet, 1978–80. Video installation.

Performed by Olwen Fouéré and Roger

Doyle. © James Coleman.

If the word ‘television’ in ordinary usage applies not just to the medium as a whole but, more precisely, to its materialization as the receiving set, this emphasizes just how determining the aspect of ‘setting’ and ‘placing’ is for a medium that deprives distance as well as proximity of their traditional stability and hence of their power to orient. What is distant is set right before us, close up; and yet what is thus brought close remains strangely removed, indeterminably distant. And what is traditionally proximate is set apart, set at a distance.

Samuel Weber, Mass Mediauras: Form, Technics, Media1

[Nam June] Paik’s work joins the most ephemeral and the most ‘tangible’ aspects of television: on the one hand the realtime flow of signals and, on the other hand, the TV-set as a piece of furniture in the private home, the place where machine-time and life-time are integrated. Such concerns seemed to fade from view as video art asserted itself as a specifically artistic medium […] when these concerns re-emerged in the art of the 1990s, they re-emerged not within the framework of video art, but […] in terms of a new artistic interest in inhabited places and social spaces.

Ina Blom, On the Style Site: Art, Sociality and Media Culture2

Introduction: Exhibiting Television

In a widely-cited analysis, which engages with television as material object, medium and cultural technology, Samuel Weber identifies a complex dynamic of distance and proximity, noting that what is brought close through TV nonetheless remains removed and distant, while what is traditionally close acquires a quality of removal. Significantly, Weber is not solely concerned with practices of television production and reception; he also refers to the ways in which television is materialised, conceptualised and described in language. Even though he refers to ‘ordinary’ usage of the term television, his analysis highlights its slipperiness, tacitly acknowledging the ways in which television actually evades representation, despite (or perhaps because of) its apparent familiarity. Even though Weber does not specifically address the relationship between television and contemporary art, his text is important in illuminating the specific challenges involved in theorising the exhibition of television both within and beyond the museum. In part, this is because Weber’s analysis has elicited a valuable critique in the form of Anna McCarthy’s argument for a more site-oriented approach to television’s material culture and place.

McCarthy situates Weber’s analysis in relation to a broader preoccupation with television as a form of ‘remote inscription that produces—and annihilates—places: the place of the body, the place of the screen, the place of dwelling’.3 She acknowledges that ‘like all technologies of “space-binding,” television poses challenges to fixed conceptions of materiality and immateriality, farness and nearness, vision and touch’. This is because, as she points out, television ‘is both a thing and a conduit for electronic signals, both a piece of furniture in a room and a window to an imaged elsewhere, both a commodity and a way of looking at commodities’.4 Television is framed by McCarthy as analogous to the network. She notes that because of its ‘scalar complexity’ it can be considered at different scales, which include a close-up on the network’s ‘terminal point’ of the television set, on specific viewing subjects or groups, or attention to what she terms ‘centralizing transmissions’.5 Focusing on one particular level, however, involves neglecting the others and the tensions between them, and it is precisely because of this complexity that, McCarthy argues, television has proved important in philosophical discourse, as an embodiment of the tension between the ‘global’ and the ‘local’. At the same time, however, television’s status as a material object is often overlooked, with the result that the television apparatus (as distinct from television’s historical association with Fordist processes of standardisation)6 is routinely conceptualised as an agent and emblem of placelessness, without sufficient attention to the ways in which television is encountered within the multiple spaces of everyday life, such as airports, restaurants, supermarkets and shopping malls.7 Consequently, McCarthy argues for an examination of television’s role in organising ‘particular relations of public and private, subjects and others’ that characterise everyday places.8 Informed by McCarthy’s approach, this chapter focuses on art galleries, museums and other spaces of exhibition, as specific contexts and places in which television is encountered, and in which its complex materiality, and simultaneous status as thing, conduit for signals, furniture, window, commodity and way of looking at commodities, can become especially pronounced. I also consider how television’s mutability, with respect to materiality, cultural status and modes of sociality, has been registered and articulated within art installations and exhibitions, through practices of curation, installation, display and design.9

There are many difficulties involved in analysing the particular relations produced by the exhibition of television, not least those involved in actually defining ‘television’ as an exhibited object. According to Weber, the term television is commonly used to signify both the medium and its materialisation in the form of the ‘receiving set’, and its receptive function is integral to his account of the proximate and distant. Receiving sets have certainly been important in the exhibition of television, perhaps most notably in the case of Nam June Paik’s Exposition of Music—Electronic Television at Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, which featured numerous modified TV receivers, tuned to what was then Germany’s only television station.10 The opening hours of the gallery, located in a villa that was also the private home of gallerist Rolf Jährling, had to be altered for the duration of Paik’s exhibition, because TV services were then only available in the evening. According to Weber’s definition, there are certainly a great many instances in which video monitors are enabled to receive electronic signals—most obviously in works involving closed circuit television. But, despite the importance of Paik’s show, it is relatively unusual to encounter functioning television receivers in gallery or museum spaces. In fact ‘television’ is more likely to be signified by the staging (through arrangements of lighting, furniture and hardware) of viewing environments, often with domestic associations. Significantly, the quasi-domestic setting of Galerie Parnass enabled the modified television sets to be encountered simultaneously as furniture, things and conduits.

The museum and gallery spaces in which television is exhibited also need to be differentiated from the ‘everyday places’ highlighted in McCarthy’s account. In fact, for some theorists, museums are important precisely because of their difference from sites of material display considered more mundane. Andreas Huyssen, for example, values the museum as a space in which to encounter ‘objects that have lasted through the ages’, differentiating these objects from ‘commodities destined for the garbage heap’.11 In Huyssen’s model, the function of the museum is to counter, rather than simply compensate for, the dissolution of material experience attributed to television; to ‘expand the ever shrinking space of the (real) present in a culture of amnesia, planned obsolescence and ever more synchronic and timeless information flows’.12 Huyssen does not consider how exhibitions of artworks engaging with the materiality of television might offer a means of engaging critically with the economic logic of planned obsolescence, or indeed the role played by the museum in this economy.

This brings me to the next challenge involved in theorising the exhibition of television—the fact that its material form is subject to change over time. Here I am referring not just to the displacement of the console as ‘receiving set’ by newer devices, but also to the fact that displays of television monitors have sometimes featured within, for example, the design of television studios, particularly newsrooms. There are also many other situations, sometimes framed as ‘special events’, where the technology of broadcasting is placed on display, such as (for example) satellite broadcasting events, in which control rooms, technicians or other elements of the technological apparatus of television are made visible to audiences.13 These changes are registered, albeit somewhat obliquely, in Weber’s account of television. Informed by Walter Benjamin’s analysis of the baroque theatre as an allegorical ‘court’, in which things are brought together only to be dispersed, Weber proposes a parallel between the disordered scenery of baroque allegory and the forms of disorder that characterise television, emphasising that even though television ‘tends to unsettle’, through its operations of displacement and setting apart, it also ‘presents itself as the antidote to the disorder to which it contributes’.14 To illustrate this point, Weber alludes to the ‘infinitely repeated sets of television monitors’ favoured in the studio backdrops of global television news networks such as CNN, which, he argues, imply that an integrated whole might somehow emerge out of indefinite repetition.15 It is possible, however, that television’s self-exhibition as ‘antidote to disorder’ might actually be a stylistic response to the institutional disorder of US broadcasting. Here I am referring to John Caldwell’s analysis of stylistic excess in US television during the 1980s, which was partly shaped by the proliferation of new networks, including CNN.16

Above: The installation of The Amarillo

News Tapes, 1980) by Doug Hall, Jody

Proctor and Chip Lord, Broadcast Yourself,

Hatton Gallery, 2008. Photograph by

Kevin Gibson, Hatton Gallery, Newcastle

for AV Festival 08.

Above: The living room installation

featuring single channel video ‘TV spots’

by artists including Ian Breakwell, Chris

Burden and Wendy Kirkup and Pat Naldi

(at the opening), Broadcast Yourself,

Hatton Gallery, 2008. Photograph by Kevin

Gibson, Hatton Gallery, Newcastle for AV

Festival 08.

In this chapter, I focus on specific encounters with television as a material object within artworks and exhibitions. But rather than treating galleries and museums as ‘everyday’ contexts, I consider how the exhibition of television actually articulates a shifting, and sometimes fraught, relationship between the museum and the realm of the everyday. I argue that practices of exhibiting ‘television’ communicate changes in the form and function of museums, which have historically functioned as social spaces organised around material display. As Tony Bennett has demonstrated, museums developed historically and continue to operate in many instances: as important settings for the ordering of social relations, through processes of classification and categorisation and the integration of objects into narratives of progress and development.17 These mechanisms are certainly very different from television’s own production of order through disorder, as theorised by Weber. Nonetheless, my research suggests that artists and curators have sometimes used their engagement with television to assert the traditional role of the museum or gallery, as institutions of civic education and reform. Through its operations of critique and classification, the museum offers a potential antidote to the framing of television within art discourse as a technology of consumption implicated in the production of cultural or social disorder. Most of the examples that I discuss, however, do not conform to this model. Instead the exhibitions and artworks highlighted in this chapter tend to articulate a reflexive engagement with the historical context of the museum.

Rather than offering a comprehensive survey I identify some significant moments in the exhibition of television, as material object and medium, since the 1960s, focusing particularly on projects that demonstrate the continued significance of Nam June Paik’s thinking in relation to sociality, as theorised by Ina Blom. I am also interested in artworks and exhibitions that engage with television as a mutable cultural form, through the reconfiguration of installations over time or through the development of retrospective modes of exhibition-making. Much of this chapter is concerned with theorising this retrospective turn, which emerged toward the end of the 1990s, but which has become particularly pronounced since the early 2000s.18 My discussion focuses on four exhibitions; Broadcast Yourself, curated by Sarah Cook and Kathy Rae Huffman at the Hatton Gallery, Newcastle and Cornerhouse, Manchester (2008), Changing Channels: Art and Television 1963–1987, curated by Matthias Michalka at Museum Moderner Kunst (MUMOK) Vienna (2010), Are You Ready for TV?, curated by Chus Martinez at Museum d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA), Barcelona (2010–2011), and Remote Control,19 curated by Matt Williams at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), London (2012).

These are just a small selection of the many TV-themed exhibitions ...