![]()

Chapter 1

Doubly Immortal: The Song of Songs (1933)

A direct product of male desire and fetishistic transferral, art in this film simultaneously intensifies and displaces life; it causes both ecstasy and trauma. Though Mamoulian’s camera frequently lingers on Dietrich’s face itself in order to open intimate windows on her ever shifting appearances, it spends almost equal time to offer us images of her statue in scenarios of what Gaylyn Studlar would call ‘iconic textuality,’ that is, highly choreographed scenarios emphasizing the sign as a creation independent of its referent.1

(Koepnick 2007: 47–48)

In 2011, the Deutsche Kinemathek received a gift for its Marlene Dietrich Collection: a sculpture – a life-sized bronze nude – The Song of Songs, a replica of the figure by Salvatore Scarpitta that had played a starring role, as Lutz Koepnick notes, in the 1933 Paramount film of the same title. Announcing the gift in its newsletter, the Kinemathek explained the origins of this bronze cast, made, ‘as a replica of the original,’ in the 1990s (2011). But the term ‘original’ is something of a misnomer, or mystery here. As the short article about Stella Cartaino’s (the artist’s granddaughter) gift also notes, at least three identical sculptures were made for the film. The sculptures were all cast in plaster from the same mold, so there really was no original. But certainly the two surviving plasters (one was destroyed on film) are more original than the more durable bronze that was donated to the museum.

That object – the bronze figure of Marlene Dietrich, which came into being around the time of her death, more than 40 years after Scarpitta’s, and some 60 years after he had modeled the sculpture; and which went on exhibit in the Kinemathek’s ground floor showroom in 2011 – is a paradoxical artifact. Scarpitta generally destroyed his molds, so his son, Salvatore Jr. (also an artist), would have made the mold for the bronze cast from the plaster that his father had retained, which itself would have been cast in a mold, made from the impermanent clay original Scarpitta created ‘of’ Dietrich. The bronze is thus four processes removed from the hand of the artist and, you might say, five generations removed from the movie goddess whom it portrays. It is a reproduction of a sculpture made for the movies – one conceived as a movie star. The statue, director Rouben Mamoulian wrote when trying to cast the role, ‘should be a masterpiece because it is not merely a prop in the picture but a central point around which the whole story revolves […] it will have as many closeups as any star.’2 Note here the double meaning of the word ‘cast.’ The Kinemathek’s bronze is not exactly a work of art and not quite a prop. If it has an aura at all, it is a reconditioned aura; it is, in a sense, a reification of ephemera: the residue of the very particular type of aura that attaches to legendary stars such as Marlene Dietrich.

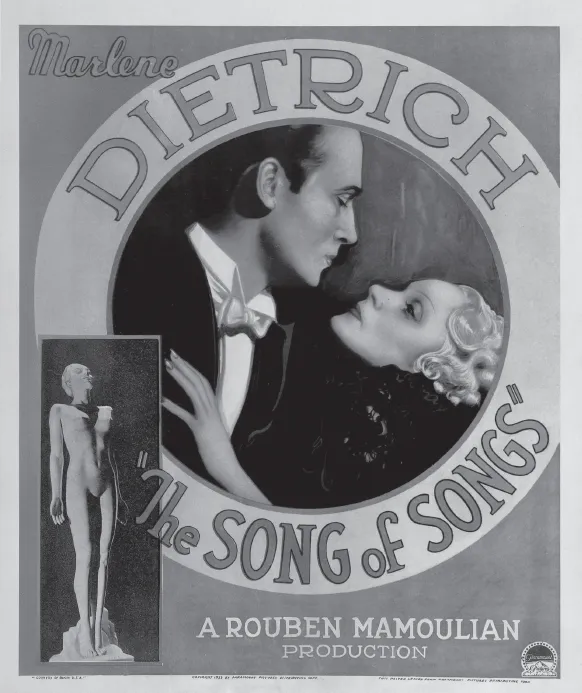

Figure 4: Poster for The Song of Songs (Mamoulian, 1933).

The Song of Songs was Paramount Pictures’ 1933 adaptation of Prussian writer Hermann Sudermann’s 1908 novel Das hohe Lied, a story that had seen two previous Hollywood adaptations: The Song of Songs, 1918, directed by Joseph Kaufman and starring Elsie Ferguson; and Lily of the Dust, 1924, directed by Dimitri Buchowetzki and starring Pola Negri, both for Famous Players–Lasky. The 1933 Paramount version was produced and directed by Rouben Mamoulian, who was a co-author with Leo Birinsky (as Leo Birinski) and Samuel Hoffenstein of the screen adaptation of Sudermann’s novel and the American playwright Edward Sheldon’s play based upon it. The film, then, not unlike the bronze sculpture that descended from it – and like all film adaptations, really – is generations removed from an original source (the Sudermann novel): a remake of a film adaptation of a play based on the novel. The question of authenticity or originality is moot; the aura is already withered.

In The Song of Songs, which is set early in the last century, Marlene Dietrich plays Lily Czepanek, an innocent but sensual, orphaned country girl who moves to Berlin. Working in the bookstore owned by her Aunt Rasmussen (Alison Skipworth), she meets Richard Waldow (Brian Aherne), a handsome young sculptor who lives and works across the street. She succumbs to his entreaties to pose for him and becomes the inspiration and model for his life-size nude, ‘The Song of Songs,’ and then his lover, marking the beginning of a precipitous fall from innocence. Taken with her, Richard’s wealthy, decadent client, a retired Colonel, the Baron von Merzbach (Lionel Atwill), persuades the ambivalent and weak-willed artist to abandon Lily to him and purchases the cooperation of her aunt. Bereft, she is compelled into a loveless marriage to the Baron and turned into a beautiful but unhappy sophisticate (taken home to a neo-medieval, almost expressionist castle and instructed in piano, song, dance, French, and – it is implied – depraved sexual acts). A recriminatory act of infidelity (or the appearance of one, meant to hurt a visiting Waldow more than her husband) leads to her banishment and downfall, a (rather glamorous) downfall from which her reunion with Waldow at the end of the film redeems her. The loss of innocence theme was preserved from Sudermann’s novel in Sheldon’s play and both previous adaptations. The correspondence between art and sensual passion that comes to exemplify Lily’s spirit and self-image also derives from Sudermann. Much of the narrative, however, was changed substantially in the Paramount adaptation and the sculptor character and modeling theme were wholly an invention of Mamoulian’s film.3 Sculpture, it can be inferred, was imported into the story to play a particular role (or roles).

Hermann Sudermann (1857–1928), the ‘Balzac of the East,’ although little remembered now, was a towering figure in drama and literature in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. An editor of the radical newspaper Deutsches Reichsblatt from 1881 to 1889, and already the author of collected stories and a novel, Frau Sorge (1887), Sudermann gained enormous acclaim with his first play, Die Ehre (1889), which purportedly stirred Berlin youth to riot or protest over three days. Eleanora Duse, Sarah Bernhardt, and Helena Modjeska starred in famed productions of Sudermann’s Heimat (Magda in English).4 Sudermann’s plays were performed in the premier theaters of Berlin, Vienna, Paris, Rome, New York, and as far as Japan.

Among the forty-plus other filmed adaptations of Sudermann’s works are F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), based on Sudermann’s short story ‘Die Reise nach Tilsit’/‘Trip to Tilset,’ and Flesh and the Devil (Brown, 1927), with Greta Garbo, based on his play The Undying Past.

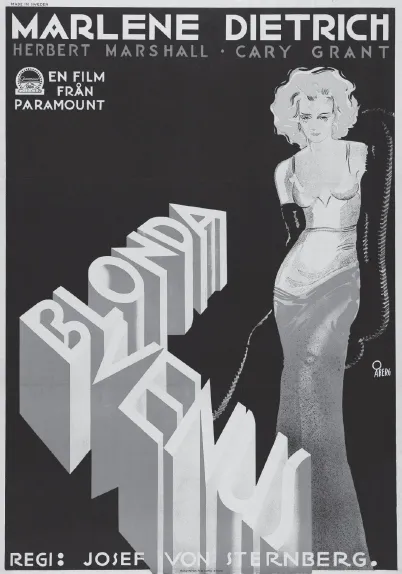

Marlene Dietrich starred in The Song of Songs, her first Hollywood film not – for personal and contractual reasons – directed by Josef von Sternberg. She was not pleased about this; it evidently took a suit to bring her to work but, according to several sources, finally the production offered her a critical opportunity to wrest some control over her own image and craft (Anon 1933: 18).5 There is a fascinating metacinematic paradox here, then. Dietrich – famously a creation of von Sternberg’s (‘Like an artist working in clay, von Sternberg has molded and modeled her to his own design, and Marlene, plastic and willing to be material in the director’s hands, has responded to his creative moods’ [Tolischus 1931: 28–29; 129]) – took on a role in the film in which she was literally modeled in clay by a sculptor, and in which the Pygmalion theme was telescoped (‘you modeled her in marble but I modeled her in the flesh, so to speak; I’m a bit of an artist myself …,’ says Merzbach, Song’s ersatz Svengali), yet in undertaking the part without her Pygmalion (Svengali?), learned to master modeling herself in light.6 Given that the sculpture theme had entered the Song of Songs script – after several revisions – sometime after Dietrich’s services were secured, it is entirely possible that she inspired it. Although her prior film, von Sternberg’s Blonde Venus (1932), had little to do with high art, posters and other elements of the advertising campaign featured variations on a sketch of Dietrich as the Venus de Milo, with the sculpted goddess’s naked torso approximated by a skimpy, transparent, close-fitting bodice and her broken arms suggested by long black gloves [Fig. 5].

The motif effectively invokes art, beauty, eroticism, and Dietrich’s status as a movie goddess, in one figure: one – as Mary Beth Haralovich points out – that is iconographically unrelated to the character, Helen Faraday, that Dietrich played in Blonde Venus. Perhaps this overdetermined image showed Mamoulian how he might give visual form to some of Sudermann’s more problematic themes. It is perhaps no coincidence that in an epistle prepared in defense of the nudity of the statuary in The Song of Songs, Mamoulian asserted that the ‘first synonym for beauty that comes to anybody’s mind is always Venus de Milo’ (Mamoulian 1933).7 But contradictions around the significance and signification of nudity resound in The Song of Songs, as is vividly captured by discrepancies between the language of the letter contracting the titular sculpture and subsequent accounts.

Figure 5: Poster for Blonde Venus (Von Sternberg, 1932).

The contradictions revealed in two documents – a letter contracting sculptor Salvatore Cartaino Scarpitta (1887–1948) to create the titular sculpture for Paramount’s film and a notice in a Chicago paper noting the proximate and competing attractions of Dietrich and Sally Rand in local theaters – are only some of those which attend the complex roles that real works of art play in this fiction film and others. The ‘masterpiece in marble’ that the newspaper item in nearly the same breath reveals to be an end run around the censors was indeed the work of an accomplished artist of some repute, but it is not made of marble. Indeed, The Song of Songs illustrates the process and the progress of the sculpture from its inception in a sketch, then a small maquette, to a full-scale armature upon which plaster is built up and then clay modeled. Numerous scenes show the sculptor working the pliable clay – in fact, much of the subtext depends upon such images. Generally, such an additive sculptural process results in a form from which a mold is made, in turn from which a sculpture is cast, typically either in bronze or plaster. Marble, on the other hand, must be carved; it is worked subtractively.

The anonymous Chicago reviewer was understandably confused about the medium, however. The movie itself wants to have its marble and mold it, too; it bares some of the devices of sculpture but not those of the movies: featuring a veritably documentary scene about process yet seeming to count on its audience’s ignorance of or indifference to sculptural materials and techniques. Not only does publicity for the film tout the ‘poem in marble conceived by the noted Italian sculptor S.C. Scarpitta,’10 but the very script insists, too, upon the statue’s marmoreal standing. ‘Next the clay,’ says Waldow, the fictional sculptor, as he completes his sketch, continuing – as if one could cast in stone – ‘then the marble: The Song of Songs in marble!’ Later, the libertine Baron von Merzbach echoes this material claim, saying to Richard of Lily, the model and inspiration for the figu...