![]()

Part I

Another Kind of Introduction

![]()

Why Office Killer Deserves Your Attention (And How It First Grabbed Mine)

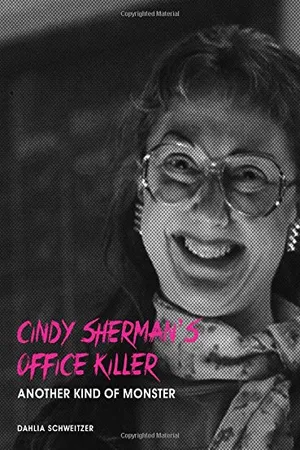

For some of us, spiritual introspection leads to a sense of calm, center and comfort. For others, though, a critical review of the images and texts around them is an essential part of understanding themselves and the world. I’m one of those others. At first glance, the divergent and occasionally intersecting paths I’ve followed—curating an exhibition on postmodernism for Wesleyan University; publishing books of short stories; writing and producing a music album; touring Europe for three years as a musician and performance artist; displaying my photographs in both solo and group shows; completing an MA in criticism and theory at the Art Center College of Design; and writing a book on Cindy Sherman’s film Office Killer—might appear to have neither a common theme, nor purpose. In fact, I see them all as part of a larger whole; elements that have contributed to my desire to combine film with academic theory and research in order to explore individual moments in a larger cultural narrative.

Relationships between self and Other, and the tensions between boundaries of gender, identity, and public versus private space, fascinate me. I find those places where things are undefined, evolving, or under conflict to be the most interesting because I see myself and the world as all of those things. In the twenty-first century, the borders between public and private space are growing more blurred and unstable. I am fascinated with the erosion and evolution of these borders, as well as with the ease with which we could morph and adapt our identities. Despite being a writer, I am drawn to visual representations of these ideas. And it is through cinema as a fixed representation of cultural phenomena and processes that I continue to be most fascinated in studying the shifting manifestations of boundaries of gender, identity, and the internal and external. A close look at one film merely opens up the door to a larger conversation: films, after all, are sociocultural constructs, the text upon which are inscribed notions of otherness, gender, sexuality, and differences—as well as a variety of historical, social and cultural discourses. By studying film, it is possible to study the world, and by studying specific films, it is possible to appreciate and deconstruct specific aspects of society.

This is why I decided to return to a formative film from my past—Cindy Sherman’s Office Killer (1997)—for a closer look. The movie—representing Sherman’s only foray into film-making—is set in a 1990s America in which the traditional boundaries between interiority and exteriority, and by extension the public and private, have been all but eradicated. Sherman presents a material body that, even if it must be maintained with Windex and Scotch tape to remain so, locates the irreducibility of the two realms. My analysis of this film expands my own internal dialog regarding the production of self by way of the staging of the body. It also complicates my questions about the public and private with its representation of torn and open bodies; bodies that are literally toying with the boundaries of inside and outside. Our fascination with technological reproduction and machines, our evolving definitions of self, Other and intimacy, play out in what at first glance might seem like a simple little horror film. With every viewing, however, I realized that there was nothing simple or “little” about Office Killer. In fact, Office Killer, in a charmingly effortless way, encapsulates all of my interests—theoretical, visual, and cultural.

My goal is to valorize Office Killer, which, despite being critically and commercially ignored, is a very important film, one rich with material for students of film theory, criticism, and production. Ideally, intellectuals should be able to go back and forth between academic theory and mass media, since the two are inexorably linked. Mass media should not be discussed in isolation, because it is not intended to be viewed as such. Mass media references and regurgitates elements of high culture and low culture with the same easy fluidity; a cyclical vortex of cultural ideas and concepts. Mass media is media for the masses. As Camille Paglia wrote, it is our culture.1 It is integrally connected to the society to which it appeals. This is part of the explanation for its authenticity. While the box office failure of Office Killer prevented it from becoming any sort of mass media sensation, it is still, as a commercial film, a product of mass media, and it is therefore integrally connected to the society that existed when it was released. It is a cultural archive for a particular moment in time, just as much as it is a reference point in the chronology of Cindy Sherman’s work.

One of the most interesting questions Office Killer raises is: Why are we not talking about it? The second question is: Why should we? I begin this book by addressing these questions, as well as explaining my personal connection to Cindy Sherman and to Office Killer, along with outlining the reasons it remains so intensely problematic, and providing an overview of the film.

In the second chapter, I provide a general summary of Cindy Sherman’s life and career in order to contextualize Office Killer within it. Since Office Killer is usually left out of any conversation about Sherman’s work, it becomes all the more important to acknowledge its place—intellectually, artistically, and chronologically. I also look at the production of Office Killer, and its problems of marketability.

In the third chapter, I provide a shot-by-shot analysis of all the film’s significant scenes. This kind of analysis not only permits a close reading of Sherman’s visual style and how it carries over onto the big screen, but it also helps pick apart the many layers of nuance and reference. Office Killer is an incredibly complex film, and even after countless viewings, I discover more and more within it.

In the fourth chapter, I contextualize the film within its Zeitgeist. While many films could happen anywhere, at any time, Office Killer could not. Office Killer would make no sense outside of its place and time. Not only are its characters products of the late 1990s in a way that would not carry over to another decade, but the conflicts and tensions within the film itself are particular to that era as well. Therefore, it becomes essential to any conversation about Office Killer to examine the larger issues of the time: AIDS, technology, and the evolving workplace. I also look at Office Killer within a larger film narrative, drawing close connections between three films—Working Girl (Nichols, 1988), Basic Instinct (Verhoeven, 1992) and What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (Aldrich, 1962)—with which Office Killer has many parallels. In the same section, I describe the characters most important to the film’s story: Dorine, Norah, Virginia, Kim, and Dorine’s mother.

In the fifth and final chapter, I explain how Office Killer was right about everything—even while managing to fail so miserably. Connecting Office Killer to a conversation about Sherman’s work and placing it in a larger context, I draw parallels between Dorine and Sherman, between Office Killer and the 1990s, and between Office Killer and the twenty-first century. By studying this film, we can both learn about the era from which it came, and also who and what came after.

*****

In the fall of 1997, I wrote to Cindy Sherman. I did not know what to do with my life, and I figured I might as well ask the person most relevant to my career what I should do next. “Dear Ms. Sherman: Tell me what to do with my life,” I wrote. Not quite as precociously, but that was the sentiment. She wrote back, and thus began a brief correspondence, over the course of which she told me that she was working on a movie.

Of course, I wanted to see that movie more than anything, partly because I take my idols seriously, and also because it sounded amazing. Cindy Sherman does a horror film! But few others were as excited, including Miramax, who bought the film. Office Killer fizzled, so I had a hard time finding it. I did not see it until I moved to New York a year later, and the act of seeing it was so consuming I cannot even remember the venue. I think it was at the Museum of Modern Art, which is the same place that showed her complete sixty-nine “Untitled Film Stills” in 1997.

The first time I saw the movie, I remember being disappointed. Not because it was a bad movie, but because, at first, it seemed so different from Sherman’s photographs. For one, Sherman was not in the film. Since most of Sherman’s fame and notoriety have come from how she repurposes herself in her work, her absence from the film felt conspicuous. This may have been why so many other critics chose to ignore it. Another diversion from everything else she was known for was that the film was titled. This was one more sign that things were not going as expected. Suddenly, her work was labeled, leaving behind the realm of innuendo and suggestion. The queen of the implied narrative had finally told an actual story.

To make matters worse, it was a story that seemed clear, simple and comfortable in its clichés. It was a horror film. There were dead bodies. There was a killer, a self-styled detective, and murder. There was Molly Ringwald. It seemed so frustratingly easy to decode that many did not even bother. They just ignored it, even claiming that Sherman also wanted nothing to do with the movie either: “Sherman does not consider Office Killer to be part of her own body of art, since she was more of a hired gun to direct the picture,” wrote Catherine Morris in The Essential Cindy Sherman.2

But Sherman was not simply a hired gun. In the June 1997 issue of Art in America, Sherman herself acknowledges that the general idea for the story was hers, that she was involved in preproduction, that she gave specific instructions to the cinematographer and the actors about what she wanted, and that she played a direct role in the editing. Even producer Christine Vachon says that Sherman had full creative control. But the movie bombed, and everyone, including Sherman, stopped talking about it.

Part of the problem is that the movie is not really a horror film, or even a send-up of a horror film. It is somewhere between genres; more of a dark “chick flick” combined with elements of film noir, black comedy and horror. All the main characters are female, and their relationships echo a Joan Crawford-led women’s picture from an earlier era, where films like The Women (Cukor, 1939) and Mildred Pierce (Curtiz, 1945) explored the complicated interpersonal dynamics between women and their struggles for men, power, and independence. There are also numerous thematic and atmospheric parallels between Office Killer and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), another mix of horror and melodrama from three decades earlier. On one hand, the intensity of some of Office Killer’s scenes, and the conflict and competition between the film’s various women, support the film’s placement in the category of melodrama, while other elements are more reminiscent of film noir and horror. To complicate categorization further, the movie also has a defiant sense of humor.

When analyzing Office Killer, there is no question that it is fun to watch the movie with an eye for Sherman’s style, to match up shots from the movie with her photographs; but it is still a movie, and therefore much of its meaning, significance, and style of execution are fundamentally different than a photograph’s. It is both relevant and provocative that this is Sherman’s only work with sound, motion, and a title, and which involves other people besides herself. So why there is so little discussion of Office Killer as a film? The film is almost completely ignored in discussions of Sherman’s work post-1997, and when it appears, it is merely as a means to turn the conversation to her photos. This is not completely unusual: critics tend to flatten the differences in Sherman’s work, fusing her various photographs together as continuations of the “Untitled Film Stills,” interpreting every work in relation to what came before. This is partly because of the narrative quality that builds easily when her individual photographs are organized in a row, since alone each seems fragmentary, speaking merely in notation; but it also creates a dangerously limited, one-dimensional perspective that prohibits any real complex understanding of her work. If we examine the film, and the way that, like her photos, it twists and parodies horror, fashion, and melodrama, we can not only understand why the film is fundamentally upsetting, but we can also acknowledge why it remains so relevant, and why it remains such an important component in her body of work.

While the film can be seen as a summation of Sherman’s photographic themes, it also deserves its own conversation. Not only does addressing the movie provide us with valuable insight into the American psyche at the end of the twentieth century, but it also alters our conversation about Sherman’s photos. Most dialogs about Sherman’s photos start and stop with a discussion about the feminine image, but Office Killer takes the conversation to another level entirely. If we start to think about Sherman as an artist transfixed by the materiality of the body; if we look at her photos as reflections of the themes so clearly evident in the movie (rather than only looking at the movie as the neglected kid sister to her photos); if we start to pick up on the aggression inherent in her depictions of women, the lack of pin-up glamour, the steely solitude, and the decaying bodies: how does that reinvent the “Untitled Film Stills,” the “Centerfolds,” or the “Fashion” series? How does that change our understanding of the entirety of Sherman’s work? If we take the time to examine her film with the attention it deserves, if we zoom out to evaluate its cultural and social context, we gain a richer understanding not only of Sherman’s messages, but also of a specific era in American history.

![]()

Character Reference Guide

Dorine Douglas (Carol Kane): Our protagonist, Constant Consumer magazine’s best copyeditor.

Daniel (Michael Imperioli): Norah’s boyfriend and office technology guy.

Carlotta Douglas (Alice Drummond): Dorine’s mother.

Peter Douglas (Eric Bogosian): Dorine’s father.

Mail Boy (Jason Brill): Distributes the mail and flirts with Kim.

Kim (Molly Ringwald): Office sexpot, fashionista, and gossip; having an affair with Gary Michaels while flirting with the Mail Boy and Daniel.

Mr. Landau (Mike Hodge): Head of Constant Consumer magazine’s copy department.

Gary Michaels (David Thornton): Writer at Constant Consumer magazine and office lech.

Mrs. Michaels (Marla Sucharetza): Gary’s wife.

Norah (Jeanne Tripplehorn): Responsible for bringing technology to Constant Consumer magazine; her specific title is unclear, but she is in charge of budgets, a task that allows her to embezzle funds from the magazine.

Receptionist (Florina Rodov): Her brief appearance not only opens the film, but also introduces the news of the magazine’s downsizing.

Ted and Naomi (Doug Barron and Linda Powell): Editors at Constant Consumer magazine, they seem to function as a pair.

Virgini...