eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

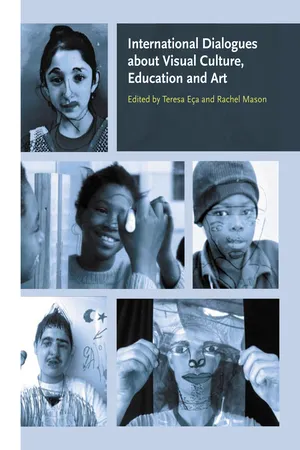

International Dialogues about Visual Culture, Education and Art

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 278 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

International Dialogues about Visual Culture, Education and Art

About this book

Although art is taught around the world, art education policies and practices vary widely—and the opportunities for teachers to exchange information are few. International Dialogues about Visual Culture, Education, and Art brings together diverse perspectives on teaching art to forge a comprehensive understanding of the challenges facing art educators in every country. This comprehensive, authoritative volume examines global views on education policy, discusses new trends in critical pedagogy, introduces new technologies available to educators, investigates community art projects, and shows how art education can be used for peace activism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access International Dialogues about Visual Culture, Education and Art by Teresa Eça, Rachel Mason, Teresa Eça,Rachel Mason, Rachael Mason, Teresa Eça in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CREATIVITY AND CULTURE: REDEFINING KNOWLEDGE THROUGH THE ARTS IN EDUCATION FOR THE LOCAL IN A GLOBALIZED WORLD

RMIT Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University, Australia

Abstract

This paper focuses on strategies for mobilizing culture and creativity through the arts in education and community settings. It reflects on a UNESCO regional meeting on the arts in education and presents three projects in the Pacific region that go some way towards meeting the challenges of globalization: the first is a research publication on art education; the second, involves scholarly exchanges that enhance cultural capacity-building and knowledge transfer; the third is a networked project lasting several years aimed at establishing a mode of regional thinking. Each project involves a range of practices that contribute to strengthening local and regional cultural knowledge in light of the very real challenges of a global knowledge economy. They play a part in mobilizing creativity and culture as a way of redefining knowledge and its transfer through the arts in education for the local in a globalized world.

Keywords

Arts education, Knowledge, UNESCO, South region, Identity, Culture

Cultural Identity and the Arts

While recognizing that globalization and internationalization are irreversible trends, support for these concepts should not lead to dominance or new forms of imperialism by major cultures and value systems from outside the region; rather, it is of vital importance that every effort should be taken to protect and promote the strengths of local cultures and intellectual and scholarly traditions.

(UNESCO 1998b, p. 57).

Reflecting on the role of arts practitioners and educators, Emmanuel Kasarhérou said, ‘the nation needs its artists, more than ever, to cast light on the path it has chosen’ (1999, p. 91). This statement refers to New Caledonia but it extends our attention beyond those particular shores. Artists and arts educators have a vital role to play in revealing conditions of the past, illuminating present politics and forecasting possible futures. Through the creative arts, stories are told as histories are interwoven and futures imagined. This paper argues that the arts work as creative knowledge practices to reflect and enhance diverse social systems, beliefs, epistemologies and economies. If the UNESCO priority of ‘mobilising the power of culture’ (1998a) is to be realized through the arts in education then artists and educators must take account of diverse and often competing political, economic and cultural histories, practices and epistemologies in the exchanges of a globalized world.

The need for cultural recognition and sustainability for the local has never been greater than in today’s global economy where knowledge is folded into the marketplace of mobility and transfer. If the arts represent a site of knowledge then they are already implicated in the political economy of knowledge transfer and social development, yet too often art and culture escape the attention of policy-makers at national and state levels and are positioned as frills on the side of the ‘real’ business of the economy. One way of challenging this situation is for leaders in the arts and cultural sectors to mobilize strategic research and action through education. The aim must be to bring the arts, culture and sustainable development together in policy frameworks. Culture per se can no longer be thought of as separate from the economy as was the case in industrial or colonial societies when principles and organizational structures were based in the hierarchical discourses of modernity. In a global age, where movements of people, finance, information and communications occur at an unprecedented rate, we face new architectonics of space, new logics of information and capital through which culture and the human subject are being organized. Reframed ideologies of centrality advance globally to blur the boundaries, both actual and assumed, of the local and specific. This global tendency serves to deterritorialize traditional spheres of place and identity, while at the same time territorializing in the name of global progress.

UNESCO Context

In the global context there is a need for strategic awareness and action to establish and strengthen local knowledge. To this end a UNESCO Regional Meeting for Experts in Art Education in the Pacific Region held in Fiji, in 2002, focused on regional perspectives in the Pacific through the arts in education. The Action Plan made specific recommendations to be taken up by delegates. In a poetic vein it urged the arts in education to resonate across the Pacific Ocean, like the frigate bird ‘Kasaqa’, as a symbol of commonality in the Pacific, a navigational spirit of creativity and culture. Symbols of commonality tend to carry with them an aspirational principle or call. This was no exception. Delegates were called to stay aloft as birds of navigation, to lead the consolidation and communication of creative arts in education as a way of strengthening cultural knowledge not only of the Pacific region, but also throughout the global world (Voi, 2003, pp. 6–7).

This call was both poetic and pragmatic. The frigate bird identifies not only the winds and currents between the scattered islands and lands of the Pacific region, but also like the arts, illuminates the spaces between different histories, patterns of habitation and knowledge systems. If ‘kasaqa’ provides us with a guide or beacon on our voyages across the oceans of knowledge, then as educational navigators we must keep our eyes on the political weather of globalization and currents of power. Recognition of the movements of power in globalization is an implicit necessity in UNESCO’s observation about the ‘dominance of new forms of imperialism by major cultures and value systems from outside the region’ (1998b).

The UNESCO Medium-Term strategy of 2002–2007 reflects the organization’s global role in forecasting the future and establishing strategies of capacity building for social, cultural and economic sustainability. The unifying theme of the UNESCO report (2002a, 31/C4), ‘Contributing to peace and human development in an era of globalization through education, the sciences, culture and communication’, acknowledges the emerging ethical challenges of globalization and the need to build new norms and principles to respond to them (2002a, p. 25).

As a way of mobilizing regional action in a global framework UNESCO brought together designated representatives of the creative arts in education in regional locations around the globe from 2001 to 2004 with the fundamental belief that artistic creativity and culture are the cornerstones of a safe and sustainable society. Five regional meetings were held in Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, Arab States, Pacific, Asia and Europe, concluding with the World Summit in Portugal in March 2006. The overall aim was to examine the contents and conditions of creativity and the arts in education throughout school and tertiary systems at each location, share best practice and consider pedagogical approaches to artistic education in the interests of integrating artistic programmes into national education systems (see UNESCO 2002b).

The Pacific meeting drew 40 specialists in arts education from the fields of drama, music, visual arts, dance, creative writing and storytelling, from twelve countries including Fiji, Tonga, Cook Islands, Western Samoa, Republic of Kiribati, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, Niue, Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. Delegates shared their perspectives, field experience and academic research on the arts in education and offered viewpoints that would provide the means for building on existing knowledge about the arts in education in the Pacific region. Issues under discussion were the paucity of public attention to the arts, their marginalization in education, problems of under-resourcing of teacher education in the arts, inequalities of participation, impact of tourism and erosion of cultural knowledge, the need for heritage protection and preservation, and a general lack of political attention to arts’ social role.

The Pacific Regional Meeting made recommendations for delegates to implement on their return to their various locations. These included:

(Wagner & Roundell 2003, p. 78)

The following presentation of three projects that took place between the 2002 Pacific Regional Meeting in Fiji and the 2006 UNESCO World Summit in Lisbon draws attention to a range of activities for the enhancement of cultural and scholarly capacities in southern regions. Each project plays a part in mobilizing the power of culture through the arts in education and works towards strengthening local and regional perspectives on arts and cultural knowledge.

Project One: The Arts in Education

In the early 2000s there was a sense of urgency about mobilizing leaders of the arts in education so as to bring together the voices of arts professionals in an educational research framework. A political focus in Aotearoa New Zealand at the time was a new national arts curriculum for primary and secondary schools, The Arts in the New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education 2000). The moment was right to proactively consider questions of curriculum and pedagogy in the arts within the context of globalizing knowledge frameworks. Building national curricula is crucial if official governmental support is to be put towards the arts in education, but equally important is the need for research and analysis of officially inscribed processes. This calls for a critical approach to arts, curriculum and pedagogy in institutional policies and practices.

In the case of Aotearoa New Zealand the implementation of the arts in education occurred in 2000. The implementation of The Arts in the New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education 2000) was the last phase in a seven-year process of setting up The New Zealand curriculum framework (Ministry of Education 1993). This was a national strategy that took the form of an outcome-driven system based on seven ‘essential learning areas’. Official attention to the arts fell way behind numeracy, literacy, science and technology, and a contentious situation arose when technology was introduced into the curriculum as a latecomer, with the effect of squeezing out time and attention for the arts (see Mansfield 2000; O’Neill 2004; Clark 2004; Grierson & Mansfield 2004). Unlike ‘technology’ as a curriculum subject, the arts involve more than skills and technological thinking. The arts respond to political, cultural and technological changes in local and global communities and in the process they tend to escape easy categorization.

The organizers of this research project on the arts in education opened questions of categorization, pedagogy and curriculum in the arts to critical scrutiny.1 The outcome was the first book of its kind in New Zealand about the arts curriculum (Grierson & Mansfield 2003). Contributions were solicited from leading academics in visual arts, music, dance, drama, design and curriculum theory. They were asked to consider what it means to be critical in arts education today (see Peters 2003).2

Knowledge in and of the arts can be confined to a safe realm of aesthetic and formalist concerns apparently devoid of political contexts, or it might take the form of critically engaged practice whereby contextual enquiry exposes the social, cultural and political terrain within which it is situated. The writers placed the arts and curriculum policy in the context of political and social conditions and coordinates of new technologies, economic and cultural globalization, and intersections of knowledge with the economy. This political framing was foregrounded by the educational theorist Michael Peters (2003):

[Q]uestions of national and cultural identity loom large under the impact of an economic and cultural globalisation that threaten to displace many historical coordinates we previously took for granted; and a new kind of imperialism – one ostensibly compatible with human rights and cosmopolitan values – is being advocated by advisors to Western leaders as a foreign policy basis aimed at ‘regime change’ of so-called rogue states. Aotearoa New Zealand is also at a critical point in coming to terms with its own colonial past in addressing historic Maori grievances, its constitutional ties with Britain and its relationship with the United States. (pp. 9–10)

The implication of this line of analysis is that where the official rhetoric of government policy becomes the normalized language of educational practice in the arts, it follows that educators need to advance a political understanding of arts discourses in relation to policy and globalization. The de-regulation of the New Zealand economy has had the effect of opening the country to the vagaries of the market economy with foreign investment and ownership of public assets, bi-lateral agreements, global trade pacts and international competition for goods and services, which, as Peters (2003, p. 10) points out, include health and education that were once part of a protected public domain. The arts are not immune from such political moves and influences. Their material forms and social functions inevitably respond to changing social conditions. Thus, arts educators must be fully aware of the social and political contexts of arts and culture. Then they can position the arts as significant sites of knowledge that operate in partnership with economic development and sustainability in a globalized world marked by an escalating pace of knowledge transfer.

Artists reflect, intervene and relate to the world in ways that bring it into the line of sight. If as Emmanuel Kasarhérou (1999, p. 91) stated, artists are needed more than ever now to cast a light on the path a nation has chosen, then the role of educators in the creative field must be to ensure learners are equipped with knowledge of the nation and its political directions as well as of art-making, aesthetics, technological skills and art knowledge. This can be done only with wider knowledge of the local, regional and global spheres so that ‘the nation’s path’ becomes visible in its whole context.

Project Two: Nga waka and Te whakatere

The second project exemplifies how national educational conferences can make local and regional paths visible. Nga waka (2003) and Te whakatere: Navigating with the arts in the Pacific (2005) were two biennial conferences convened by the Aotearoa New Zealand Association of Art Educators (ANZAAE). They positioned the cultural aspects of art at the forefront of educational concerns. If we are to think and act regionally, epistemological and social differences inherent in the region must be understood via cultural, artistic, linguistic, material and textual practices. The voices and languages of diverse cultural histories and indigenous narratives must be heard, just as the persistence of historically dominant constructions of the Pacific through western epistemologies must be acknowledged. Thematically both conferences conceptualized ‘navigations’ as an historically appropriate symbol for the processes of recognition and repositioning of cultural identity.

Nga waka unpacked the WAKA, canoe, letter by letter, in four dimensions of art education with reference to twenty-first-century conditions. W-A-K-A: W–Witnessing Biculturalism; A–Activating Technologies; K–Knowing Art Educations; A–Acclaiming Asia Pacific. Through rigorous scholarship, concepts of voyaging found form across epistemological space and time in the worlds of art education. Diverse modes of scholarship surfaced in re-thinking the arts in the context of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface: The Politics of International Art Education

- Introduction

- PART 1: GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES

- PART 2: CRITICAL PEDAGOGY

- PART 3: NEW TECHNOLOGIES

- PART 4: COMMUNITY AND ENVIRONMENT

- PART 5: ART EDUCATION FOR PEACE

- POSTSCRIPT: CHILDREN'S DRAWINGS

- About the Contributors

- Index