eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

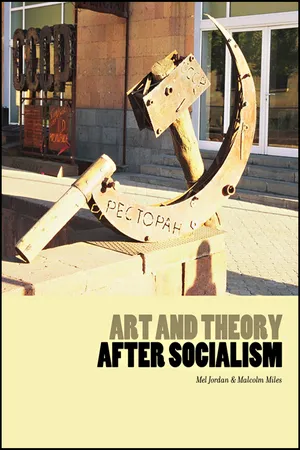

Art and Theory After Socialism

Art and Theory After Socialism

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 125 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Art and Theory After Socialism

Art and Theory After Socialism

About this book

Art, theory, and criticism faced radical new challenges after the end of the cold war. Art and Theory After Socialism investigates what happens when theories of art from the former East and the former West collide, parsing the work of former Soviet bloc artists alongside that of their western counterparts. Mel Jordan and Malcolm Miles conclude that the dreams promised by capitalism have not been delivered in Eastern Europe, and likewise, the democratic liberation of the West has fallen prey to global conflict and high-risk situations. This volume is a revolutionary take on the overlap of art and everyday life in a post–cold war world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Art and Theory After Socialism by Mel Jordan, Malcolm Miles, Mel Jordan,Malcolm Miles, Mel Jordan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

FROM SHAMED TO FAMED – THE TRANSITION OF A FORMER EASTERN GERMAN ARTS ACADEMY TO THE TALENT HOTBED OF A CONTEMPORARY PAINTERS’ SCHOOL. THE ‘HOCHSCHULE FÜR GRAFIK UND BUCHKUNST’, LEIPZIG

A decade and a half after the fall of the Berlin Wall the output of cultural heritage and theoretical production in the two former German states needs to be critically revised. During the early times of governmental and societal change and reorganization, Eastern German frameworks were generally regarded as politically unacceptable and immoral whilst Western German cultural politics a priori claimed to be just and politically correct having been created within an essentially liberal and democratic system.

While there are no doubts about the totalitarian nature of the former GDR per se, the developments of the past years have proven that such polarized dichotomies are not tenable. Some of the attitudes and modes of artistic production, specifically in the East, turned out to be nonetheless valid, adding a surplus value to contemporary debates and developments. As a result, western theoreticians, critics and artists alike needed to accept that their belief system had to be critically re-examined. In addition, the tasks that governments, cities, districts, schools and individuals had to face were so manifold that theoretical blueprint planning was simply impossible. Many changes happened organically or were brought about by individuals who exposed specific situations and set about the process of change by refusing to work under conditions which were not yet clarified or reorganized, or by proposing different and new approaches.

The developments within the cultural scene are evident when considering the art academies, as the institutional setting allows an analysis of the kinds of changes being made including their purpose and timing. The former Eastern German state only maintained four main centres for artistic training: Berlin, Dresden, Halle and Leipzig. The latter proves a useful example as it is the one academy which is currently well discussed within Germany and abroad, due to the success of the New Leipzig School of Painting, a heterogeneous painters’ group closely tied to the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst (HGB), Academy of Visual Arts Leipzig. The prominence the artists are currently receiving can partially be attributed to the traditional painter’s training at the HGB which follows curricula different from the majority of other art academies in unified Germany. Although this study will take into account the situation of the entire HGB, it must be clarified that changes happened in very different ways for the four different departments: namely photography, book art and graphic design, media art (founded in 1993) and painting and graphics. I will be focusing attention on the developments in the latter department. In the following chapter, I will discuss how theories, curricula and academic structures were altered or accepted in transition after 1989 and what the specificities of the HGB are today.

In order to discuss these ideas, the historical background of the academy needs to be clarified. This exploration will include brief explanations of cultural policy made by the former Eastern authorities at specific times, as developments within the arts were closely monitored and even influenced by the Eastern German government. Furthermore, the term ‘Leipziger Schule’, Leipzig School, which dates as far back as the early 1950s, shall be explained. Finally, an evaluation will be made of how the bringing together of two diametrically different political systems has worked out at the level of artistic production looking at its successes and failures.

Brief Historical Overview

Founded in 1764, the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst in Leipzig by the 1920s had become one of the most important art schools in the country. Renown for its letterpress and printing faculty, the school attracted students from all over the country. All this came to a halt during the Nazi regime and the academy had to be re-established in 1945. A quick succession of two headmasters defined the formative years of the school in the about-to-be-founded German Democratic Republic: Walter Tiemann, who had been headmaster since 1920, and who was reinstated as a commissioned director in 1946, followed by Kurt Massloff, who became headmaster in 1946 and remained in this post until 1958. Massloff was a highly politically active anti-fascist whose goal was to turn the school into a socialist visual art school where the concept of realism (as developed by Andrei Zhdanov) was to be taught and produced without any inquiry into, or consideration of, other art forms. This development turned into the harsh and highly politically charged ‘Formalism-Debate’ which led, in 1951, to the dismissal of any member of the GDR community of artists and teachers who did not conform to the state-affirmed version of realism (Hübscher 1989; Gillen 2005; Goeschen 2001; Thomas 2002; Schuhmann 1996; Vierneisel 1996). Any continuation of the art forms of the early twentieth century was regarded as a deliberate separation from the socialist people, portrayed as formalistic and condemned as the remains of a bourgeois attitude. Therefore, teaching focused on the imitation of classical and traditionalist styles of the nineteenth century. This concept paralyzed the entire development of art and literature for a long time in the GDR, specifically because the ‘humanistic cause, which had become an issue for many artists through the acquisition of important artistic tendencies of the 20th century were questioned in their moral integrity and artistic substance’ (Pachnike 1989:16). It was a step back towards traditions of the past, where the artist was trained to fulfil the wishes of the patron who commissioned a painting, but no individual artistic education took place. Werner Mittenzwei describes the situation as follows: ‘The criterion for realism and popularity was not its testing as a means to the political class battle and in the cultural practice, but to what extent the new socialist art works followed the traditional norms and laws’ (Mittenzwei in Pachnike 1989: 16). The dismissal of the expressionist artist Max Schwimmer in 1951, among other faculty members, led to the voluntary withdrawal of two of his students in protest against the unfair treatment of their professor(s). One of them was Bernhard Heisig, who was later to become one of the most influential headmasters. Quite a few, even among the faculty, were extremely dissatisfied with the situation:

The new fact is that we are opening our mouths and have stopped allowing them to step over us. Doing this we have certainly already accomplished quite a bit for our situation here. On the other hand I am certainly aware that still an incredible amount remains to be done. Our faculty is still a quantitatively large pile but qualitatively quite thin. It is not easy but we’ll keep on banging the drums. Either we accomplish a situation in which it is possible to work at the academy or they kick us out (Meyer-Foreyt in Blume 2003: 293).

Some tension was lifted from the ‘Formalism-Debate’ situation in 1954 when the state commission for art, which was directly linked to the Soviet forces, was disbanded and the ministry for culture was founded. However, cultural affairs from 1959 onwards were treated along the guidelines of what became known as the Bitterfelder Weg (Bitterfeld Path).

The first Bitterfeld Conference, in April 1959, was organized by the government and brought together authors and working people with an active interest in writing. It took place in a chemical factory in Bitterfeld. The conference set the course of how cultural affairs and specifically painting had to be dealt with in order to serve the socialist cause. The aim was to bring together ‘art and life’ in order to blur the lines between professional art production and the working-person’s life. Three main goals were to be reached: a close-to-life depiction of the working world and cultural influence in the life of workers according to the party’s ideas; the early recognition of talent among the workers in order to educate them to become faithful interpreters of the socialist image of the people; and the mixing of academically taught artists with workers in order to dilute the intellectuality of the former and to introduce them to the real worker’s life (Thomas 1980: 55–58).

The programme was, as would be expected, unsuccessful and the motto and resulting programme of the second Bitterfeld Conference in 1964, ‘The Arrival of the GDR in the Socialist Everyday’, addressed itself once again exclusively to professional artists (Thomas 1980: 55–58).

The artistic atmosphere in the HGB firstly became more liberal in the department of letterpress and bookbinding when Albert Kapr was appointed head of the department and, in 1959, also headmaster of the school. An even more open and critical discussion about Socialist Realism and how it could be applied politically was introduced when Bernhard Heisig, a former student, became headmaster in 1961. His aim was to give academy students the possibility to find their own means of expression, including critical approaches, to serve the socialist cause as artists. The same year he also introduced the first independent painting class, although director König stated explicitly in 1964, ‘The faculty holds the opinion that studying painting can be a positive influence on the use of colour in the graphic arts’ (Schiller 1964: 38). Judging from this quote, it becomes clear that painting had to establish itself slowly in order to become an equally accepted subject. It would, however, later receive the status of a main discipline at the Leipzig art academy.

The following years, during which time the term ‘Leipziger Schule’ was coined, were strongly shaped by the work and exhibitions of the three most well-known HGB artists: Werner Tübke, Wolfgang Mattheuer and Bernhard Heisig. The artist Willi Sitte, who held a professorship at the arts academy Burg Giebichtenstein in Halle, is often included in the group. Their interpretation of Socialist Realism was not only very personal, it also introduced the ‘simultaneous image’, Simultanbild, which lifted the traditional unity of space, time and action within a painting, as well as using montage and collage. Furthermore, the logical course of a painting was not determined by the narrative anymore, but more by the stream of consciousness of the artist, a process which included irrational elements. They were able to overcome the harsh criticism they received by convincing the public of the meaningful use of these elements and the high artistic quality of their paintings. In addition, for the first time, they claimed to treat the public as an equal in dialogue, rather than an audience that had to be educated as the positioning of the artist within the communist system suggested. Heisig formulates this on the V. Congress of Visual Artists 1964 as follows: ‘In order to really establish a contact to the viewer, an art is called for, which must, in any case, be interesting as well as interested, but this can only be triggered by a type of art which challenges the viewer mentally, which provokes, annoys and attacks’ (Heisig in Pachnike 1989: 20). Other specific traits of the Leipzig School as formulated by Werner Tübke (Hartleb 1989: 44) were a strong tie to realistic painterly traditions, among them Verism and New Objectivity, the use of allegory and ties to the literary. Commentaries on everyday life conditions bearing subliminal political criticism can be added to this list (Hartleb 1989: 43). Politicization in the service of communism was strongly encouraged, yet hints of doubt or even disagreement strictly forbidden. Thus, any such claims had to be made by smartly avoiding censorship. Encouraged by Heisig, who strongly shaped the school with his decisive personality and opinion about the responsibilities of an arts academy, a climate was created in which debates and discussions, even about political topics, were possible to a certain extent. Quoting from a speech Heisig gave at the VIII. Congress of Visual Artists of the GDR 1978:

Acknowledging that the existence of an artist is only one in a long succession, with many preceding artists and many to follow and not for the first time I am realizing that our historical, or, if this provocative term is uncomfortable for you, our feeling for larger contexts is deeply disturbed. I would […] like to measure this with something which I want to call historical conscience (Geschichtsbewußtsein). […] However I do not only believe this because as a headmaster and head of a painting class of the Leipzig School for Visual Arts I have been experiencing, how little younger colleagues [Heisig calls his students colleagues as well] know where they are coming from and how badly they are fed with what is superficially dismissed as “history”, but because a process of ‘holding on to oneself’ is more and more becoming the norm. The great internalization, the personal, the too personal is setting in. The lack of historical conscience, of large themes and topics can neither be balanced out by a visit of a factory nor by a work placement in a Kollektiv.[…] No people can live without its past, there is no nation and of course there are no visual arts, no architecture and no cities. A people without its past is art-incapable. Nobody shall claim that Picasso, Klee and Beckmann were not aware of this. The old ones knew this in any case. Maybe this will be a reason and I am not saying it is the only reason to create something, to start dealing with larger topics again. Something that will make it possible to shift the personal out of the centre of attention, to reorder from a new point of view and to strengthen the artistic means. Maybe this way we will not have to quarrel anymore if, for the artist, the human figure and her points of reference are, if not the measure then at least a measure of things (Kober 1981: 192).

A further example of this is a memo from 1967 in the form of a requested report from the headmaster, in which the faculty members had to justify their own position in relation to the political education of the students as well as: (1) the results they could achieve; (2) which obstacles might harm political education; (3) and how the teachers thought they could contribute (to the best of their knowledge) to the political education of the students, which would facilitate their emergence as supporters of the state (Kapr 1967). While the reports from all other faculty members are clearly very formal, affirmative answers to their own political positions, as well as to their teaching and actions, Bernhard Heisig’s report is the only one in which quite harshly formulated criticism becomes obvious. He states that the work of an artist a priori necessitates a very strong political stand, and that such issues are discussed and debated on an everyday basis in his classes. In his answer to the third question, Heisig criticizes the fact that most obstacles are coming from within the HGB itself:

We are lacking the open discussion within the faculty and resulting obviously also among the students. The call for opinion debates fails due to an exaggerated caution and the fear of possibly saying something wrong and therefore to a personal disadvantage. I cannot welcome this, but understand it. I realize for myself that the blame for interest and active participation in discussions and touching of so called “hot irons” [controversial discussion topics] is always with the one who engages himself in the discussion. Consequently, one part of the faculty, similar to most of the students, takes a neutral point of view in any discussion in order not to have to fear personal disadvantages. In this school obviously the maxim rules, that who does not act at all will not risk making faults (Heisig 1967).

Neo Rauch, an artist who studied during the last years of Heisig’s term as a headmaster and who became his Meisterschüler (Master Student) in 1986, confirms in an interview: ‘He would give us all the space we wanted, we were able to experiment, to debate; complete freedom within the walls of the academy. He said: “Do whatever you want, as long as you stand there next to me on the 1st of May when we all have to parade.” And this is what we did’ (Gerlach 2005).

The rigid political guidelines artistic production had to follow in the GDR were gradually loosened, so that in the late 1970s more progressive developments were able to take place. One example is the Experimentalklasse (Class for Experimental Art), a unique class at the time, for which Bernhard Heisig appointed Hartwig Eberbach as its first teacher in 1979.

The former Heisig student Arno Rink, who had worked as an assistant teacher since 1972, became headmaster in 1987 until 1994; thus, the years of turmoil and change after November 1989 entirely fell into his term. A strong believer in the realist tradition and in art as a medium inherently connected and needed for societal processes, Rink continued the heritage of his predecessor, stating in a catalogue published at the occasion of the 225th anniversary of the academy:

If realism exists […] it will more and more show defects and disturbances in the material of the paintings as well as sorrow about losses, it will refocus onto the private, which again reflects the social environment. If society has asked the artist to be actively involved in public matters and supported him in that position, then that has to happen all the way and the artist must also be allowed to utter criticism,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. From Shamed to Famed – The Transition of a Former Eastern German Arts Academy to the Talent Hotbed of a Contemporary Painters’ School. The Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst, Leipzig

- Chapter 2. Attacking Objectification: Jerzy Bere in Dialogue with Marcel Duchamp

- Chapter 3. On the Ruins of a Utopia: Armenian Avant-Garde and the Group Act

- Chapter 4. Art Communities, Public Spaces and Collective Actions in Armenian Contemporary Art

- Chapter 5. Appropriating the Ex-Cold War

- Chapter 6. The End of an Idea: On Art, Horizons and the Post-Socialist Condition

- Chapter 7. Exploring Critical and Political Art in the United Kingdom and Serbia

- Chapter 8. Other Landscapes (for Weimar, Goethe and Schiller)

- Chapter 9. The Ecology of Post-Socialism and the Implications of Sustainability for Contemporary Art

- Chapter 10. Functions, Functionalism and Functionlessness: On the Social Function of Public Art after Modernism