- 156 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

DRAWING WITH PURPOSE IN POLITICS

Dave Brown is the political cartoonist for The Independent. He studied Fine Art at Leeds University, graduating in 1980. Before becoming a cartoonist he worked as a motorcycle courier and was the drummer in a punk band. In 1989 he won the Sunday Times Political Cartoon Competition and subsequently worked for a number of British newspapers and magazines before taking up a regular post on The Independent in 1996. In 2006 his cartoon Venus Envy was voted Political Cartoon of the Year, an award he had also received in 2003. In 2004 he was named Political Cartoonist of the Year by both the Political Cartoon Society and the Cartoon Art Trust. In 2007 his book Rogues’ Gallery, a collection of political cartoons pastiching famous paintings, was published.

Dave Brown elaborates on his drawing as a political cartoonist and as a ‘visual journalist’. He discusses the value and potency of a personal political point of view on the news of the day and how he is motivated by contemporary politics in his work. Working as a highly motivated political commentator, he sees his work operating as anti-establishment, ‘to prick the pomposity of the so-called great and the good’, though all within the parameters of the newspaper’s philosophy. Trusting his personal sense of humour is part and parcel of his work, and keeping his satirical viewpoint to the fore is of equal importance in his completed drawings.

The purpose in his work is clear and expressed with agility in this essay, which also outlines his daily routine in working towards the everpresent deadline, taking into account how the news can change during the course of each twenty four hours. Five mornings each week with a blank piece of paper, after a brief discussion with the Comment Page editor, Dave Brown sketches from television, ruminates on quotations from various current scenarios and other sources to work towards meeting the demands of a daily broadsheet, and the position of his drawings next to the editorial leader. The sixth day, Saturday, he produces a cartoon for the ongoing series ‘Rogues Gallery’. His bold drawings bring us clear messages and hold a prominence, exposure and perhaps influence that few artists ever achieve.

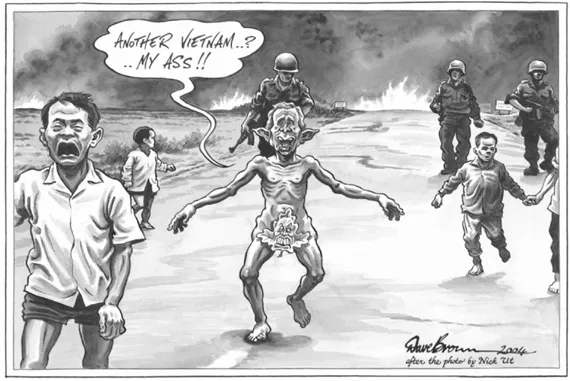

Another Vietnam.

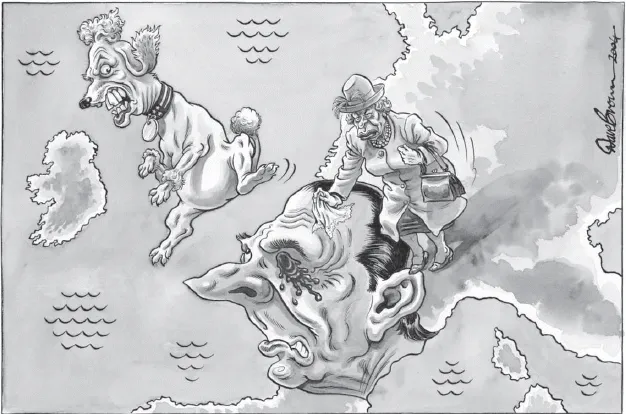

Entente Cordiale.

Every morning, six days a week, I sit down in my studio with a blank sheet of paper on the drawing board in front of me. By the end of the afternoon I must have transformed it into a finished piece of artwork, scanned it and e-mailed it to an office in London’s docklands. The next morning you might see it at your breakfast table or on your train to work. That is if you still read a newspaper and if that paper is The Independent.

I am the paper’s political cartoonist and on the newspaper’s editorial pages I create those grotesque images of our own dear Prime Minister and the other leaders who govern us. Tomorrow of course they’ll be wrapping your fish and chips (the grotesque images, not the leaders unfortunately), or perhaps – you being a conscientious Independent reader – in the recycling bin.

A rather ephemeral art then, looked at for a few seconds perhaps before being discarded. So what’s the point? What’s the purpose? Most national newspapers still recognize the need to employ a cartoonist (though worryingly some recently have decided they can do without); they understand that we help to enliven their acres of grey text. But what else are we good for?

My work still sits in the traditional position for the political cartoon, on the leader page. This is the page where the columns have no bye lines, but propound the paper’s position on the issues of the day. Yet my cartoon neither illustrates those leader columns, nor expresses a view dictated to me by the paper. Rather it sits apart, it bears my signature; it is, if you will, ‘all my own work’. My position is more like that of columnists also found on the editorial pages, expressing a personal point of view on the news. The political cartoonist is a visual journalist aiming to persuade you to his or her (almost invariably ‘his’) point with a drawn satire.

Once in an interview I was asked ’Do you draw with the idea, hope or intent that you might be impacting on public opinion?’ This was cunningly followed by the question: ’Do you feel that you have had an impact on public opinion over the years?’

Now of course I’d love it if my coruscating wit could strip the scales from readers’ eyes so that they embraced my personal political vision; however I’m not so deluded. A cartoon won’t change the world. I doubt whether it’s likely to effect a Damascene conversion in a single reader. But in a system where most of us can only tell our leaders what we think of them every five years or so, I’m in the wonderful position of being able to metaphorically poke them eye with a sharp pen every day.

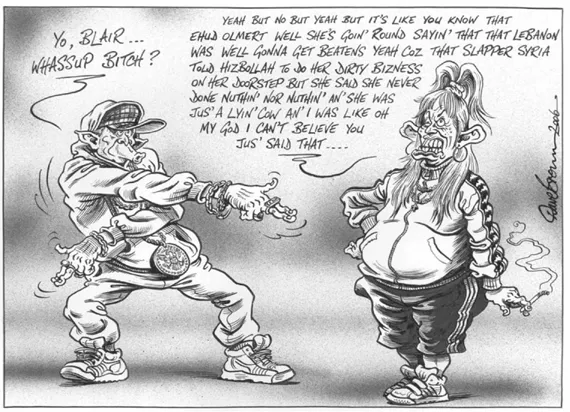

Blair.

Does this hurt them? Not as much as one would hope; mostly politicians ignore cartoons, some infuriatingly draw the sting by asking to buy the original (after all there is only one thing worse if you are a politician than being cartooned, and that’s not being cartooned).

However, occasionally your ridicule does manage to rankle. I tend not to consort with the enemy but I was once introduced to a cabinet minister at a party who, on discovering who I was, complained about how I’d been drawing him recently. Needless to say, what had been a one-off gag became a regular feature of my caricatures of him, and this felt like some sort of badge of success, purpose paying off.

The cartoon is an art form with an amazingly broad language. It can combine images and words; static and two dimensional, yet it can convey movement, time and sound. Figurative, and to an extent realist, it can create an extraordinary range of fabulous characters and surreal settings that would cost Hollywood millions, all with little more than pen and ink.

Political cartoonists in particular draw upon a wide range of references from everyday life, popular culture and high art to subvert and make their point. A cartoon can often be (deceptively) simple and economical in its line. However, the space historically afforded to the political cartoon in British newspapers has led to a tradition of often fine draughtsmanship.

And the political cartoonist has to have something to say; like the gag cartoonist, we want to make you laugh, but with a purpose. There’s no point to a political cartoonist without a strong political philosophy. There is always the need to challenge the reader to an extent, and not simply reflect their own views back at them (though of course editors rarely employ cartoonists who are completely antithetical to their papers’ views).

Interestingly, the majority of the political cartoonists come from the left of the political spectrum and while there have been some successful right wing cartoonists, the profession by its nature seems anti-establishment; the desire is always to poke fun at those who hold power over us, to prick the pomposity of the so-called great and the good.

I have drawn since I was a child and was always fascinated with comic books, drawing my own characters and stories from a very early age. At secondary school I discovered that caricaturing the teacher was more amusing than staring out of the window, and had the added bonus of concentrating my view in the correct direction whilst my pen could appear to move diligently across my exercise book.

I studied Fine Art at university and then taught art for three years, all the time contributing cartoons to student and later Trade Union publications. I abandoned teaching to paint full time but had to support myself with a variety of other work from graphic and theatre design to working as a motorcycle courier. It took some time to realize that what had been an amusing side line could be a full-time career, winning the Sunday Times Political Cartoon Competition in 1989 was the catalyst.

Croquet.

In the early years of my professional career I drew cartoons, strips and illustrations for a range of papers and magazines on a host of subjects, but it was always the editorial political cartoon that most interested me. Politics and Art have always been inextricably linked in my practice, whether as a painter, designer or cartoonist.

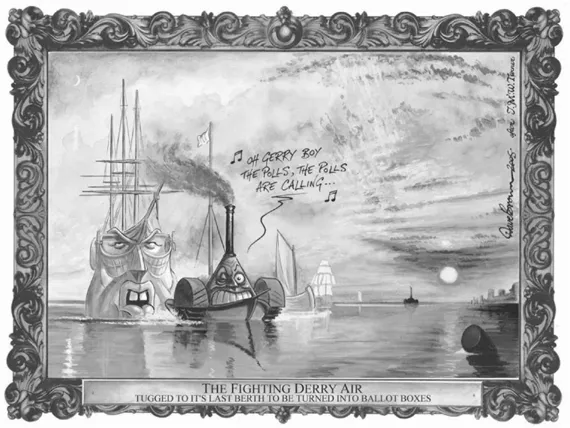

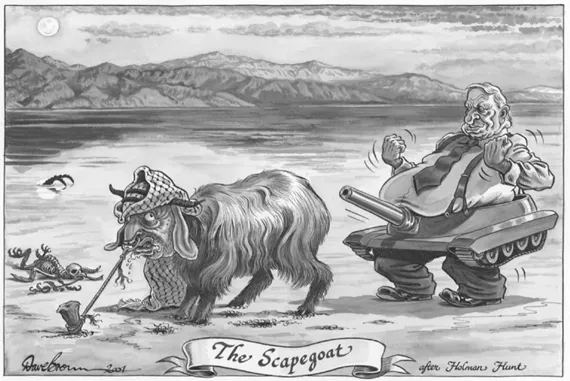

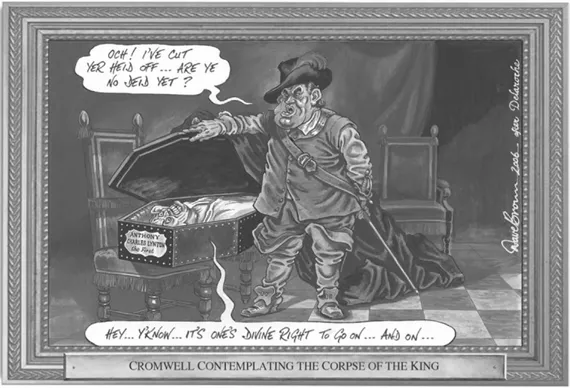

Now I work almost exclusively for The Independent, drawing five weekday cartoons where topicality is essential, and a feature called ’Rogues’ Gallery‘ for the Saturday paper which is a satire on one of the themes of the week in the form of a parody of a famous painting.

I wake up as the Radio 4 Today programme comes on my alarm, and the first part of my day is spent with one ear glued to the radio while leafing through a pile of the morning papers, occasionally raising an eye to watch the TV rolling news stations. The idea of absorbing so much news is not simply to see what stories are playing big that day but to hear a wide a range of comment and interpretation, and possibly a telling quote from an interview, which might spark an idea. Also I have to be aware of what aspects of a story are being picked up by the media. I may personally want to focus on one particular aspect of a story, and I have to know that it will be familiar to the readers/viewers of my cartoon.

After 10.00am I call the paper and have a brief conversation with the Comment Page editor, to establish what story we think I should concentrate on. Some mornings there will be one that stands out and our conversation is over in seconds, on other days we may come up with a shortlist of equally valid topics, and it will be left to me to choose one which fires me up the most.

I then sit down with that blank sheet of paper develop an idea. This isn’t really a ‘light bulb over the head’ moment so much as a set of mechanical work processes. There may be a quote I’ve already heard, or an image I’ve seen that will set the ball rolling. Modern politics is obviously very image-conscious, and many policy statements are made in set piece photo-op locations. Here the 24 hour news stations are very useful, and I may sit sketching in front of the telly to get the look of something happening that day, but I am also watching for anything untoward which may have escaped the spin doctor’s choreographed news management.

Recently Blair was giving a speech at a community centre and stopped on his way into the building under a sign proclaiming ‘The Folk Hall’; it was a cartoon begging to be drawn, with the letters O, L and H mysteriously going missing.

Derry Air.

Scapegoat.

Cromwell.

When events don’t offer such gifts and the idea isn’t quite sparking, there are usually a few well-worn techniques you can rub together to get the fires burning: writing lists of aspects of a story, and utilizing word association to create new parallel lists; anything that creates unusual or surreal juxtapositions. Or visually, the actual stricture of working up a caricature, particularly of drawing someone for the first time, might suggest a likeness to some animal or object which provides the clue to depicting them. Usually in all this you’ll have some sort of goal in mind; as I’ve said you’ve got to have a point you want to make, a purpose to the drawing. However sometimes, rather than working to find an image to express that point, you hit upon an apparently irrelevant image which nevertheless somehow grips in its absurdity. It somehow works as an image, but you’re not sure what it means! Rather than dismiss it, the skill here is in spotting how it can be made relevant. Often these turn out to produce the best cartoons. I have the theory (completely lacking in any scientific rationale) that some images bypass logic to appeal to some more primitive part of the brain.

Once the idea has coalesced I rough it out quickly in pencil and fax it to the paper for approval. Sometimes I might want to check out if an idea ‘works’ or if someone else finds it funny; however, mostly it’s best to trust your own sense of humour. Show the cartoon to five different people and you’ll get five different responses. From the paper’s point of view, the approval process is more to ensure that I haven’t d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Drawing with Purpose in Politics

- Chapter 2: Drawing Archaeology

- Chapter 3: Drawing with Science

- Chapter 4: Reflection on Time Spent Drawing: Towards Animation

- Chapter 5: Drawing: A Tool for Designers

- Chapter 6: None, Yet Many Purposes in My Works

- Chapter 7: Information without Language

- Chapter 8: Landscape – Drawing – Drawing – Landscape

- Chapter 9: Hew Locke on Drawing and Sculpture

- Chapter 10: Drawing is a Way of Reasoning on Paper

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Drawing by Leo Duff, Phil Sawdon, Leo Duff,Phil Sawdon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art général. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.