![]()

Part I

Theorising about Thinking and Drawing: The Limitations of Theory-led Research to the Practitioner

![]()

Chapter 1

About Thinking and Drawing – The Process Rather than the Artefact

The supreme misfortune is when theory outstrips Performance.

Leonardo da Vinci

How do I think as I draw?

The question that motivated this investigation was a question I asked myself as a practitioner. Although I could not necessarily articulate it at the time, a major part of what sparked my interest lay in finding out how this question could be answered. All I knew to start with was that it was important to ensure that my findings would be meaningful to what occurred in practice, because approaching the activity of drawing through abstract theory often appeared hollow when it came to the real thing.

Putting these initial ideas into words, I initially recorded my aim as being to investigate ‘the role of drawing in the creative process and its relationship to thinking’. My interests were however more generally concerned with:

• Drawing as a thinking process.

• Conscious and unconscious aspects of the process.

• The notion that thinking might not just involve knowing with the head, but thinking through the body.

The most obvious way of tackling these issues might have been to head to the studio, but before I could do this I came face to face with perhaps two of the most substantial issues facing anyone setting out on a path like this. The first was ‘how is research through practice done?’ and the second was ‘what distinguishes art research from simply being ‘art’?’

I could not assume that I would find answers to these questions by isolating myself in the studio. It became evident that I would have to do some theoretical ground-work to discover how the drawing/thinking relationship had been accounted for by others, and the means by which this had been accomplished. Without being fully aware of the basis for its use, simply choosing drawing as a method of investigation would not necessarily provide a deeper understanding of the situation.

Why drawing?

Drawing as a medium through which to investigate creative thinking is pertinent because of the immediacy of the activity – there is little in the medium that intervenes between the artist and the marks that are made. I read that, ‘drawings are seen as a unique form of access to the thoughts of the people who make them. Indeed they are simply treated as thoughts’ (Wigley in De Zegher & Wigley 2001: 29).

There appears to be a consensus amongst commentators that ‘drawing turns the creative mind to expose its workings’ (Hill 1966: 4). Some define the activity as a cognitive tool to facilitate and assimilate information (Tversky 1999). Others interpret drawing more personally as being akin to the conflict between signature and outcome of intelligence (Godfrey 1980; Chhatralia in Kingston 2003). Yet others emphasise how drawing plays a developmental role in the process of thinking through ‘an interplay between the functions of seeing and knowing’ (Rawson 1979: 7). Whilst many of these were the views of practitioners, they were still in effect the opinions of others. I was left wondering how I might have some understanding of these findings for myself, and began by reviewing a number of contemporary theoretical assumptions about the drawing/thinking relationship.

Style and thinking

Perhaps the most easily assumed visual connection between drawing and thinking is the possibility that a drawing’s style can reveal the nature of the thinking processes that made it. In other words, style is analogous to mode of thinking and, by extension, its purpose (Thompson 1969).

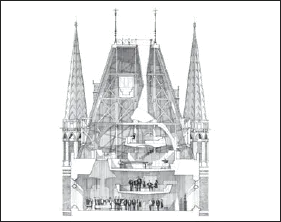

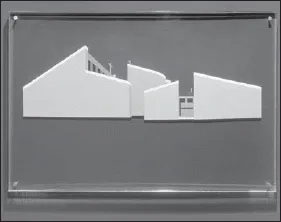

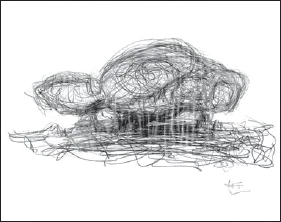

It is often assumed that cool or analytical drawings which are linear, hard-edged and precise in their mark-making are the outcome of pre-determined and conventional cognitive processes (Rawson 1969; Thompson 1969). For instance, the plan (Fig. 3a) section and elevation drawings used in the architectural process rely on their ability to operate like a language that is understood by a wide range of disciplines. Warm or intuitive drawings on the other hand suggest informal, gestural and experimental attitudes to mark-making (Fig. 3d). They appear to involve processes with no a priori or forward-thinking cognitive strategy, where aims are revealed only on completion of the drawing (Perry 1992).

These assumptions have been challenged on the basis that their use very much depends upon the social and cultural context in which drawing is used (Robbins 1994). I also noticed how a variety of practitioners often use drawing styles out of context; in fact, some practitioners actively play with these assumptions. I investigated the grey area in which architects such as Kiesler (Fig. 3c) rely on a range of non-technical drawing conventions for conceptual architectural projects, and where artists such as Paterson (Fig. 3b) explore technical drawing conventions more traditionally associated with architectural drawings to make social comments. In these examples I found that style was simply a variable that could be manipulated to various expressive effects.

(a) Alan Dunlop: Elevation of St. Pancras.

(b) Toby Paterson: Suburban Church.

(c) Frederick Kiesler: Endless House Sketch. © Austrian Frederick & Lillian Kiesler Private Foundation, Vienna.

(d) Claude Heath: Head 103.

Fig. 3: Examples of conventional and gestural mark-making in drawings in architecture and fine art.

In addition to this, the notion that style is analogous to thinking implies that a practitioner knows in advance what he or she is doing and can choose to use a particular style accordingly. However, this idea fails to take into account how, in practice, ideas often appear to emerge as the activity progresses. I began to question whether it was actually possible to carry out a totally pre-determined drawing without the process of making it changing one’s plans as one went along. Could it be the case that the act of making would always interfere to change one’s intentional or logical reasoning?

Moreover, simply identifying a type of thinking by reference to a visual style does not adequately explain the complexities surrounding the bodily processes required for different types of mark-making. I found it possible, for instance, to make gestural marks quite intentionally and vice versa. This allowed me to see the danger of making assumptions about what happens during the making of a drawing by reference solely to the outcome. As a result, I re-focussed my interest from ‘the drawing as an artefact’ to the process that produced it.

This also had the effect of making me appreciate that drawing is much more than simply a visual issue (although it was frequently described as being a visual thinking process). If this were the case, investigating how thinking was bound up in the process of drawing would need to rely on more than just ‘seeing’. Halsall has a point in saying that:

Any mode of analysis which limits itself to one sense alone will be a floored account of experience. This is because it does not recognise the multi-sensory nature of that experience and as a result will not be a satisfactory basis for a thorough historical account.

(Halsall 2004: 21)

It would therefore be necessary to find a method of investigation that would encompass performative as well as visual aspects to the activity.

Creative thinking theories

With my focus now on asking how a drawing is done rather than what a drawing is, I looked at how others had accounted for creative process. There was no section on the shelves in the library dedicated to ‘the artist’s creative process as written by the artist’ – what accounts I did find by artists were usually couched in letters or conversations. Much more was written about creative thinking by psychologists.

These texts appear relevant because they talk about processes involving invention, innovation and evolutionary change. Here, thinking is defined as being that which underlies creativity, whereby creativity is ‘the development of original ideas that are useful or influential’ (Paulus & Nijstad in Runco 2004: 658). Many texts explain creativity by reference to ‘models of thinking’ which frequently describe the creative process in fixed stages. Creative Problem-solving by Wallis (1926) and many of his successors, for instance, make reference to identifiable stages which include elements such as:

1. Preparation – where preparatory work focuses an individual’s mind on a problem and explores its dimensions.

2. Incubation – where the problem is internalised by the subconscious mind and nothing appears externally to be happening.

3. Intimation – the individual gets a ‘feeling’ that a solution is percolating.

4. Illumination or insight – a creative solution or idea appears from the subconscious state into conscious awareness.

5. Verification – there is conscious verification and evaluation of the solution, followed by application.

These models helpfully acknowledge that both consciously explicit and subconsciously tacit stages are complementary rather than oppositional in the creative process. This seems resonant with how, paradoxically, both co-exist for the drawing practitioner who at various points depends on losing logic whilst at the same time remaining intentional in terms of engagement with the work. I believe that Newman is referring to this paradox when she describes drawing as, ‘the mental and physical act of projection out from the body...is quite a precise act – the most thoughtful and deliberate of acts which...liarbours a necessary thoughtlessness’ (Newman in De Zegher 2003: 81).

However, two aspects of these models appear incongruent to what occurs in practice. Firstly, the orderly and deterministic labels avoid any detailed reference to the confusion and non-linear aspects of the creative process described by many practitioners (Coulson 1996; Gedenryd 1998; Gray & Malins 2004). Secondly, how appropriate is it to refer to creativity by reference to ‘problem solving’ or ‘problem-finding’ (Getzels & Csikszentmihalyi 1975; Garner 1992)? Whilst these descriptions may be relevant in the design process, it is harder to imagine how a problem can be defined either at the outset or at all for others whose focus is in the making rather than the output. It was as if the problem rather than the artefact had now become the finite event in the process rather than being able to focus on the process as an end in itself.

Drawing as a knowledge-constituting process

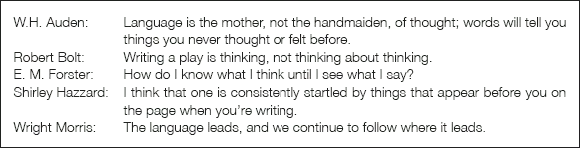

I began to pursue the idea that thinking within the medium might be a way of describing and capturing what was a far more fleeting, complex and intricate process than could be described by reference to a set of deterministic labels. Similarities in the ways in which artists and writers describe their processes are telling in this regard because whilst each often describe how their thinking emerges through the act of making, the mechanics of this often remain hidden from them. David Galbraith identifies this dichotomy in the writer’s creative process by discussing writing as a knowledge-constituting process (Fig. 4) (Galbraith 1992, 1996 & 1999):

Fig. 4: Descriptions of writing as discovery by expert writers selected from Murray in Galbraith 1999: 138.

Galbraith’s explanation that the ‘hidden decision-making lying behind what seems like a spontaneous process’ (Galbraith 1999: 139) occurs as a dialectic or conversation between the writer and what he produces is interesting. The emergence of new ideas in writing occurs, he suggests, through the writer alternately not knowing what he is doing whilst producing an initial text (an implicit act), but knowing what he is doing in responding to it (an explicit act).

Descriptions given by writers and artists resemble each other. E. M. Forster’s comment, ‘how do I know what I think until I see what I say?’ was echoed by artist Richard Talbot in interview when he told me that ‘the image that finally arrives on the paper, comes about through me making decisions in the paper.’ When I spoke to Galbraith himself he proposed that this dialectic or conversational ‘to-ing and fro-ing’ between the drawing practitioner’s internal and external processes might involve ambiguity in the initial tacit act of externalising a drawing, whilst other more explicit processes could resolve ambiguity.

This explanation seems to have resonance with the way in which the practitioner experiences his or her role in keeping a drawing ‘alive’:

Once the pen hits the paper that mark will be there, and there is something challenging about having to be so specific, and trying not to be too specific, because if you are too specific it is not interesting. I don’t want to make something that I know I’m making, I want to make something that I don’t know that I’m making.

(Ansuja Bl...