eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Robert Frank's 'The Americans'

The Art of Documentary Photography

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

In the mid-1950s, Swiss-born New Yorker Robert Frank embarked on a ten-thousand-mile road trip across America, capturing thousands of photographs of all levels of a rapidly changing society. The resultant photo book, The Americans, represents a seminal moment in both photography and in America's understanding of itself. To mark the book's fiftieth anniversary, Jonathan Day revisits this pivotal work and contributes a thoughtful and revealing critical commentary. Though the importance of The Americans has been widely acknowledged, it still retains much of its mystery. This comprehensive analysis places it thoroughly in the context of contemporary photography, literature, music, and advertising from its own period through the present.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Robert Frank's 'The Americans' by Jonathan Day in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

America and The Americans

There are a variety of approaches to history. This may seem a strange way to begin our account, but it is of foundational importance. The outrageous, if possibly short lived, success of our species has developed out of survival imperatives which cause us to observe, analyze, predict and control our environment and the other beings with whom we share our world. We are, then, creatures who look obsessively for patterns. Think of our bizarre but wonderful ability to decode random-looking mathematically generated dots in so-called Magic Eye pictures. We look and look until the Statue of Liberty or some other such is revealed. After the epiphany, after the pattern has been resolved and meaning has been recognized, we are satisfied and never need to look there again. This desire for pattern and meaning is also inescapably present in the assessment and telling of history. There is comfort in a hermetic, tidy account of the past, and comfort too in a measured and recognizable voice, leading us through those long ago and lost intricacies. I am delighted and honoured that you have chosen to vouchsafe me some moments of your time and I hope that my voice will not grate and strain through these few pages, but I also hope that it is not all that you will hear. I have tried whenever possible to let the original and authentic voices speak, the people who were there, living, vital, passionate and involved. I want to try to hear their footsteps and see their expressions as when, for example, Louis Faurer walked for the first time into the studios of Harper’s Junior Bazaar at Madison and 56th and met Robert Frank. I want to smell the city air on the evening sidewalk as Frank asked Kerouac to write his introduction.

I am not claiming to be absent in this account—it is unavoidably me linking these moments together and navigating a course—but I want the picture I paint of this past to be collaged out of the scraps we have left, the moments and memories of the people I quote and thus invoke. It is my hope that the materials I present will validate the account and that these original voices will be the sound in your ears as you read, the sound of history, garbled and crackling like an old valve radio, the sound of the people who made us, the sound of the past.

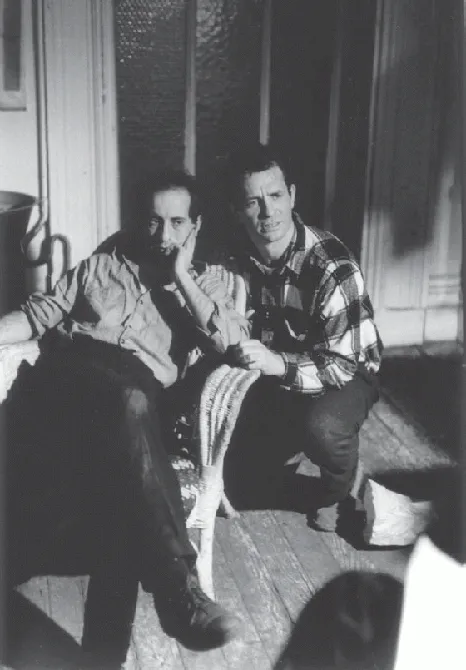

Robert Frank and Jack Kerouac almost exactly a year before the Americans was released in the US. Greenwich Village, New York, 1959. (Photo by John Cohen/Getty Images)

1

FRANK AND THE ’50S

What a poem this is, what poems can be written about this book of pictures some day by some young new writer high by candlelight bending over them describing every gray mysterious detail, the gray film that caught the actual pink juice of human kind… (Kerouac in Frank 1959: 3)

These souvenirs of the past…are partly hidden and curiously resonant, bringing messages which may or may not be welcome, may or may not be real. Disturbing ideas which have a tale to tell or just lie mutely, often justifying the interest one might take in them. (Frank 1991: before plate 1)

…lying in wait, pursuing, sometimes catching the essence of the black and white, the knowledge of where God is. (Frank 1991: after plate 63)

Can you imagine it? Afternoon turning to evening in a canyon-like New York street, long shadows falling across a young man sitting in the driver’s seat of a Ford Business Coupe. The back seat is strewn with his gear and his children, and a Leica shares the front seat with his wife. The enormous expanse of wild America is out there, opened up by highways and interstates, a largely unknown, obscure and guessed-at land, waiting for his wheels and shutter. All around him writers scrawl, making novels in three weeks, saxophonists and trumpeters wail, and poets howl. All of them are desperate to capture this new, never-before-experienced moment, change so palpably in the air, before the arguments are settled and the moment lost. We are sitting here now, 50ish years later, holding in our hands the souvenir he left us of his journey. Long considered and prepared with immense care, it is a mostly wordless, wonderfully eloquent book, describing the world he encountered, his images shaped and selected according to the dictates of his understanding and imagination. It’s a world lost to us now, but near enough in memory to tug at the strings of our recollections and to massage the intuitions of our own histories. I was born in the year The Americans was published: its story is also my story.

How do we describe Robert Frank? How can the conditions that climaxed in The Americans be understood? What in his makeup, his history and experience led him to drive out across that enormous country, exactly as Jack Kerouac was rendering everything associated with the American road iconic for a generation?

Robert Frank was born in 1924 in Switzerland and grew up as a wealthy Jewish child in Zurich. His father was a businessman and Frank was expected to follow in his footsteps:

I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to be but I knew what I didn’t want. Switzerland was a very traditional place where you were expected to do what your father did—follow some sort of directions that were laid down. I didn’t want the restrictions of life that my parents had, their concerns about money and respectability and all. I took up photography as a first little step to get out of the orbit that they prescribed for me. (Frank in Johnson 1989: 28)

He chose to decline his expected role in his father’s business, and studied photography instead. He worked hard and was acknowledged and liked in the Swiss photographic community.

The turmoil and tragedy of the Second World War had an unavoidable influence on Frank:

The war was interesting—the fear that I saw in my parents. If Hitler invaded Switzerland—and there was very little to stop him—that would have been the end of them. It was an unforgettable situation. I watched the grown ups decide what to do—when to change your name, whatever. It’s on the radio everyday. You hear that guy [Hitler] talking—threatening—cursing the Jews. It’s forever in your mind—like a smell, the voice of that man—of Goering, of Goebbels—these were evil characters. Of course you’re impressed… Being Jewish and living with the threat of Hitler must have been a very big part of my understanding… (Frank in Johnson 1989: 26–27)

Instead of settling into his Swiss Jewish photographic world, he again defeated expectations and moved to Paris, and then New York:

The war was over and I wanted to get out of Switzerland. I didn’t want to build my future there. The country was too closed, too small for me. When I got to America I saw right away that everything was open, that you could do anything. And how you were accepted depended on what you did with it. You could work to satisfy what was in you. Once I came to America I knew I wouldn’t go back. (Frank in Johnson 1989: 28–29)

He was a runaway, a young adventurous photographer driven, along with so many others, by the squall of disbelief and revulsion generated by the destruction and genocide of the Second World War, to the unknown and exciting shores of America. A middle-class European kid who was confronted suddenly by all that the Jazz Age and the nascent Beatnik culture had to offer. New York, when he arrived, had a culture peopled by émigré artists like Piet Mondrian, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko, who had moved there as a result of the war. They lived alongside exciting homegrown talents like Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman. Wonderfully, though, it wasn’t just painting that was happening. Here was the opportunity to listen to Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and the thousand other Bop players in cellars and clubs. Woody Guthrie, the darling of well-heeled, middle-class American radicals desperate for some working-class authenticity, was telling everyone, ‘This land is your land.’ Hipster writers like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg were experimenting and subverting literary expectations, experiments so radical that a ban of Ginsberg’s book Howl (1956) was attempted, only to be defeated by the San Francisco bookstore that published it. The rigid social demarcations of Europe were blurred and muddied in this New World.

Something certainly needed to change. How long could humanity continue its cycles of uneasy peace and all-out war? How many had to die before someone solved the Old World riddle? Where were the saviours? Twice in 30 years Europe had hovered at the brink of annihilation. After the First World War, the Dadaist, Surrealist and Neue Sacklichkeit artists had sung, painted and performed their objections. The League of Nations was formed so that such a catastrophe could never happen again. There’s an irony. The writer Albert Camus and others saw the Absurd as the only description and explanation for the insoluble agony and contradictions of human existence. Sisyphus, who in legend repeatedly pushed his rock to the top of the mountain only to see it plunge down again as a punishment for denying the Gods, was crowned Camus’ hero (Camus 1942). Since life is absurd and there is no recourse to the hope or relief of any other world, Camus argued, this doomed man, accepting his lot and smiling defiance into the teeth of fate, was the ideal model for us all. This ‘taking it on the chin’ stance is important. The period during which Frank conceived and executed his project was the time of the ‘Birth of the Cool’ in jazz music. Leroi Jones described this stance:

The term cool in its original context meant a specific reaction to the world, a specific relationship to one’s environment. To be cool was, in its most accessible meaning, to be calm, even unimpressed, by what horror the world might daily propose. (Jones 1963, in Wall 2009)

Trumpeter Miles Davis was the midwife at the Birth of the Cool. He knew the writer and philosopher John Paul Sartre, a contemporary of Camus, thanks to his Parisienne girlfriend and muse, Juliet Greco. Miles famously said ‘for me, music and life are all about style’ (Wall 2009).

Camus’ ideas filled the playhouses in works by Ionesco, Genet and others. These trickled out into cinema, as Rebel Without a Cause (Ray 1955) and The Wild One (Benedek 1954) heralded emergent youth culture and elevated the energy of working people. Films like A Streetcar Named Desire (Kazan 1951) revealed ghetto romances to be as profound as those imaged in any Old World ‘high’ culture, just as The Grapes of Wrath (Ford 1940) had revealed the true heroism of the world in the form of a broken-hearted mother saving a dying man with the literal milk of human kindness.

European culture was redundant. All its finery and refinement had only led to the palace and the workhouse, to the battlefield and to death. Wilfred Owen spoke for so many young Europeans when he wrote in 1918: ‘I would have poured my spirit without stint. But not through wounds; not on the cess of war.’ (Owen 1994: 60) The only thing the proud and potent movers and shakers of the Old World truly owned was shame.

Something new was badly needed, and clearly it was likely to come from somewhere other than Europe. If Old World leaders were revealed as compromised, acquisitive and self-seeking, then the people destined to save the world would come from somewhere other than the ruling class. In the 1958 US Camera annual, edited by Tom Maloney, Walker Evans wrote an introduction to a series of Frank’s Guggenheim-funded photographs. He underlined this search, quoting George Santayana:

In the classical and romantic tradition of Europe, love, of which there was very little, was supposed to be kindled by beauty, of which there was a great deal; perhaps moral chemistry may be able to reverse this operation, and in the future and in America it may breed beauty out of love. (Maloney 1958: 90)

America had a tradition of levelling classes. It was not a commonwealth by any means, but notions of birth were, and are, less significant than wealth. This social and philosophical position led, as much as anything, to the ‘American System of Manufactures’ (Mayr and Post 1981). This was the revolution in industrial production that so signally undermined European practices of class-appropriate consumption and, surreptitiously, therefore the class system. The method, pioneered in Smith’s Armoury in Connecticut, and then in factories run by Singer, Colt and Ford, insisted on the interchangeability of parts. This standardization allowed items to be repaired easily. The mechanization needed to achieve interchangeability led to the production line, the division of labour and ultimately to mass production. Every item from a production line was designed to be near identical. This didn’t result in higher quality or more intrinsic beauty in objects per se, but it meant that functional objects could be produced much more cheaply and in greater quantities. Crucially, it meant that identical products were available to everyone, regardless of status. In Frank’s time, the ‘American System’ had already contributed significantly to the winning of the second World War by the Allies, and mass-produced ‘consumer goods’ would radically reshape the world. This revolution was coming out of America.

In response to European decadence and failure, artists as well as writers looked to the common man and woman, and the rhythms of everyday ordinariness, for salvation. Gone and going were the love of the artist hero, standing high on some metaphorical cliff, at whose work and life the rest of us could only look with wonder, as she or he lived life with an intensity unavailable to the common person (see the celebrated Casper David Friedrich painting Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1818, Kunsthalle, Hamburg). The tawdry and commonplace was the new place to be. Thus the passion of the music of the fields and factories (Guthrie) was played alongside the strange and wonderful syntheses of the ghettos, where Black, Jewish and Irish modalities spewed out ‘jazz’. This twisting and mercurial music never stood still long enough to be properly grasped, understood or categorized. The rhythms and vocabulary of the ‘hip’ street speech of poor people were incarnated in the works of the ‘Beat poets’ (Cuirara 2002). All of this life, dismissed so often as ‘low’ or vernacular culture, seemed for the first time to hold within it, secreted away and kept from the view of the intelligentsia and elite, the secret ciphers of salvation. The ‘art’ of the everyday—hand-painted billboards, street furniture and vernacular architecture—were the subjects of serious photography (Walker Evans and the Farm Security Administration are examples), which was no longer reserved for reactions to the sublime vastness of Yosemite (Ansell Adams) or the isolated sensuality of natural forms (Edward Weston). Not surprisingly, workers became the new heroes. Dorothea Lange made her Migrant Mother photograph as potent as any previous depiction of the Madonna and Child, picturing the suffering woman who must bear all pain for the sake of her children and yet survive (1936, F S A archive, Library of Congress). Another of her photographs, depicting a woman standing in ploughed fields, testifies silently to the challenges of existence with which she is still so palpably grappling. Her White Angel (1934, National Gallery of Canada) speaks eloquently of white-knuckle survival in the face of adversity, which was all too familiar still in the 1950s. Don’t confuse these works, though, with Socialist works made in Russia and China. There the workers pictured were generic ‘everymen’, stripped of specificity and individuality. These American heroes were real individuals, with complex characters and histories on display.

The picturing of this world was not always positive or sympathetic. These were not all eulogies. Many observers questioned and tested these ideas. Walker Evans exhibits a notable emotional distance in much of his work. He presents his working men, women and children for scrutiny, without the embodied empathy of Lange’s photographs. In his search for beauty and meaning, he imaged bare-board ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword: Robert Frank

- Introduction

- Part One: America and The Americans

- Part Two: Themes In The Americans

- Part Three: The Americans As a Photographic Sequence

- Conclusion

- References

- Photographs in The Americans

- Index