![]()

POLAND

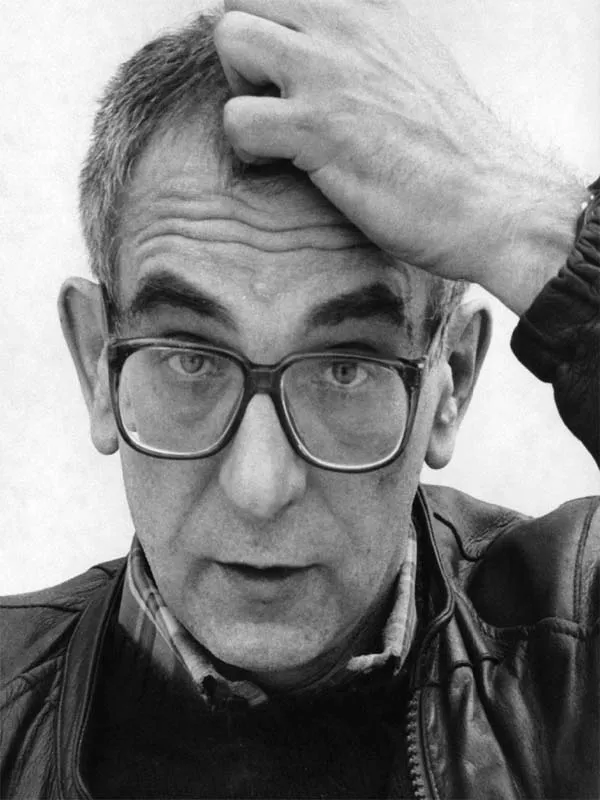

Krzysztof Kieslowski. Photographed by Rommeld Pieukowski.

DIRECTORS

Andrzej Munk

By the time of his premature death in a car crash in 1961 (aged just 39), Andrzej Munk had become one of the pre-eminent directors of the Polish New School - the first wave of young directors that emerged between 1954-58 who took full advantage of the relaxation of political/ideological/artistic pressures that followed in the wake of Stalin's death in 1953, and who rebuilt Polish cinema from the ashes of Socialist realism. Like Andrzej Wajda, Munk began his career making short documentaries whilst studying at the renowned Łódź Film School, although unlike his esteemed colleague he followed his graduation in 1950 by continuing to work on discursive rather than fictive material, making several short projects such as Kolejarskie Słowo/The Railwayman's World (1953) and Gwiarzdy Muszą Pionqc/The Stars Must Shine (1954). He made his solo feature debut, Człowiek na Torze/Man on the Tracks (1957) shortly after co-directing a war film in 1955 entitled Błękitny Krzyż/Men of the Blue Cross. But thereafter he completed only four features before his passing, leaving one film - the sober concentration camp drama Pasażerka/Passenger (1963) - to be completed in his stead by a close friend and colleague.

Andrzej Munk was born in Krakow in 1921, the son of an engineer. He moved to Warsaw during the occupation and had to hide his Jewish heritage whilst working for the military organization PPS. A string of jobs followed, including working on cable cars and for a building company in the wake of the liberation, as well as stints studying law and architecture, the latter interrupted due to the then-prevalent illness of tuberculosis. Always politically-minded, Munk joined the Polish Socialist Party in 1946 before enrolling at the state film school in Łódź two years later (which had opened in 1947 following the post-war dissolution of Poland's first film academy in Krakow). By 1957, before he had even completed his first film, Munk had returned to teach at this institution, and in so doing his status as one of its first and pre-eminent graduates was assured; as indeed was his position alongside the Krakow graduates Jerzy Kawalerowicz and Wojciech J. Has as one of the founding fathers of Polish new cinema.

If there are any discernible, overriding themes that connect the ostensibly disparate films contained within Munk's tragically brief filmography, they are twofold in nature. On the one hand is the role of fate, chance and circumstance in shaping individual subjectivity, agency, action and personal identity; and on the other is the gulf between façade and reality, between image, myth and truth. There is also an attendant structural feature that feeds into these preoccupations; namely the use of flashbacks specifically built around characters recalling their lives and experiences to others (a device that accounts for all but one of Munk's major works). The fact that three of the director's five features were written by the same screenwriter, Jerzy Stefan Stawiński (who also penned Andrzej Wajda's Kanał/Canal [1957]), accounts in part for their cogency and coherence of vision, their quasi-philosophical inquiry and commonalities of tone: dramatic but often comedic; serious in theme but slapstick in execution, and segueing between these two poles in a manner that puts the onus on the viewer to find for themselves exactly what they feel about the material, about where the line between humour and horror lies. Eroica (1958) is especially relevant in this respect, as its initially comedic account of unwitting heroism gradually darkens to the point of closing on a genuinely pointed and poignant moment, something that does not feel unearned, inorganic or forced onto the material precisely because the incredibly precise and detailed screenplay carefully elucidates the tension between the often small-scale actions of the protagonist and the wider stage of history and social crisis and transformation through which he moves (often against the tide). Dina Iordanova has talked about both Eroica and Zezowate szczėście/ Bad Luck (1960) as paradigmatic ‘burden of history’ films (Iordanova 2003: 62-4) wherein the characters predilections, lives and fates run counter to historical change and momentum. As she points out, ‘taking sides in harsh historical moments is [...] compared to the act of gambling’ (Iordanova 2003: 62), and one may extend the metaphor to the notion of fate and chance that animates Munk's circumscribed narratives. In particular, it is a fateful encounter that initiates the recollections of the Holocaust around which Passenger is constructed, whilst chance happenings account for much of what befalls the protagonist of Bad Luck.

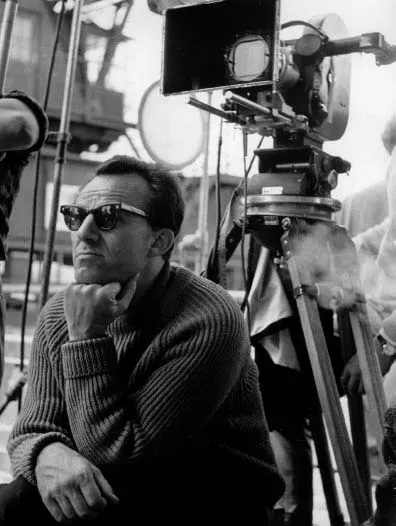

Andrzej Munk.

This construction of an active audience involved in questioning and interacting with the films anticipates in embryonic form the new directions in Yugoslav cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s (Dušan Makavejev in particular). Indeed, where Makavejev uses a collage methodology to juxtapose disparate genres, mediums and narrative forms, so Munk's handling of tonal shifts and transitions implicitly asks the viewer to make their own mind up as to the point of the comedy, specifically about how it relates to what are otherwise dramatic narratives comprised of serious incidents and which are frequently depicted as such (that is, they are not presented as inherently comedic). Given that the war and immediate post-war era factors into this dynamic, the darkly comedic and ironic vision of personal crisis and imperilment at work in Munk's cinema is frequently coupled with a real sense of historical import. And in this regard one can point to him as a director who, like Jerzy Kawalerowicz, conflates both the first and second waves of new Polish cinema: the obsessive, cathartic need to detail specifically national stories, myths and themes that characterises Andrzej Wajda, Wanda Jakubowska and Aleksander Ford one the hand, and the subsequent stories of individual psychology, contemporary alienation and broadly modernist, existentialist concerns by the likes of Roman Polański, Jerzy Skolimowski and Andrzej żuławski on the other.

The fact that Munk had originally studied architecture before turning to the cinema can be keenly felt throughout his work. In all his features he demonstrates a frequently unerring sense of both dramatic space (on and off-screen) and composition that serves to precisely map out and delineate his characters’ physical and psychological states of being. Attendant on this is a predilection for the long-take and often deep-focus cinematography, which, whilst less prominent than in the work of, say, Miklós Jancsó or Belá Tarr (largely because Munk's camera mobility is far more functional, its movement generally dictated by re-framings necessitated by the actors’ blocking), is nonetheless the product of a keenly intelligent cinematic mind. The long-takes are used primarily to de-suture the viewer, to keep them at one remove from the characters in support of objective narratives in which the audience generally arrives at a picture as a whole that is largely denied to any specific protagonist. Again, Eroica crystallizes this facet of Munk's work, with its second story (its narrative is comprised of two distinct tales) developing around a picture of POW camp internment in which many of the soldiers hold dear a story about a colleague who they erroneously believe to have escaped, one that runs explicitly counter to the facts. The later comedy Bad Luck is also pertinent here, as it becomes increasingly clear that the protagonist's view of himself as perennially ill-served by fate is wide of the mark, and that his own ill-luck is something that has, at least in part, been engendered by nothing and no-one so much as himself.

This point can be seen to most dramatic effect in Man on the Tracks, a film often cited alongside the likes of Kurosawa's Rashōmon/Rashomon (1950) due to its a-linear structure predicated on different accounts of a single subject; in this case, a man who has died following an accident on a rail line. This is an erroneous comparison, however, as Munk's film does not provide contrasting perspectives on one event. Instead, a composite picture is painted of the man's personality and professional nature, with the director and writer (who are not really concerned with the nature of relative truth) ultimately allowing the audience to see the man in a more complete and indeed empathetic way than any of the individuals who offer their thoughts and memories of him, and who have been personally swayed by unpleasant encounters.

Although Munk was held in the highest regard by his New School contemporaries (especially Wajda and Roman Polański), he has remained curiously marginal within much discourse on Polish cinema. Despite being recognized for his ‘exceptional talent’ (Liehm & Liehm 1980: 788) in an essay on post-war Polish film-making in the landmark diptych of books Cinema: A Critical Dictionary, he nonetheless warrants only three short paragraphs that amount to little more than a summary of his films, with all save Eroica given no critical elucidation or reading whatever. Similarly, the profile in the otherwise commendable BFI Companion to Eastern European and Russian Cinema (2000) does not even mention certain of Munk's pictures. Instead, in what is no more summation of his career rather than an attempt to distil his style or methodology, the salient facts of his life and work are outlined with such brevity that one would be forgiven for thinking that Munk lacked those tenets deemed central to authorial canonization; namely, the thematic pre-occupations and intrinsic stylistic norms already identified. At a time when both Polish cinema and discourse thereof has returned to a certain degree of international visibility (2010 saw the publication of two new books on the subject, whilst the annual British touring film programme of new works from the always popular and prevalent Polish Film Festival continues apace), and when all four of the director's major works are available on DVD, the time to properly assess the rich oeuvre of Andrzej Munk is long overdue.

Adam Bingham

References

Iordanova, Dina (2003), Cinema of the Other Europe: The Industry and Artistry of East Central European Film, Great Britain: Wallflower Press.

Liehm, Antonin J. and Liehm, Mira (1980), ‘Polish Cinema since the War’, in Richard Roud (ed.), Cinema: A Critical Dictionary, Great Britain: Martin Secker & Warburg.

Andrzej Wajda

Andrzej Wajda is not only ‘the most prominent representative of the Polish school’ (Urgošiková 2001: np) who achieved ‘god-like status in his native Poland’ (Crawshaw 2000), but he also remains ‘one of the great figures in European cinema during the second half of the twentieth-century [whose] long career reminds us, in a post-Cold War situation, of that tangled relationship between cinema and politics as we now sense in countries as diverse as Iran and China’ (Orr & Ostrowska 2003: 28). Best known for his ‘war trilogy’ - Pokolenie/A Generation (1955), Kanał/Canal (1957) and Popiół i diament/ Ashes and Diamonds (1958), as well as the anti-Stalinist Człowiekz marmuru/Man of Marble (1977) and its sequel, the pro-Solidarity Człowiek z żelaza/Man of Iron (1981)-Wajda's 1989 election as a senator in the Polish Solidarity movement exemplifies the extent of how tangled the relationship often is between cinema and politics. In Wajda's own words:

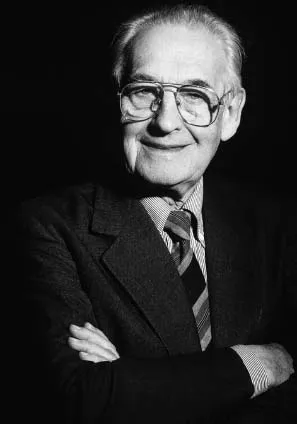

Andrzej Wajda. Photographed By Stephane Fefer.

[...] soon after World War I, the demons of Fascism emerged, quickly followed by Stalinism, which did promise a better future though real life soon shattered such hopes. I am proud that Polish cinema addressed these two matters. It spoke out against the Nazi war and made films that challenged the lie of Stalinism [...] it was very important that our voice was heard on the other side of the Iron Curtain too. We felt then that Polish cinema had a duty not only to speak about itself but also to communicate with those on the other side in the Cold War [...] our war films showed the truth about the Polish ‘October’ in 1956 to those on the other side of the Iron Curtain, and later our films in August 1980 let the world know that something fundamental was happening in Poland. (Wajda 2003: 11-12)

Even Wajda's treatment of the French Revolution in his Dan...