![]()

HISTORICAL

American films depicting historical events can be traced back as far as the nineteenth century. The Edison Company produced a number of ‘historical tableaux’ for its Kinetoscope, among them The Execution of Mary Queen of Scots (1895), essentially a ‘trick shot’ dramatization of the beheading using a concealed edit to substitute the actor for a dummy. Edison bought this spectacle up to date in 1901 with a film depicting the electrocution of Leon Czolgosz, the assassin of President McKinley. Produced less than two weeks after Czolgosz’s actual execution and employing realistic mise-en-scène, the film might be said to muddy the distinction between representation and reality in a way that prefigures the subsequent development of the historical film in America. The most hotly-debated example of this tendency in recent years concerns the assassination of another American President. Released in 1992, Oliver Stone’s JFK was widely criticized for integrating documentary footage with detailed reconstructions of historical events in order to illustrate theories about the Kennedy assassination. In a debate that traversed both mainstream media and academic discourse, Stone was accused of ‘contempt for history’ (Hoff 1996: 1173) and of misleading ‘vulnerable audiences herded in darkened halls’ (Ambrose et al 2000: 216). For its defenders, on the other hand, JFK successfully challenged the principle of objectivity and the straightforward distinction between ‘truth’ and ‘myth’ which much mainstream history writing takes for granted. As Robert Rosenstone put it, the film ‘questions history as a mode of knowledge … and yet asserts our need for it’ (Rosenstone 2006: 129).

As JFK’s fraught reception indicates, Hollywood history films have frequently faced criticism for incorporating and omitting elements which depart from the historical record. It is worth noting, however, that any film which dramatizes or restages the past from the perspective of the present necessarily strikes a balance between fact and fiction, no matter how closely it hews to documentary evidence. As Pierre Sorlin argues, historical films ‘have to reconstruct in a purely imaginary way the greater part of what they show’ (Sorlin 1980: 21). Moreover, as theorists such as Hayden White have argued, any attempt to translate information about the past into a historical narrative inevitably involves rhetorical conventions that lead to a form of fiction. Although many would argue that the inventions of Hollywood historical films and the shortcomings of academic history are not equivalent, it should be clear that no account of the past can claim absolute objectivity. David Eldridge has recently defined historical cinema as ‘all films which utilise ideas about the past contain and reflect ideas about “history”’ (Eldridge 2006: 5). This definition throws open the doors to a huge range of films, including well-established genres such as the Western and the war film, which are examined elsewhere in this volume. But, as with many other Hollywood genres, the history film is not a unified set of textual practices and it frequently overlaps with other generic categories. Nevertheless, Eldridge’s definition allows historical films to be approached not simply in terms of their fidelity or otherwise to historical data but, rather, as part of a longstanding desire of film-makers and their audiences to engage with representations of the past.

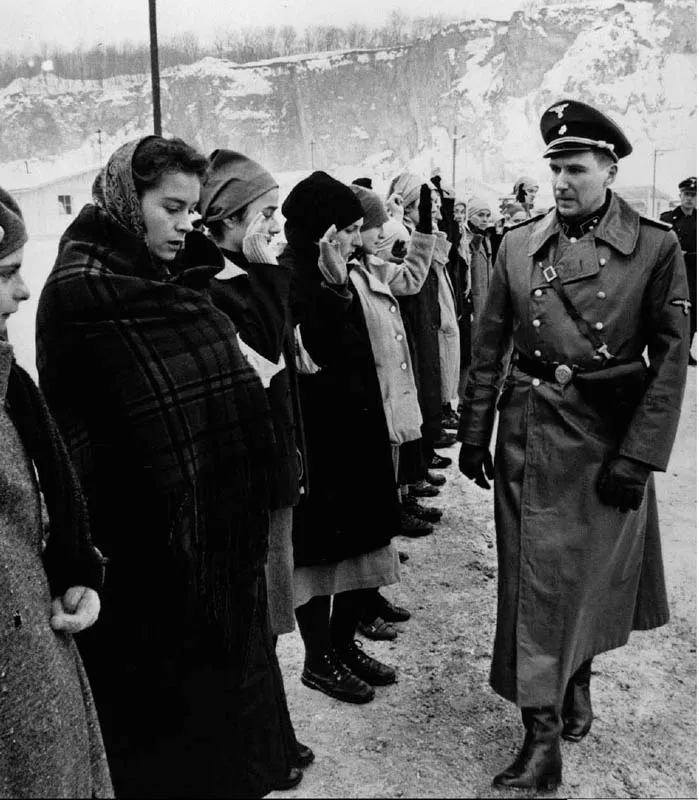

Indeed, history has been central to some of the highest profile Hollywood films of the past century. In 1915, DW Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation demonstrated that lavish depictions of American history, no matter how dubious, had enormous box office potential. Griffith proposed that historical films would soon supersede books as tools for learning about the past, but this didactic spirit was not shared by other major film-makers of the period. The highest profile history films of the early sound era focused on history beyond America’s borders. At Paramount, Cecil B DeMille used the ancient world as a means to put sex and spectacle on the screen in The Sign of the Cross (1932) and Cleopatra (1934). For Warner Bros, conversely, the more recent history of Europe provided a way to add prestige to their production roster. In particular, the Paul Muni bio-pics The Story of Louis Pasteur (1936) and The Life of Emile Zola (1937) narrate the past as great men struggling against the odds for noble causes. American history was not completely forgotten, however. Gangster films such as The Public Enemy (1931) and Scarface (1932) examined America’s recent urban past, while Westerns like Cimarron (1931) and Union Pacific (1939) narrated and often mythologized the westward expansion of America’s frontier. As hostilities gathered pace in Europe, some Hollywood film-makers used the past as a way to caution viewers about the present. Films such as Juarez (1939) and That Hamilton Woman (1941) can be read as allegories of the growing Nazi threat.

In the 1950s, as the Hollywood studios adjusted to fragmentation of the cinema marketplace, historical cinema became absolutely central to their operations. In particular, lavish, spectacular, ancient world epics such as Quo Vadis (1951) and The Ten Commandments (1956) allowed Hollywood to develop new distribution strategies and new technologies of exhibition (notably widescreen) that would allow cinema to compete for dwindling audiences. The fashion for spectacular epics ended with a series of high-profile failures in the late 1960s, but many of the films that displaced them also drew on history. Among the major films of the New Hollywood movement, Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Serpico (1973), All the President’s Men (1976) and Raging Bull (1980) combine stories from America’s past with a fresh presentational style. War films, notably Apocalypse Now (1979), Platoon (1986) and Saving Private Ryan (1998) also allowed Hollywood film-makers to reflect changing attitudes to America’s various military engagements following the Vietnam War. In the final years of the twentieth century, films such as Braveheart (1995), Titanic (1997), Gladiator (2000) refreshed conventions from the historical epics of the 1950s for new audiences with CGI and more realistic bloodshed. Historical films continued to be controversial, most conspicuously the work of Ol...