![]()

GIRLISH GAMES: PLAYFULNESS AND ‘DRAWINGNESS’ IN THE WORK OF FRANCESCA WOODMAN AND LUCY GUNNING

Harriet Riches

In the still-influential essay written to accompany the first posthumous exhibition of the work of the American photographer Francesca Woodman in 1986, Abigail Solomon-Godeau interpreted her project through the lens of the critical concerns of the period.1 Quoting the words of Bob Dylan, Solomon-Godeau suggested that the young artist’s repetitive and seemingly obsessive photographic representation of the female body worked collectively to expose the cultural constructions of femininity and articulate what it is to be ‘just like a woman’.2 Although curtailed by her suicide at the age of just 22 in 1981, Woodman’s brief career produced a focused body of imagery, one that according to Solomon-Godeau cannot be moulded to fit the conventional model of progressive development from youthful juvenilia to artistic maturity. With its sustained focus on the naked female body as its subject, often posed with the props and paraphernalia associated with the tropes through which a narcissistic or sexualized feminine identity has been traditionally represented, Woodman’s photography is interpreted by Solomon-Godeau as an exploratory inventory of the woman’s body as an icon of desire. Covering her bared skin with fur and sensuous fabrics, or peering into the surfaces of her many mirrors, Woodman’s acts of apparent self-representation presented a well-focused project whose parameters were clearly defined ‘by her late teens’.3

But by investing in Woodman’s photography of her own youthful form a quite sophisticated and politicized concern for the medium’s fetishizing focus and easy propensity for the objectification of femininity, such accounts obscure the playful aspects of the artist’s process and ignore many instances of a far more childlike self-representation. In fact, that this body of work is the product of a young artist barely out of late adolescence has posed a problem for its subsequent interpretation. For some, it is a cause for celebration: Solomon-Godeau, for example, describes Woodman as that rarest of beings, a female photographic ‘prodigy’.4 While intended to counter the masculinity more usually associated with such a description, this categorization has also resulted in the positioning of Woodman’s work within a kind of contextual vacuum in which all connections to its historical, artistic and photographic precedents have been all but severed.5 For others, Woodman’s photographs are read as the diaristic traces of an unstable adolescent subject, symptomatic of the way that the facts of her youth and early suicide have contributed to an ultimately unproductive immortalization that ensured her admittance into what Lorraine Kenny describes as the ‘canon of troubled women artists’ just a few years after her death.6

Undoubtedly a precocious talent, Woodman produced some 700 or so photographs from the earliest self-portraits she began in very early adolescence at just 12 years of age, through the substantial body of work produced as a student at Rhode Island School of Design, to the commercially oriented fashion imagery and the unfinished series and unrealized projects she started as she took her first tentative steps as a newly graduated photographer working in New York’s art world at the turn of the 1980s. Influenced as much by contemporary photographic practices from the worlds of fashion and fine art as by the surrealism that haunts her work, Woodman’s photographic subject was more often than not her own young, naked and undeniably beautiful body, or that of a friend or colleague chosen for more than a passing resemblance to herself. Usually hiding behind swirls of fabric or papery masks, blurring her features to the point of indistinction, or posing so as to be cut-off by the limits of the print’s rectilinear frame, the artist rarely showed her face. Naked, decontextualized and unindividualized, the construction of her own image as that of the female nude lends itself to being interpreted as representative of the masquerade of femininity—of being ‘like’ a woman—as she repeatedly became the photograph’s fetishized object.

However, within that body of work, there are almost as many instances in which the stability of that apparently early and clearly defined focus might be questioned. In many photographs Woodman appears fully clothed, her use of costume as integral as her use of the props that were an important element of her essentially performative project, one that has often been overlooked. Collecting clothing from thrift stores and vintage shops in New York and London, and hoarding gifts and precious hand-me-downs from her grandmother, Woodman created an art-school persona in life that often overspilled the frame of her photographs, acting out an identity that is seemingly both anachronistic and other-worldly, and at the same time emphatically redolent of the period in which she lived.7

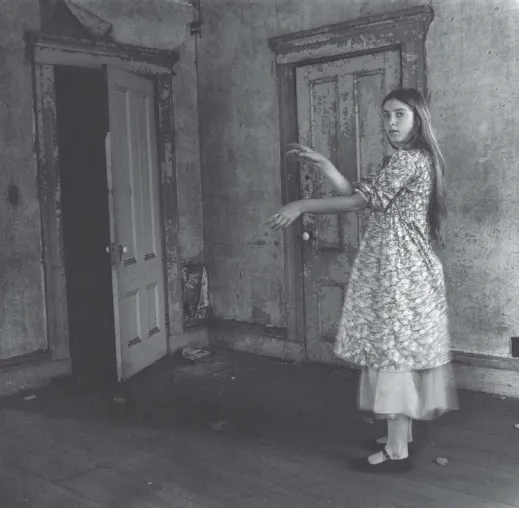

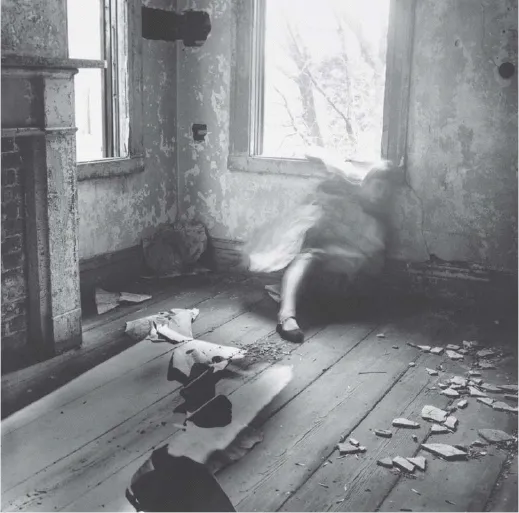

But here and there Woodman appears quite differently. One early untitled shot (Figure 1) shows the artist fully clothed, in a youthful and decorative patterned dress, with her hair loose. Peering up from beneath the glass surface of a coffee table, she is confined by its frame and the mirror-like surface of the glass pane. In some of what have become Woodman’s most-often reproduced images, she appears in a similar guise within the decaying spaces of an old abandoned house she found in the local environs surrounding her art school in Providence. In another from 1975/1976 (Figure 2), we see a rare glimpse of her face as she engages the camera with a steady gaze. A slight swish of the fabric of her flowery dress has been captured as a soft blur, suggestive of a motion echoed by the door in the background that appears to be opening as Woodman draws it towards her with a just-stilled hand gesture. The blurred effect is heightened in another work from the same loosely collected series that has been given the title House #3 (1976) (Figure 3). Here, she appears as a shifting form crouching under the searing white space of a bright, over-exposed window; and in a third shot taken in the same space, House #4 (1976) (Figure 4), Woodman has crawled behind the upended mantel of the fireplace tilted to rest against the chimney breast. With her legs astride its upright supporting columns, Woodman appears to be in the process of being engulfed by its form as if disappearing into the architecture of the hearth.

Figure 1: Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Providence, RI (RISD), 1975/1979.

Courtesy George and Betty Woodman.

Figure 2: Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975/1976.

Courtesy George and Betty Woodman.

Figure 3: Francesca Woodman, House #3, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976.

Courtesy George and Betty Woodman.

Figure 4: Francesca Woodman, House #4, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976.

Courtesy George and Betty Woodman.

Dressed up throughout, Woodman’s appearance, the blur of her bodily movement and the glimpses of her face deny the stasis and abstracted generality of the decontextualized nude she frames elsewhere. Wearing a floral frock that the artist’s mother told Carol Mavor was a much-loved Liberty print dress made for Woodman as a young girl, worn here ‘like a Victorian breakfast coat over a plain longer skirt’, the artist takes on a more childlike appearance.8 With her hair loosened to flow over her shoulders and down her back (in sharp contrast to the more elegant sophistication of the chignon she affects elsewhere), in schoolgirl knee-high socks or bare-legged in what have become her trademark Mary-Jane style Chinese slippers, Woodman constructs an adolescent—or perhaps more accurately, a ‘girlish’ identity—that belies her eighteen years.

Perhaps Woodman had in mind here the performance of an ‘Alice’-like identity, an identity that critics such as Margaret Sundell and David Levi Strauss have recognized in passing, her costumed body being evocative of the character in John Tenniel’s illustrations of Lewis Carroll’s stories.9 Describing Woodman’s relationship to the darkened space behind the half-opened door depicted in Figure 2, Levi Strauss quotes from Carroll’s text, describing the little peep of a dark passage Alice sees through the looking-glass—a passage that is both familiar yet utterly different from what she has known before.10 There is certainly in Woo...