eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Spectacular Death

Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Mortality and (Un)representability

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Spectacular Death

Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Mortality and (Un)representability

About this book

An interdisciplinary collection of essays on the medical and social articulation of death, this anthology considers to what extent a subject as elusive as death can be examined. Though it touches us all, we can perceive it only in life – with the predictable result that we treat it either as a clinical or social problem to be managed or as a phenomenon to be studied quantitatively. This volume goes beyond these models to question self-reflexively how the management of death is organized and motivated and the ways that death is at once feared and embraced. Drawing on the very latest in the medical humanities, Spectacular Death gives us an enlightening new perspective on death from the classical world to the twenty-first century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Spectacular Death by Tristanne Connolly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Collections. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

6

ENJOYMENT’S PETRIFICATION: THE LUXOR OBELISK IN A MELANCHOLIC CENTURY

Michael Follert

When the guillotine was erected at Place de la Révolution in January of 1793, it assumed the post of a bronze statue of Louis XVI’s forebear, felled and melted down only months earlier. As the most central square in Paris, it had formerly celebrated the dominion of the king as Place Louis XV. Renamed and baptized in Louis’s blood, the square would soon become stage for the execution of several thousand suspected counter-revolutionaries. The guillotine periodically carried out its swift and spectacular justice here until the smell of blood compelled local residents to seek its removal to more modest dwellings (Hamer 1992: 82). Four decades later, in 1833, a hulking, granite obelisk of Egyptian antiquity was erected at the center of the same square as if to recall the guillotine’s former dominion. The Luxor Obelisk, a gift of the Viceroy of Egypt, has remained there with remarkable staying power—much longer than did the crumbling plaster Statue de la Liberté of the Revolution or the incomplete expiatory monument to “Louis XVI, martyr” during the Bourbon Restoration (1814–1830). The monuments once inscribing the site with an explicit view to its legacy were leveled in little time and replaced by an “immutable stone” of a civilization long-buried, curiously making no explicit statement on the history it inherited.

The Event and Its Stain

When Arendt (1990: 50) speaks of the public memory of the French Revolution, it is the dates corresponding to the Fall of the Bastille (July 14), the death of Robespierre (9 Thermidor on the French Republican Calendar), and the rise of Napoleon (18 Brumaire) that appear to resound the most. But 2 Pluviôse, the date of Louis XVI’s execution, does not seem to merit significant notice. Echoing George Bataille’s notion that the execution of the king inaugurated the “criminal nature of the French people, its existence in guilt” (Cox 2006 113), Jean-François Lyotard, a thinker less immediately associated with the French Revolution, argues that today the memory of this act haunts all of the politics, the philosophy and the literature of the French. The integrity of any text or decree after the regicide is thence measured up against that singular event, “[le] crime [qui] a été perpétré en France en 1792 […qu’on] a tué un brave roi tout-à-fait aimiable” (Lyotard 1985: 583).1

Indeed, Arendt may be correct in her exclusion, ascertaining that this date has mostly been eclipsed from public memory. Lyotard’s point, however, is that the memory is more subtextual, haunting each system of meaning or rule grounded in its respective longing for legitimacy. Lyotard also tells us that no American, Briton nor German—pace Arendt—could truly understand the tenacity of this crime’s stain, despite their shared inheritance of the democratic tradition. The very obscurity of the memory of the event in Lyotard’s own writing, however, is a point of some irony: he mistakenly identifies the year of the execution as 1792 rather than 1793, perhaps confounding the date of the king’s deposition with the date of the regicide. The memory, despite its insistence in one manner, for Lyotard, reveals itself distorted. What exactly, then, is he tapping into here, and—without fetishizing history qua the memorization of dates—why this slip? How does the singularity of this event, now more than two centuries past, register in French public memory? Indeed, what can this non-descript monument, the Luxor Obelisk (Fig. 6.1), tell us about how the French oriented toward the traumatic moments of the Revolution in the century that followed it, in this “century of commemorations but also of forgetfulness” (Hollier 1994: 812)?

Melancholic Glory

During the period of the July Monarchy (1830–1848), Victor Hugo remarked upon the festival of 1839 celebrating the death of the king: “under the spell of the obelisk, the populace dances, a forgetful Oedipus, on the stage of its crime” (Hollier 1994: 675). For the festival’s participants, save the writer, the violent history of the site appears to be displaced by its new monument. Where once reigned the rites of expiation or explicit celebration in the early days following the regicide emerged a ritual of forgetting. One travel writer commented in the same period on the fate of the site that had come to be named Place de la Concorde: “The voice of the people…as if still more desirous of obliterating the past and living only for the present, gives it the simple designation of Place de l’Obelisque” (Simpson 1847: 430). The obelisk, he suggests, effaced its predecessors, with the square taking the former as its new referent. This archaeo-logic of displacing a more recent history by excavating a more remote past denotes a relationship with “the Orient” that extended far beyond France’s failed conquest of Egypt under Napoleon. In an inversion of the iconoclasm of the pre-Thermidorian days of the Revolution, the French in the nineteenth century “[remembered] in order to forget” (Wengrow 2005: 139).

Fig. 6.1. Gaspard Gobaux, Place Louis XV, 1850. Courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France.

A day following the execution of Louis XVI, the editor of Le Patriote français pleaded, “Illustrious day! Never to be forgotten day! May you come down to posterity without stain! Calumny be ever far from you! Historians, show yourselves worthy of your times! Write the truth, and nothing but the truth. Never was the truth so sacred, never so becoming to tell!” (Arasse 1989: 57). This injunction would surely have resonated with the inaugural historian of the Revolution, Jules Michelet, who inherited the memory of the Revolutionary moment from his father. Writing his Histoire de la Révolution française, published in 1847, Michelet lamented that the people of France had “repudiated its friend… Nay, its own father, the great eighteenth century! They have forgotten,” he added, “that the eighteenth century founded liberty on the enfranchisement of the mind” (qtd. in Huet 1997: 101). While the revolutionaries themselves sought to “do away with every remnant of the past” (Huet 1997: 132–3), Michelet rebuked his contemporaries for doing the same. He wished, rather, to restore to the revolutionary moment the glory it was due, recalling its Enlightenment legacy even at the expense of exhuming its traumatic excesses.

Drawing largely on the work of Michelet, Marie-Hélène Huet’s Mourning Glory2 examines how post-Revolutionary France dealt with the sublime character of the founding moments of the First Republic at the levels of aesthetic and political forms of representation. “Mourning” in Huet’s work implies an attempt at reconciliation with the past, yet an attempt that does not, and indeed cannot, completely put the past to rest. There is a remainder—something that continues to insist upon public memory. To take Freud’s clinical understanding of the term,3 the process of mourning entails the subject completely de-cathecting a lost or dead love-object and consequently becoming open to new objects. Yet something else not quite captured by Huet’s title seems to be at stake with the relation to the past conveyed here. Though deprived of her wordplay, we might do better to consider, using Freud’s complementary term, a melancholic relation to glory.4

Crimen immortale, inexpiabile

The Janus-faced character of the French Revolution has been the object of considerable scrutiny in recent scholarly work. If its ennobling moments, like the storming of the Bastille or the enunciation of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, are what survive most vividly in the hallowed historical imagination of the Revolution, then the September Massacres, the trial and execution of Louis XVI, and the ensuing Reign of Terror persist merely as a muted stain upon revolutionary glory. This tension reached a peak, notes Huet, during the July Monarchy which rededicated the Panthéon to the memory of “the great (dead) men of the Fatherland” while scores of bodies covered in quicklime still languished in the “wasteland of the cemeteries of the Terror” (1997: 5). French public memory seems to have relegated the horrifying moments of the Revolution, despite what I argue to be their simultaneously auspicious character, to its footnotes.5

Jean Baudrillard claims that, today, history has produced “a perfectly pious vision of the Revolution, cast in terms of the Rights of Man… A vision which allows [the French] to eliminate Saint-Just from the Dictionnaire de la Révolution” (1994a: 23–4). Saint-Just’s vanishing act illustrates the status of the Jacobins, the agents of the Terror and campaigners for the king’s execution, as the “vanishing mediator” between the ancien régime and liberal democracy. As Žižek tells us, it is “difficult and disquieting to acknowledge and assume fully the fact that, without the Jacobinical ‘excess,’ there would be no ‘normal’ pluralistic democracy” (2002: 184).6 While this excess or sublime violence was in one sense necessary to the eventual institution of democracy, it remained unassimilable to and persists as a stain on the latter.

The excesses of the Revolution perhaps attained their most traumatic character in the regicide. With the registration of the king’s death within a juridical frame that still relied in the last instance upon a principle of sovereignty that he embodied, the law consumed itself like a snake eating its own tail. The Revolutionary Constitution of 1791 reaffirmed, after all, just two years prior to Louis’s execution, the king’s inviolability as sovereign. As Goldhammer notes, the trying of Louis XVI as “Louis Capet”—as a citizen—was merely a “strategic revolutionary fiction that permitted his judgment in a court that would otherwise have no jurisdiction—no legitimacy—to judge a sacred being” (2005: 19).7 It is because of this “criminal” inversion of the law that Kant, himself a republican sympathizer, lamented “it is as if the state commits suicide” when the people put to death their very guarantor of legitimacy by formal execution (1996: 98).8 Unlike an assassination, the act of putting a sovereign to death by juridical process violated the principle of legitimacy in such a manner that it could, according to Kant, “never be forgiven either in this world or the next” (1996: 97). Such an act destroys the possibility of the collectivity surviving by any legitimate means. Or, to put it otherwise, the collectivity survives but, as Lyotard suggests, under the “signe d’un crime.” This is perhaps partly why the Revolution “left no monuments to commemorate its achievements” (Huet 1997: 4). The only testament to the Revolution remains the Champ de Mars, “a sandy plain,” Michelet observed, one “as flat as Arabia” (Huet 1997: 102). Michelet remarked in 1847 upon the obscurity of the memory of the Revolution in the cityscape of Paris in contrast with the lasting markers of France’s then-fallen regimes: “…the Empire has its column and has furthermore taken the Arc de Triomphe over almost entirely for itself; the monarchy has its Louvre and its Invalides; the feudal Church of 1200 is still enthroned in majesty in Notre-Dame; even the Romans have the thermal baths of Caesar. And the Revolution’s monument is… emptiness” (Hamer 1992: 82).

There was a profundity to the “wastelands” of the Revolution like the Champ de Mars or the cemetery of the Terror, haunted by civic neglect in Michelet’s time. These sites intimated something that could not be captured by “any piece of human architecture” (Huet 1997: 102). Michelet was understandably hostile to the placement of the Luxor Obelisk there, in the center of Paris, on such an auspicious square. This was a site where, he announced, “the Nation alone has the right to be represented” (Hollier 1994: 673). The Revolution, in his view, had a sublime character and the obelisk was out of place in this public square—the place of the people. Describing it as the “obelisk of the pharaohs,” Michelet preferred it hidden away in the Louvre (“the palace of the kings”), along with the relics of the ancien régime. The remains of the monarchic past needed to be placed in their properly sepulchral domain (Higonnet 2005: 62). Indeed, notable contemporaries from across the political spectrum including Hugo, Borel, Chateaubriand and Balzac were also critical of the sheer out-of-place-ness of the obelisk. Yet for all of its obscurity, the obelisk retains a strange fit to the site’s legacy of revolutionary excess.

The Obelisk and its Other

Monuments are carried away on the river of time. Suddenly, on the Place de la Concorde, there is silence. The name changes: Place de la Terreur. Obelisks and pyramids collapse as the metonymic pollutions of nearby rivers (whether Nile or Seine) reach them. (Hollier 1992: 169–70)

The importation of the obelisk to the center of Paris, where once stood the guillotine, appears at first symbolically at odds with the “ever-exilic, ever-transitory place of death in modern urban life” (Vidler 2000: 123). Foucault speaks of the shift in urban development in the early nineteenth century whereby cemeteries, once the “sacred and immortal heart of the city,” were displaced to the outskirts of the latter with a view to managing contagion and public health (1986: 25). Yet it would seem that there persists in city life a fascination with the spectacle of death and its remains. In Vidler’s reading of Bataille, the Luxor Obelisk resembles a forensic chalk-etched “x” marking the scene of a crime. Death here returns to the “sacred and immortal heart of the city” through the obelisk even as it strains to obliterate the memory of the very death it marks. The monument, like a cenotaph, stands in for the place of death so that death will not appear to us as such (Hollier 1992: 36).

If the obelisk works to bury the past, it simultaneously undoes this by subliminally recalling the scene of death. In one respect, we see how the obelisk is read against and through its more majestic counterpart, the pyramid. In Bataille’s reading, the obelisk was to the pharaoh’s sovereignty what the pyramid was to his corpse (1985: 215). Both structures point upward—the former like a beam of sunlight, reified. Yet the obelisk is traditionally capped with a small pyramid, as Mark Taylor notes, undercutting the “monumental desire” that the former represents (1987: 120). The living pharaoh’s sovereignty, we may say, as displayed in this architectural indeterminacy, remained closely hinged upon the interred remains of his dead forebears, just as the dead father in Freud sustains the Law as its ultimate symbolic authority (1953: 140–61).

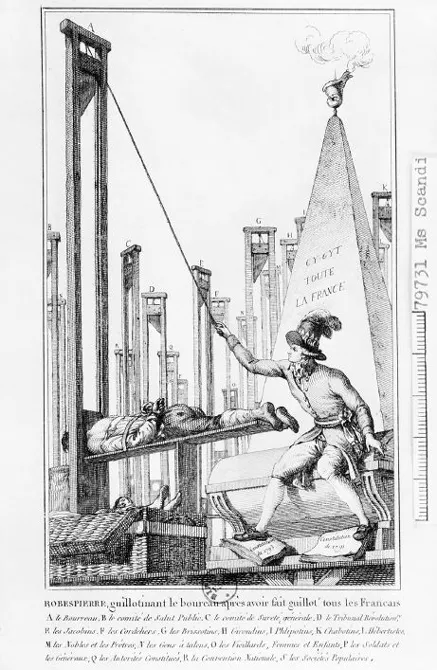

The indistinction between obelisk and pyramid is further betrayed in one notable Revolutionary period image (Fig. 6.2). The engraving shows Robespierre at the height of the Terror, guillotining the state executioner. Robespierre here, literally pulling the strings behind the violence, is primed to decapitate the chief functionary of the executions in an omen to the former’s own demise soon to follow. Behind the primary scene is a field of guillotines, multiply reduplicated as if to account for each of the deaths incurred under the Terror. Near front stands a pyramid-obelisk structure with the inscription: “Cy git toute la France” (“Here lies all of France”), satirizing the extremes to which the Jacobins would go to purify the nascent body politic—that, if necessary, all of the French could be put to death to save “the nation.” The obelisk that would eventually find its way to Place de la Concorde, and that is bizarrely anticipated here four decades in advance. This, however, had little to do with Robespierre himself, who had the guillotine moved to a more remote location, the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, and then one even more remote, Barrière du Thrône, during the years of the Terror (Hollier 1994: 588). The coincidence of the pyramid-obelisk structure and Robespierre is strange also if we consider Robespierre’s disdain for the spectacular quality that executions had previously attained. No doubt he would find such a memorial, publicizing the merely quotidian acts of swift Revolutionary justice, out of place.

Fig. 6.2. Unknown artist, Robespierre Guillotining the Executioner After Having Guillotined All the French, ca. 1794. Courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Looking at the image, one is struck by how the structure behind the scene of the execution appears as a strange hybrid of the pyramid and the obelisk. It bears some of the formal qualities of the obelisk (it has an inscription; it is situated upon a stone base), yet it lacks the typical shaft-like form of the latter. Recent scholarly references to this image also betray the difficulty in properly classifying it. Porterfield describes the object depicted here as a “pyramid-obelisk” structure (1998: 20), while Burton on one page uses the term “pyramid,” and then “obelisk” on the next, to describe the very same image (2001: 54–5)! However, the image, in its indistinction, unwittingly tells us something about sovereignty: that sovereignty achieves its highest expression in the power over the lives of the members of the polity—as the monopoly-holder of legitimate violence. The paradox here is that popular sovereignty might...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Classical Death: Comedy and Tragedy

- Enlightenment and Romanticism: Aestheticizing the Corpse

- Memorialization and the City

- Policy: Border Control Between Life and Death

- Live Deaths and Afterlives

- Bibliography

- Notes on Contributors