![]()

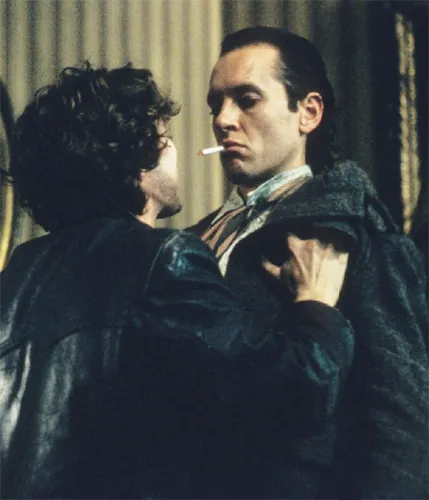

Left: Withnail and I, Handmade Films/The Kobal Collection.

COMEDY

Comedy is a significant, universal and enduring genre and British cinema has produced an extensive array of comedians, comic narratives and comic modes. While some examples, most notably the Ealing comedies, have become emblematic of British culture, defining distinctly national forms of comedy can be problematic, as Geoff King and Andy Medhurst have shown (King 2002 and Medhurst 2007). However, the disruptive potential of comedy, whether in the refined style of Ealing classics or the carnivalesque release of the Carry On films, seems especially powerful in a culture like Britain’s that seems to cleave to hierarchy, decorum and order. Hence the delight in the ways in which the lascivious George Formby, Alistair Sim’s coy Miss Fritton, or the misanthropic Withnail challenge British norms of class, gender and propriety.

British comedy is reliable at the box-office: low-budget work can reap good domestic profits, and some high-concept vehicles, such as Bean (Mel Smith, 1997) can be internationally successful. Most British comedy is performer-led, showcasing established comedians and comic groups. While the influence of theatrical styles on British film comedy can be traced, for example, in Oscar Wilde adaptations, music hall, variety, radio and television have provided the main sources for film comedy performers and characters, from Gracie Fields to Simon Pegg. A century of British comics, from Charlie Chaplin to Sacha Baron Cohen, have also become Hollywood stars.

Early cinema embraced comedy with chases, transformations and what Tom Gunning (1995) has called ‘mischief gags’ – all key elements of British and international films. As artisanal output declined, individual performers and characters emerged more strongly. Fred Evans, for example, became a star in the WWI era, just as his childhood friend Chaplin emerged in America. Evans’ popular Pimple character featured in onscreen escapades that often parodied popular films and genres, as in Pimple’s Battle of Waterloo (Fred and Joe Evans, 1913) which burlesques the historical epic. Similarly, Betty Balfour, a leading comedy star of the 1920s, played the character of Squibs, a Cockney flower seller, in a series of films that mixed comedy and sentiment.

1930s’ comedy was dominated by two stars, George Formby and Gracie Fields, who represented notions of northern authenticity and cheer during the Depression era. Originally music hall performers, their films showcased their musical and comic skills equally. Formby moved between childlike innocence and the knowing innuendo of his songs, such as ‘With My Little Stick of Blackpool Rock’. While Fields shared Formby’s lovelorn quality, her persona was conciliatory and reassuring, as when she saves her cotton mill from closure in Sing As We Go (Basil Dean, 1934). Other popular performers of the period with music hall roots included Will Hay and Arthur Lucan, creator of Old Mother Riley. A more sophisticated, concert party ethos was represented in the work of Cicely Courtneidge, often partnered by her husband Jack Hulbert.

Ealing Comedy, which has become a touchstone for British film, emerged in the mid-1940s and continued to produce films for a decade. A commemorative plaque placed at the entrance of Ealing Studios on its closure in 1958 reads, ‘Here during a quarter of a century many films were made projecting Britain and the British character.’ Ealing comedies celebrated eccentric forms of rebellion or collective action, as in the gold bullion robbery masterminded by a timid bank clerk in The Lavender Hill Mob (Charles Crichton, 1951), or the Scottish islanders’ appropriation of shipwrecked alcohol in Whisky Galore! (Alexander Mackendrick, 1949). Responding to the anxieties of the post-war austerity era, Ealing films like Passport to Pimlico (Henry Cornelius, 1949) emphasized the value of community against the state, while others offered much darker views of society: in The Ladykillers (Alexander Mackendrick, 1955), for example, the group is monstrously venal. Alongside Ealing, the Boulting Brothers provided a rather jaundiced perspective on post-war society. Their series of satirical comedies began with Private’s Progress (John Boutling, 1956) and peaked with the cynical study of labour relations, I’m All Right Jack (John Boulting, 1959).

The 1950s, once considered a stagnant era for British cinema, now seems rich in comic talent. The comedian Norman Wisdom rose to stardom with Trouble in Store (John Paddy Carstairs, 1953), which introduced his inadvertently destructive ‘Gump’ character. There are parallels with Formby, but Wisdom employs greater pathos: he is more innocent than gormless and his songs, such as ‘Don’t Laugh At Me ‘Cos I’m a Fool’, are plaintive rather than lewd. In 1954, The Belles of St Trinian’s (Frank Launder) initiated the highly successful and classically British St Trinian’s series. Set in a disorderly girls’ boarding school, Alistair Sim’s drag performance as the headmistress, Miss Fritton, is only one disruptive element in films that suggest the anarchic power of femininity.

The supremacy of the Rank Organisation during the period encouraged the growth of the middle-class comedy. Genevieve (Henry Cornelius, 1953) mixed tradition and modernity in the romantic comedy story of two couples competing in the London to Brighton vintage car rally, with the chic and authoritative Kay Kendall emerging as a major comic talent in a period when most female characters were demure helpmeets (Geraghty, 2000:160–66). And the series of Doctor films starring Dirk Bogarde, such as Doctor in the House (Ralph Thomas, 1954), emphasizes bumptious middle-class life rather than the body humour of the hospital Carry On films.

The Carry On films were a dominant presence in the 1960s, producing 29 films between 1958 and 1978. With their emphasis on sexual innuendo and bodily functions, these cheaply-made, hugely popular films exemplify the best and worst of the British low comedy tradition. The early films, Carry on Sergeant (1958), Teacher (1959), Nurse (1959) and Cruising (1962), directed by Thomas and written by Norman Hudis, echo a post-war, sub-Ealing ethos of consensus, with a ramshackle group learning how to become responsible professionals. Talbot Rothwell’s scripts, from 1963 onwards, specialized in more riotous genre parodies including Cleo (1964), Spying (1964) and Screaming (1966). But the final films in the early 1970s made an uncertain return to contemporary settings.

Carry On is a world of workshy, henpecked men, shrewish wives, gormless and lusty youths and predatory women, where class and gender boundaries are loosely maintained. The appeal of the films lies partly in their ragged air. Parodic plots provide a familiar base and loosely-structured narrative on which to pin gags, slapstick and innuendo. A repertory of performers in standardized roles was also crucial to the films’ success. The comfortingly familiar Carry On team, led by comedian Sid James, made household names of Hattie Jacques, Bernard Bresslaw, Jim Dale, Joan Sims and Barbara Windsor. Kenneth Williams was a leading radio star when he joined Carry On, appearing in the cleverly camp series Round the Horne, and his involvement spans the entire output. Initially cast as a supercilious intellectual, Williams developed a conspiratorially camp persona that, alongside the fey Charles Hawtrey, contributed to Carry On’s strong queer dynamic.

As British society changed and became more liberal, the films tried – with varying degrees of success – to engage with contemporary issues such as trades union strikes (at Your Convenience, 1971) and even feminism (Girls, 1973...