- 170 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Engendering Interaction with Images

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction: See. Change.

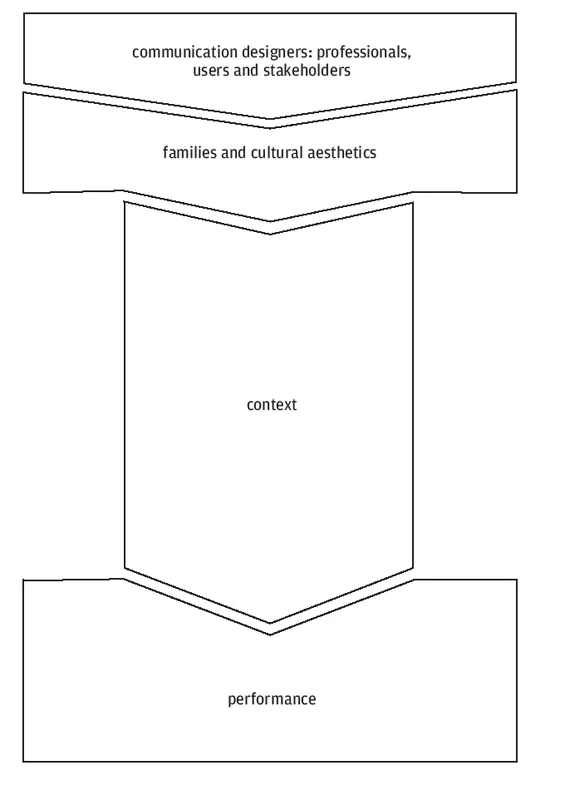

The word image comes from the eleventh-century Latin ‘imaginem’ which means picture, statue, idea, copy, and appearance.1 Most dictionaries today define it similarly—as both a verb and a noun with cross-disciplinary usage within mathematics, computer science, communication, art and physics. Engineering, the social sciences and other science disciplines use the word image as well. Consider scientific visualization (an emerging sub-discipline focused on the visual display of complex, technical information) and visual anthropology (a sub-discipline of anthropology that studies ethnographic images). Within interdisciplinary discourse, we can find perennial intellectual debates on what constitutes an image from disciplines like “literary criticism, art history, theology, and philosophy”2—all of which use images differently. Thus, art historian W.J.T. Mitchell appropriately visualizes an image as a family tree that branches out into a range of categories including graphic (from art history), optic (from physics), perceptual (from multiple disciplines), mental (from psychology and epistemology), and verbal (from literary criticism).3 In Mitchell’s family tree, each category branches out into a set of sub-categories that form a cohesive visual unit. His family tree visualization shows a kind of kinship between different image types that helps to facilitate understanding of what constitutes an image across disciplines. It also begins an important dialogue on the role of images as an evolving perceptual, cultural, technical and historical phenomenon within society. In Chapter 2, I leapfrog from two of Mitchell’s categories—optic and mental—into a broader re-categorization of images that reflects the influence of technology and globalization. My aim is to redefine image to be more inclusive of the rainbow of images in use today and explain how an image communicates meaning through a system that depends on stakeholders, familial characterization, cultural aesthetics, and context. In other words, an image exists as an ecosystem (see Figure 1) comprising:

| • | Different families, cultural aesthetics, and communication contexts. |

| • | A communication network that facilitates interaction between actors—that is, the professional communication designer, user and other stakeholders. |

| • | A performance component that warrants metrics for assessing communicative effectiveness. |

| • | A resilient nature that adapts to technological change and evolves. |

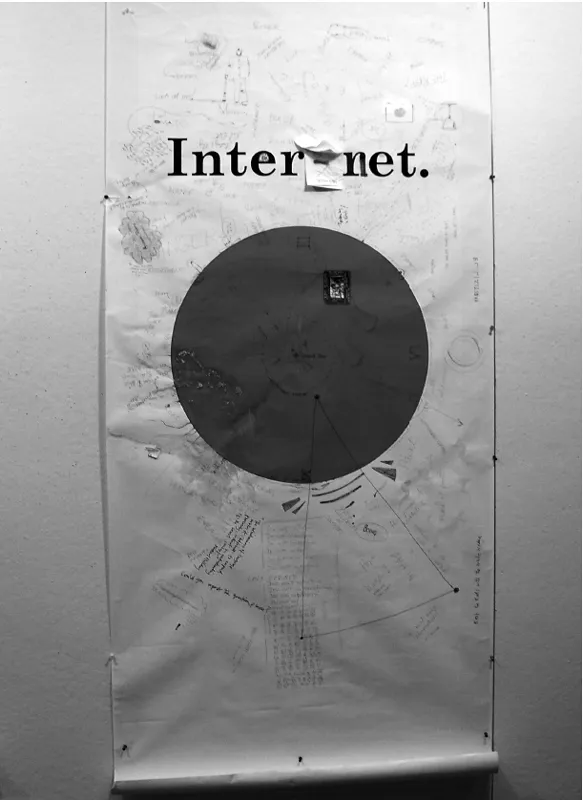

Figure 1: Image ecosystem depiction that shows resilience and ability to evolve represented by the stoic stance of a slab- serif letterform.

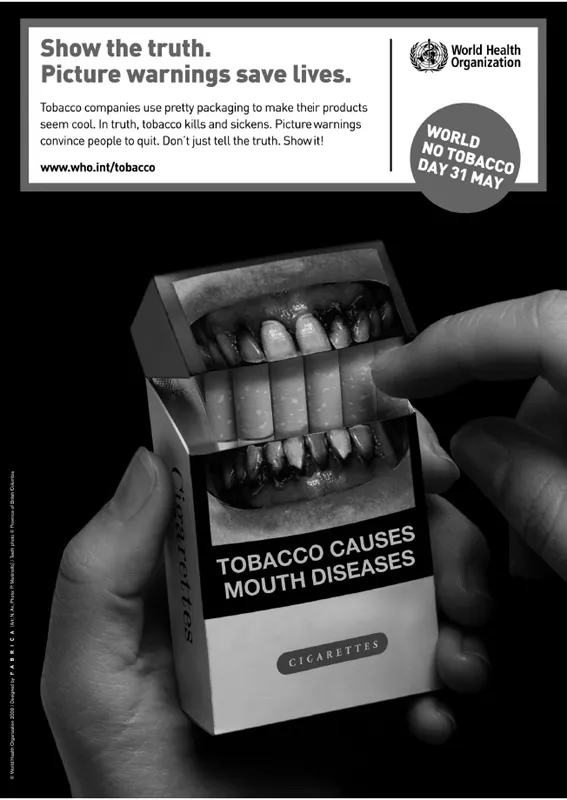

How an image ecosystem communicates meaning has been the subject of scholarly debate for many decades. Faigley et al.,4 for instance, believe that the act of communicating with images is similar to the rhetorical act of communicating with text. They essentially argue that an image is text. However, the opposite is more accurate: text is image. That is, text is a written or typeset group of words that comprise letters that are visual symbols with phonetic sounds associated with them. As Saussure describes it, the written word is a “graphic representation of language”5—an image. And, while we cannot reduce all images to text, many of the theories we use to analyse how text conveys meaning can also be used to analyse images. For instance, as the rhetorician moves (movere), instructs (docere), and delights (delectare),6 the communication designer also uses images to inform, entertain, or persuade the user to adopt or change a belief or behaviour. Consider the image in Figure 2 that aims to evoke a change in behaviour by showing the negative ramifications of smoking through the package design.

Figure 2: Show the Truth, World No Tobacco Day Campaign

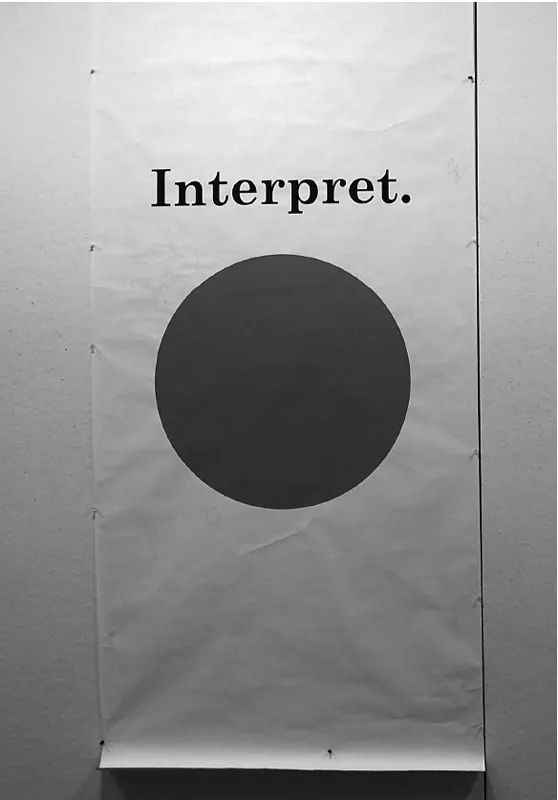

If we look specifically at twentieth-century, literary criticism we find a rich reservoir of interrelated and evolving perspectives on how images communicate meaning. Consider the image of a simple red circle. From a Saussurean perspective, this image is a sign comprising a signifier (its form as a red circle) and a signified (a concept or idea it represents) where the relationship between the signifier and the signified is an arbitrary one.7 The arbitrariness of the relationship between the signifier and the signified is most likely influenced by the culture of the user and communication context. As the late design historian Philip B. Meggs notes:

The interpretation of a sign is impacted by the context in which it is used, its relationships to other signs, and its environment.8

Thus, the basic image of a red circle can mean several different things depending on the culture of the user and the context in which it communicates to targeted users. For example, when printed on a white piece of cloth attached to a pole—placed at GPS coordinates 37° 34’ 0” North, 140° 59’ 0” East—a red circle might mean Japan (the country, the people, and their culture) to some; whereas, when painted on the external wall of a store in 1933 Charleston, South Carolina, the same red circle might mean “liquor sold here” to others.9 Thus, the red circle has two levels of communicative significance— one that is denotative (explicit, literal, and primary; the status of signifier) and another that is connotative (implicit, symbolic, and secondary; the status of signified). On a denotative level, the red circle is literally “a simple [red] shape…consisting of the set of points in a plane that are a given distance from a given point, the center.”10 However, on a connotative level, the red circle may symbolize other things like patriotism or even the end of prohibition. Cobley and Jansz argue that we recognize what a sign depicts (the denotative) before we decipher its cultural, social, or emotional meaning (the connotative).11 Thus, we recognize the red circle before we might interpret feelings of patriotism for Japan. However, “connotation depends on a reader’s knowledge…intelligible only if she has learned the signs.”12 That is, “signs can convey their message to only those individuals who have learned the sign or the sign system.”13 Communication designer Jorge Frascara notes:

Figure 3: Left: Image of a red circle underneath the imperative statement “Interpret.” Right: Same image as on left but with the addition of handwritten and hand-drawn, user interpretations of red circle.

At the level of connotation, the public participates more actively in the construction of meaning. The connoted message is more culture- dependent, and it is built as a combination of the designer’s concept and the target public’s experience.14

It is the emergence of the active role of users in the evolving study of images as signs that gives way naturally to rhetorician Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory of dialogism15 when defined as a “communicative interaction between a speaker [e.g. a communication designer] and a listener [e.g. a user or reader].”16 According to communication design educator Ann Tyler,17 the interaction between the communication designer and user ranges from passive spectatorship to dynamic participation where users either observe aesthetically-pleasing images without knowing the producer’s communication goals, interpret images without contributing to meaning, bring their own cultural beliefs that influence how they interpret the image, or become persuaded by the image to adopt a new belief. However, these definitions of active participation are limited. Tyler’s dynamic participation and Frascara’s notion of active participation during connotation refer to what takes place in the user’s mind, at a strictly connotative level. One of the exciting developments that have recently emerged through media is that user interaction is no longer restricted to the connotative dimensions. Today, users can determine denotative aspects such as the choice of skins for digital applications, fonts for browsers, other customization options like colour; even mashups and appropriation can transform the communicative experience into one of active user interaction. The question I ask is: What happens when users contribute actively—in a physical and intersensory way—to the co-construction of the image at the denotative and consequently connotative levels, and what are the ramifications of that interaction on the image’s communicative effectiveness? In addition to the denotative/connotative distinction (which some describe more as a continuum than a dichotomy), meaning also occurs within a continuum from intersensory to unisensory interaction. Images that facilitate active modes of interaction often engender intersensory experiences, whereas unisensory images typically facilitate a passive mode of interaction (think clickable web-based images versus non-clickable printed images). It is active modes of interaction that often yield greater communicative effectiveness because the user contributes actively to the image’s meaning.

While the ability to alter the denotative aspects has accelerated with the advent of digital media and technologies, we can see this phenomenon in print media as well. For example, at the CoDesign 2000 conference in England, I presented attendees with an image of a red circle with the imperative statement “Interpret.” typeset above it—as depicted on the left in Figure 3. A writing tool was visible and accessible to attendees of the conference. They were allowed to respond by writing their interpretation onto the image. The image on the right in Figure 3 shows their written interpretations of a red circle. One response that exemplifies the idea of co-construction of meaning can be clearly seen in one user’s modification of “Interpret” to spell “Inter-net” which changes what the overall image communicates. Thus, the questions then become: In which contexts do images that engage users actively communicate meaning more effectively? Can we use the idea of active mode of interaction to improve cultural resonance, impact on humanity and society, and visual appeal? The thesis I explore in this book is an affirmative response to these questions. I posit that images that facilitate active modes of interaction between the user and the image communicate meaning more effectively.

However, as tempting as it may be, I cannot claim that more interaction is always better. We are all familiar with interaction disasters like the ‘feature creep’ that puts more and more widgets of dubious value into our favourite computer applications; customization menus that hide crucial controls in a forest of trivial options; animated paper clips that annoy more than they instruct. Rather, these new modes of image interaction require a more thoughtful approach, in which designers are willing to gather data from users and treat designs more as testable hypotheses. This does not mean that we must reduce all assessment efforts to quantitative and qualitative analyses. Instead, we need a new partnership between the intuitive, artistic aspects of communication design and a willingness to listen to users and other stakeholders and help users to contribute their ideas to the communication design process.

This idea of active engagement is similar to Barthes’ concept of active (versus passive) readership, where the reader of a “writerly text”18 may be “called on to be in some sort the co-author of the score, completing it”19 or becoming “a producer of the text.”20 Whereas, with the opposite—“the readerly text”21— the reader becomes more of a spectator; and, “reading is nothing more than a referendum.”22 However, unlike Barthes’ passive and active reading which is limited to denotation and connotation, I purport that all images facilitate another kind of active or passive interaction in terms of their degree of intersensory interaction. Thus, images communicate meaning denotatively, connotatively, and also through intersensory experience between the image and its user. Then if we revisit the question of what constitutes an image today, we might say: an image is a technologically- rendered or natural visual depiction that communicates meaning through passive or active modes of interaction in order to communicate meaning. As a verb it means to create a visual depiction that communicates meaning through passive or active modes of interaction.

Assessing how well an image communicates meaning traditionally focuses on what Tyler describes as a “presentation that only emphasizes the aesthetic sensibility of the individual designer and severs the [image] from its relationship with the intended audience.”23 Instead, what we should ask of images are questions like: What are the communication goals? Who is the targeted user? Which metrics can we use to evaluate whether or not the given image outcome relays meaning effectively? In the case of the red circle image in Figure 3, is it more communicatively effective because it actively engages the user in the interpretation of the image? One could conclude that, based on the relatively high quantity of hand-written and— drawn responses recorded on the image as well as the “Best Poster Paper” award conferred by the conference’s steering committee after it earned the majority vote from the conference attendees. Yet another approach to determine communication effectiveness might be to assess the image against the set of metrics in Chapter 3 that holistically evaluates the image’s cultural resonance, impact on humanity and the environment, and visual appeal.

Two phenomena have simultaneously broadened the reach of images and impacted the potential o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Image Credits

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- PART I: ECOSYSTEM

- Chapter 2: Image

- Chapter 3: Effectiveness

- Chapter 4: Interaction

- PART II: ENGENDERING INTERACTION WITH IMAGES

- Chapter 5: Collaborative design through active interaction

- Chapter 6: Collaborative design through active interaction with a dynamic image

- Chapter 7: Computer mediated collaborative design of a static image

- Acronym Glossary

- Notes

- Index

- Colophon

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Engendering Interaction with Images by Audrey G. Bennett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.